I like a newspaper I can hold in my hands because sometimes the stories across the folds can talk to one another in ways that never seems to happen on a screen. That kind of exchange took place in my newspaper today.

For as long as I’ve been reading it, the Wall Street Journal has a funny, odd or just plain ridiculous story at the bottom of Page One. At some point, the Page One editor must have decided that stories like this are good antidotes to the calamities, logjams and shenanigans chronicled above. These daily stories always froth over to the last page of the “news” where they brush up against the beginnings of the “commentary” section on the other side of fold. It’s here that strangely compatible bedfellows sometimes meet.

Page One’s dollop of the day today was about a long-standing West Point tradition celebrating the graduating cadet, who by academic and other standards, finishes dead last in his class each year. Because of some “informal” information sharing, everyone but The Goat knows who he is on the big day, and when his name is called out from the graduating roster, the cadets erupt into the loudest cheer of the day.

There are two kinds of Goats, according to a disappointingly dry piece in a publication called Failure Magazine. There are cadets who labor through the muck to the bitter end, and those who take the experience just seriously enough to fall inebriatedly over the finish line. Of course, several of the Good Time Goats were actually pretty smart and went on to make history (Generals Custer and Pickett, for example). Several middling cadets did pretty well too. (Eisenhower reportedly said: “If anybody saw signs of greatness in me while at West Point they kept it to themselves.”) But it’s the ones who always struggled to do their best, while barely making it to the end, who are the real heroes of the story.

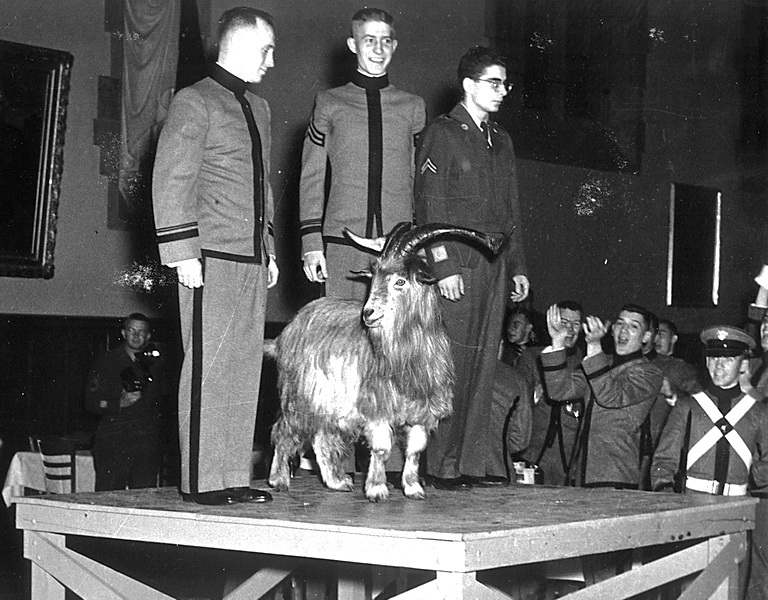

Unclear whether to be embarrassed or proud of their accomplishment, most of these Goats eventually seem to settle into being good sports about it. For example: “In my class, no one else can say that they’re the Goat and no one else can say that they’re part of this special lineage that dates back so far,” said good sport Roberto Becarra, Jr. in 2007. Somewhat earlier, the bespeckled Goat (below) seems to have had a similar reaction.

When asked about these persevering Goats by the Journal reporter, James S. Robbins said:

The tradition of the Goat is important because it kind of encapsulates that American spirit of—yeah, you’re going to have the top and they’re going to get recognized and they’re going to get stars by their names and all that other stuff. But, you know what? The guys further down, they have their chance too, and they can succeed too and it’s important to recognize them.

While his insight might have been more penetrating had he been a psychologist or meteorologist instead of an historian, Robbins’ remarks did manage to counterpoint similar observations about the value of “keeping your head up” and “putting one foot in front of the other” on the facing page of the paper, where a Journal writer reviews a new book by Nassim Nicholas Taleb called Antifragile.

Taleb’s singular perspective is that theories follow practice instead of the reverse. It’s not “the Soviet/Harvard notion that birds fly because we lecture them how to.” We learn by doing it first, and make up the theories that contain all of our how-to-do-it wisdom later on. It is, as the reviewer notes, “a startling [chicken v. egg] insight,” because what Taleb’s debunking allows is a flat-out celebration of the creativity involved in doggedly keeping at it. The many virtues of trial and error.

Taleb makes up the word “antifragile” to mean not only hardy, but also something that has been improved through repeated failures, becoming more resilient in the process. From this perspective, the persevering Goats are not just plodders: more than a few of them embody the adaptation that is at the beating heart of natural selection. As Taleb’s reviewer notes:

If trial and error is creative, then we should treat failed entrepreneurs with the reverence that we reserve for fallen soldiers.

This is why experience is the best teacher. It’s why “A” students who master the theory often work for the “B” and “C” students who rightly suspect that the magic lies elsewhere. It’s why rigidity and too much seriousness is always a bad idea. And it’s why the loudest cheer really should go to somebody who has not only failed most prominently, but also has the spirit to get up and keep trying.

Not that it’s always so easy.

[…] & error is what made some of the Goats such an inspiration (Just Plain Funny #2). They kept at it, got it well enough, grabbed the finish line, and were (I think) a lot better […]