This week, the ironies were hard to miss.

At exactly the same time that our president was yammering on about how Russia and Ukraine were “boys being boys” and still needed to fight it out before his peacemaking skills could save the day, he and “the world’s richest man” were devolving into their own dogfight, although in that instance it was harder to discern who’d be saving the day once the pair of them had exhausted themselves.

What this special military operation and schoolyard altercation superficially had in common were the assumptions that “this is just what boys do to one another when their emotions get the better of them,” that they’ll stop beating up on one another eventually, and that such periodic carnage is a pre-requisite for finally moving on.

In the dog-eat-dog world of Putin, Trump and Musk, that behavioral analysis crowded out other glosses on what’s really going on here. After Trump handed us this primer on masculine behavior, it was a further irony that Nate Silver (best known as the New York Times polling guru) gave us his own psychological insights about the boys & men who delivered the 2024 election to Trump and (more importantly) what the Democrats need to understand about this cohort going forward if they’re to have any chance of winning future elections,

Silver wants answers—and I do too—because any resistance to our Family Strongman is likely to fail as long as boys & men continue to view his alternatives more negatively. With Silver providing the statistical support, we’re finally able to probe deeper than the usual knee-jerk reactions to what everyone’s witnessed about “boys will be boys” this week.

Voters who happen to be boys or men are more likely than progressive critics to see that some quantum of aggressive risk-taking is just part of the male package, “a fact of life” instead of a deplorable choice. Because too many Democrats fail to accept boys & men “for who they are,” the party of Biden, Obama and Clinton has become more openly hostile to what it views as the “toxic” hot-wiring of half of the electorate.

So how deep is this problem and how should the Democrats reconstitute themselves to deal with it?

Before we get to Silver’s numbers (along with his and other’s interpretation of them), it’s probably worth recalling my post from February, “Too Many Boys & Men Are Failing to Launch,”where author Richard Reeves also approached the biases of today’s Democratic Party pretty directly:

“There was not really an alternative [to the Trump-Musk view of masculinity] put in front of them….In the final stages of the campaign, young men were being urged to vote for the Democrats if they love the women in their lives [which was essentially a pro-Choice argument], and that’s not good enough.

“It’s not to say that we don’t care about the other people in our lives, but you are essentially asking men to vote for Democrats because the Democrats stand for women. Well, that’s a flawed political strategy.”

But where Reeves flags part of the problem, Silver sarcastically observes that you can grasp the extent of the disconnect “by, y’know, actually looking at the polling data instead of relying on the stereotypes that Villagers [his name for Progressives] have about young men.”

At this point, I should probably repeat a prior disclaimer: that advocating for boys & men shouldn’t come at the expense of girls & women. There is no good reason that each of the sexes can’t thrive in a political context and in every other corner of American life. Unfortunately, advocacy for boys & men sometimes triggers misogynist resentments that are as unhelpful as blanket charges of toxicity.

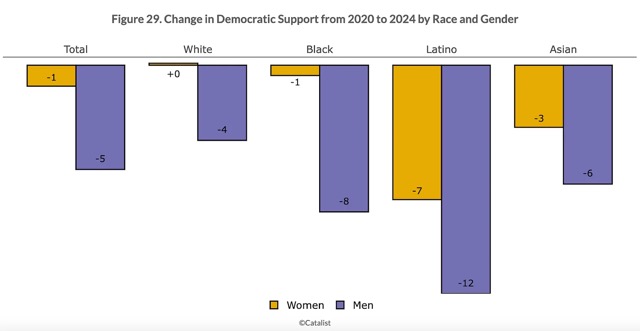

So what’s really happening here? Silver relies on polling for the starting point of his analysis: that in the 2024 election, “essentially all of the decline that Harris experienced relative to Biden [in 2020] came from boys & men.”

It’s not that all boys & men rejected the Democratic candidate, just enough of them for Harris to lose the election. (And because none of the observations here have the precision of science, it is likely that at least some of Harris’s rejecters could abide neither a woman nor a black woman as their candidate.) But Silver argues there are two “mistakes”—involving the “personality traits” of boys & men—that also account for the sharp decline in this cohort’s support for Democrats.

Mistake #1 has Democrats “missing that young men take a more risk-on view of the economy.” Turned-off by a nanny-state with expensive safety nets for every conceivable limitation or burden, Silver argues that many boys & men see Democrats “as what in the poker world we’d call ‘nits’: neurotic, risk-adverse, sticklers for the rules, always up in everyone’s business.” In other words, many boys & men prefer self-reliance to systemic excuses; fewer rules and regulations instead of more of them; and having their governors leave them alone instead of constantly trying to improve things for them.

And when it comes to risk in particular, Silver writes:

In my research, I found that risk tolerance is something of an understudied personality trait, but the two truisms are that men generally have a higher risk tolerance than women and younger people are more risk-tolerant than older ones….

The messages Democrats are proposing tend to emphasize security — minimizing downside risk — above the opportunity to compete and maximizing upside outcomes…So when [the progressive] Villagers design messages to win back these young men, I suspect a lot will be lost in translation. Just being more chill, being wary of progressive-coded messages that seem to impede competition and risk-taking, and recognizing that gender is a touchier subject than race, could be better than hiring a bunch of influencers who are trying to start a political conversation these men aren’t really seeking out.

This recommendation goes some way towards explaining why so many boys & men preferred a “successful businessman” (Trump) or “outside-the-box entrepreneur (Musk) to someone like Harris, whose only jobs have been in government. Of course, whether enough of those trying to steer the Democratic Party in more productive directions can actually see these kinds of solutions through their stereotypes about boys & men remains unclear.

Mistake #2 that Democrats have been making delves even deeper into the personality traits that differentiate boys & men from girls & women, once again with supporting data that Silver gathered.

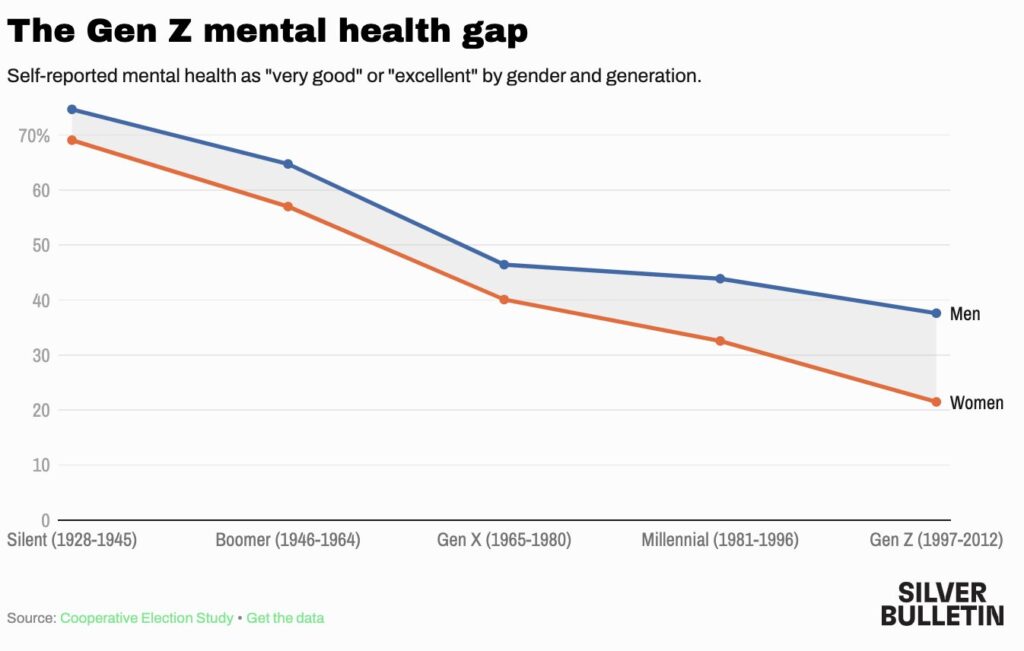

In news stories that have appeared in recent years, there has been the strong suggestion that boys & men are having as many mental health problems as girls & women due to social-media and smart-phone addictions. Silver (and his data) along with a related article which is delightfully entitled “According to Study, Young Men Are Not Mentally Ill Enough to Vote Democrat,” take issue with that premise.

Silver writes:

[T]he young men that Democrats have trouble with aren’t necessarily the ones who have been captured by the conservative ‘manosphere’ or who are looking for a helping hand. Rather, it’s those who report relatively high mental health and see Democrats as being too neurotic and perhaps constraining their opportunity to compete and reap the rewards of their work.

The underlying data points also tell him that “in the United States, higher self-reported mental health is strongly correlated with holding conservative political views.” [emphasis mine]

Silver graphs a long-standing mental health gap between boys & men, on the one hand, girls and women, on the other, over the past hundred years—with the gap widening measurably when you get to Milennials and Gen Z.

And on the correlation between being mentally healthy and having conservative views, Silver looked at the entire population regardless of sex.

The companion commentary with the provocative title is from OutKick.com, a sports, news, and entertainment website known for its “in depth coverage” on a range of topics. The site has a conservative bent and was recently acquired by Fox News. While I view Silver (and he seems to view himself) as “left-leaning,” there is no sunlight between conservative OutKick and Silver on the Democrat’s boys & men quandary.

Here’s the closing (free) advice from OutKick for Democrats who (given the condescending heights they inhabit) the site frankly doubts they’ll be able take:

“The Democrats don’t need to lean into fake machoism to regain support among young men. However, the party does need to pivot–dramatically.

“One idea: stop telling white straight young men that they are privileged and must atone for it. Stop trying to convince them to move out of the way for women, gay men, and trans people because it’s their turn.

“There are no turns in a meritocracy.

“Most importantly, stop trying to shame men for being men…

“A good rule of thumb: if your candidate is too self-important and beta to sit down with… Joe Rogan, don’t expect to perform well with Gen Z men.

“In other words, don’t expect the Democrat Party to address its disconnect with young men by 2028. Just look at the list of early Democratic frontrunners—from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to Kamala Harris, from Gavin Newsom to Pete Buttigieg.

“Not exactly a quartet of people who young guys would want to sit and have a chat with, now is it?”

+ + +

Two parting notes before turning to the news stories that seemed most pertinent to being a good citizen this week:

There was a well-reported essay in last weekend’s Wall Street Journal about how boys & young men are discovering their roles and responsibilities as future providers, husbands and fathers in church-run community programs. I recommend “A Church’s Campaign to Teach Lost Boys How to Be Men.”

Finally, the image up top, which I call “Age of Kings,” was seen plastered on a Philadelphia street sign this week and posted on IG @streetsdept.

+ + +

This week’s links and images about how our Family Strongman is altering the checks and balances we use to govern ourselves begins with the little-known-until-recently IT company and government contractor called Palantir.

Among other things, Palantir products are data gatherers/organizers and threat-assessment tools. In recent days, the company has been accused by the New York Times and others of invading citizen privacy given the ways that its tools are being used by the current administration. My view: the reporting has been heavy on foreboding and light on facts thus far, but given Trump’s penchant for pursing enemies and the Supreme Court’s ruling this week that DOGE can have access to the Social Security Administration’s “non-anonymized” personal information (some say, to “curate detailed portraits of Americans based on government data”), the current administration’s use or misuse of Palantir’s tools should be monitored closely by all who take their Constitutional protections seriously.

1. You can gain some of the basic information about Palantir’s expanded work in this May 30 article in the New York Times(“Trump Taps Palantir to Compile Data on Americans”) along with this multi-part tweet on X, posted by a former Palantir executive who argues that some of the Times reporting was either misleading or just plain wrong (Wendy Anderson’s rebuttal on X).

2. “Law Firms that Appeased Trump-and Angered Their Clients,” a lengthy article in the Wall Street Journal this week, chronicles the backlash to national law firms that struck deals with the president after he targeted them with executive orders because of cases they had brought against him, his administration or policies he favors in the past.

To date, nine major law firms have struck deals, while four others chose to fight. Regarding the fighters, courts have ruled that the executive orders involving three of the firms are “unconstitutional retaliation,” while a temporary order blocking Trump’s executive action has been entered on behalf of the fourth firm.

Clients are also pulling work from the firms that caved under pressure, “expressing concern” about whether these firms will be tough enough to stand up for them against adversaries “if they weren’t willing to stand up for themselves against Trump.” Tremendously lucrative books of business are involved.

Significantly, the article also reported that:

Trump remains interested in the [targeting] orders, and deputy White House chief of staff Stephen Miller and his allies want to keep the threats of more executive orders on the table because they think it dissuades the best lawyers from representing critics of the administration.

3. “Judges Weigh Taking Control of Their Own Security Amid Threats” also appeared in the Journal this week, as threats to judges who have entered orders against the administration have continued to be made by the president, by his appointees and by his MAGA supporters.

Starting in April, some judges and their relatives received unsolicited pizza deliveries in the name of Daniel Anderl, the deceased son of U.S. District Judge Esther Salas. Anderl was shot dead in 2020 at his parents’ home by a disgruntled litigant.

Judges described being fearful because anonymous people who threatened violence knew where they and their families live.

“One judge said the harassment caused them to weigh the integrity of their rulings against the safety of their family [members].”

As I said here a few weeks ago,, we know we are losing our democracy when citizens (including judges) start modifying their standard practices out of fear of retaliation by the president or his henchmen.

(Of course, Trump has already effectively compromised the independence of dozens of Republicans in Congress—the second of three “co-equal” branches of government—by threatening “to primary them” in upcoming elections if they dare to cross him.)

4. In Trump’s first five months in office, everyone watching has witnessed the on-again/off-again tariffs that turned an improving American economy into a skittish one; his appointment of incompetent (Pete Hegseth) and alarming (RFK Jr,) individuals to run significant arms of the government; our country’s failure to adequately support Ukraine and a world order that opposes one country’s invasion of another; family and personal use of the Oval Office for enrichment on an unprecedented scale; and this week, Trump’s social media hissy-fit exchanges with Musk.

Given the regime’s performance to date, how is America being viewed these days from outside our borders? How are adversaries like Russia, North Korea and China assessing Trump 2.0? I’m embarrassed to admit that the satirical on-line news blast The Onion may once again have gotten it exactly right.

This post was adapted from my June 8, 2025 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes I post the content from one of them here, in lightly edited form. You can subscribe by leaving your email address in the column to the right.