As I write this, tens of thousands of people are waiting in line in London “to pay their respects” to the Queen. This is no casual choice, since the viewing-line stretches for miles and it could take you a day to reach your goal, which is a walking glimpse (and perhaps a bow of the head or bended knee) before her standard-draped coffin in Westminster Hall.

If you were lucky enough yesterday, the trajectory of your arrival might also have coincided with the brief visit by the Queen’s children (and new King) who were there paying homage to her memory at the compass points of her resting place. But the lines that kept forming outside didn’t need the glimpse of any living royal.

Some asked why so many would wait so long to just walk by.

In my own wondering, I learned that since at least World War II, the Brits have developed a curmudgeonly fondness for standing, waiting for something and ambling towards “whatever it is” with others, chatting and complaining as they go. In the War years, the quest was for rations; today, it’s for a different kind of sustenance.

The British are known for their love of getting in line, which in Britain has long been called a ‘queue,’ from the French word for tail. It was once said ‘an Englishman, even if he is alone, forms an orderly queue of one.’

Despite the solitary joke, joining a queue is essentially a group experience, the participants joined by a common desire about what they’re likely to find at the end along the way.

Jenny Muskat, a middle-age woman from London, emerged from Westminster Hall late Thursday and said it took her ‘only’ six-and-a-half hours of waiting. She said she had been unsure earlier in the day about joining the line, but was happy she did after making fast friends with others in the queue. ‘We spent all these hours together, we laughed together, we just now cried together, and it was beautiful,’ she said.

What most of these Brits are doing—and it seems incomprehensible to some—is investing a great deal of time and effort to express their collective respect. They’re saying by this stupendous outpouring: “Thank you. As our Queen, you have given me, given all of us a great deal. In fact, you’ve given us a view of our best selves: Steady. Gracious. Tireless. Of our wry sense of humor. Thank you for being there, for making the rest of us look this good for all these years.”

Masses of people “paying their respect” seems almost unthinkable at a time when irony and cynicism make short work out of anything that’s cherished. People on social media were incredulous that anyone in their right mind would wait for that many hours to walk past a box with a body in it. If a national figure with millions of followers like Donald Trump (certainly a ”comparable” in terms of devotion) were to die tomorrow, the crowds would surely come out, but their gathering would be more of a political act, a kind of middle finger to everyone who didn’t come out, instead of a mass demonstration of respect for public virtues and the personal impacts of their mirrored glory.

The Queen’s Queue

To me, the Magic of the Queen derived from the fact that she was always, throughout her very long life, a kind of cipher. We knew what she wanted us to know about her, and almost nothing more—those virtues again, like steadfastness, self-restraint and even nobility while she was greeting “her people” and accepting their hellos and flowers in her “walkabouts” at another town hall or soccer field.

Because the Queen was a kind of screen, her subjects and other admirers could project what they wanted onto her—a sense of majesty or a quintessential Britishness—and see such qualities reflected back upon them. Her fans are grateful today, eager to express their thanks and respect, because this idealized Queen made these “commoners” feel better about the parts of her that they see in themselves, and that at a time when almost nothing else in modern life does.

The closest that Americans come to this kind of “give and take” with popular figures tend to involve individuals with two qualities that are very different from those that the Queen projected and then returned by way of “reflected glory.” Our idealized figures are usually both “self-made” and “very rich.” The clearest example I can think of is Steve Jobs, who turned his particular mirror back on the rest of us by encouraging the dream that we could also transform the world (and become fabulously rich in the process) by having an idea and a garage in which to realize it. Interestingly, some of Jobs’ unshakable aura may also have come from his timing. In the years after his passing, social media’s cynicism and irony have done a better job of rightsizing his successors (like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos) so that their reflected glories are much less desirable to see in ourselves.

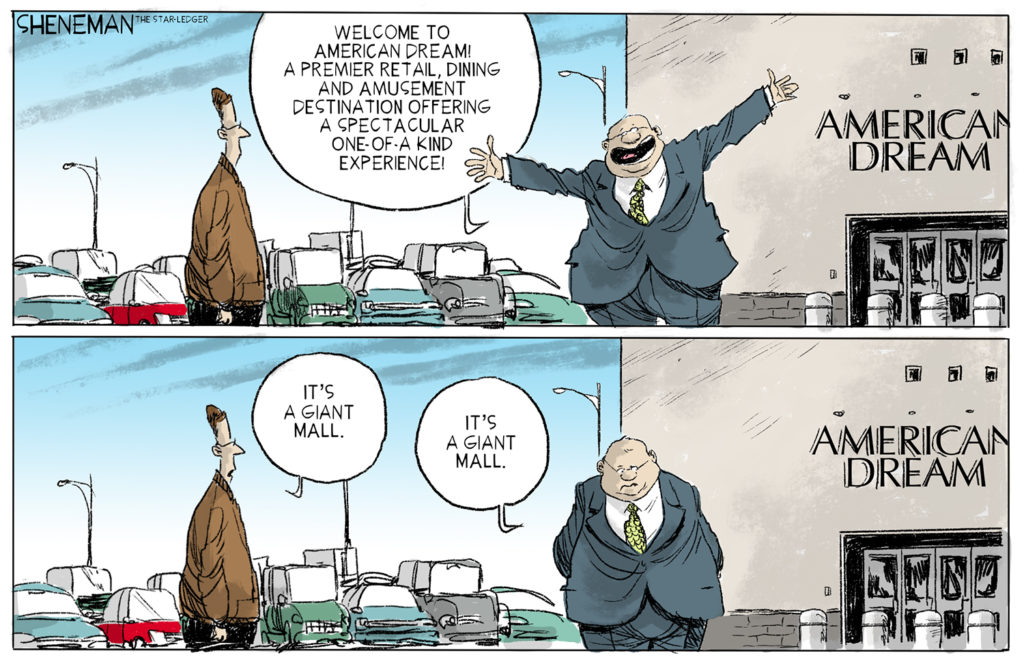

Instead these days, most of us have to project our plans about “making ourselves” and “becoming rich” onto a faceless American Dream, while hoping that what gets reflected back encourages our self-sacrifice, inventiveness, hard work and everyday desire to give our children better lives than we’ve had. Unfortunately, while millions continue to believe in that Dream, its promises are no longer encouraging most of us to work harder to achieve it. Instead, those workers who are paying attention in the lower 4/5ths of our economy feel stifled, stuck, betrayed, undermined and “quietly quitting” instead of having their upward mobility encouraged and advanced.

I say “those who are paying attention” because the “tradeoffs” of a top-down, government-managed economy (from the more entrepreneurial one that we had until the 1970s) were not only greater “fairness to all” (without regard to individual talent or effort), but also more material well-being (that is, more stuff) so that hopefully no one would feel quite so badly about the loss of an economic upside, and well-oiled corporations could reap more profits by satisfying our consuming desires.

Having this glut of stuff, along with the distractions of entertainment and social media—its full-bore anesthetizing effects as the years spooled on—are what Aldus Huxley forecast in “Brave New World Revisited,” written in 1932. In a prior post called Whose Future Should We Fear Most (which contrasted George Orwell’s and Huxley’s forecasts through today), I tried to capture the context for mass sedation that Huxley’s book so accurately anticipated.

In our era of 24/7 entertainment ‘on demand,’ of non-stop drama from our ‘news’ outlets, and of a constant barrage of social media updates, none of us ever has to pay much attention to what is happening in the so-called “real world” or the roles we should be playing in it. There is always a new ‘prompt’ from our phones, watches or “smart” speakers to provide us with a refuge from reality. The soma of near constant screen distraction and ‘the internet of things’ has also become a fixture of our daily lives in the four score years since Brave New World was published.

Too many who are no longer animated by the American Dream or disappointed by its promises have also been reduced to passivity by these diversions. They simply can’t be bothered to muster a justifiable sense of outrage before Netflix or YouTube suggests the next thing for them to watch.

But as inflation bites and more data gets mustered, it’s amazing to me that anyone “who’s not already rich or totally checked out” can avoid a sense of outrage and its class-driven political upheavals.

In a post from a couple of weeks back called The Great Resignation is an Exercise in Frustration and Futility I cited data suggesting that government management of the economy has caused the middle, lower middle, and lowest economic classes to realize essentially the same income at the end of their working (or non-working) days due to government transfer payments. But these redistributions of wealth also stifle upward mobility. Mass quitting followed by a frantic search for “better lives via better jobs” is not only a fool’s errand but also an invitation to deeper resentments against “capitalism” and “the American way of life.” It embodies the reality that most Americans these days feel stuck on their rungs of the economic ladder.

The effective death-knell for upward mobility may be saddest for previously disadvantaged people who have struggled and saved and sacrificed so that they could reach the middle classes only to find that they’re still experiencing economic anxiety over the costs of health care, education, a comfortable retirement or an unexpected emergency. It’s hard working rural or immigrant whites, urban Blacks, second or third generation Latinos who finally thought they’d broken through—were on their way to the Dream they’d projected their hopes upon—only to find that nothing but futility was reflecting back on them and making them feel like failures.

These white, brown and black Americans have sometimes directed their anger and bitterness towards the poorest among us who seem to be living as well as they are, or towards rich/oblivious Progressives at the top of the pile who can afford to have privileged views since they come at the expense of the remaining 80%. Instead of having someone to be thankful for (like the Queen) or to aspire to be like (such as Steve Jobs), Americans have been finding scapegoats for their rage like Black Lives Matter and its supporters or the Coastal Elites.

Notwithstanding where we find ourselves today (and in spite of all evidence to the contrary), the American Dream still encourages more hope than it can deliver on, and the country’s ire still hasn’t turned on the richest 20%, or the corporations that are also accruing a disproportionate share of the nation’s wealth.

Instead, there are enough folks in that lower 80% who still believe they can hit the economic jackpot that neither the “Occupy Wall Street” uprising of 2011 nor Bernie Sander’s democratic socialism movement in 2016 could enlist enough of the disgruntled masses. Moreover, while President Trump was directing his ire at poor and often minority protestors after the death of George Floyd, he and Congress enhanced the protections for the richest Americans and our most profitable corporations in the so-called Tax Reform Act of 2017. Like we were his game-show contestants, he continued to hock the Dream by telling us: Everyone in America can be a billionaire, just like me, once we rid ourselves of all these freeloaders.

Our increasingly empty Dream was about to lose even more of its hold on our imaginations during the pandemic. As a consequence, the pressure in the pressure cooker for the vast majority that finds it nearly impossible to better their circumstances will continue to build against the way that our elected leaders (both Democrat and Republican) have managed the American economy and designated its winners and losers for the past 50 years.

So where do we go from here?

Like an anti-addiction program, the first step is acknowledging the overwhelming evidence of the American Dream’s fragile state. In 2015, according to a study reported in Fast Company, the U.S. already ranked “among the lowest of all developed countries in terms of the potential for upward mobility, despite clinging to the mythology of Horatio Alger.” That article, called “The American Dream is Dead: Here’s Where It Went,” provided a breakdown of the developed countries where your chances of rising economically were the strongest.

1. Denmark

2. Norway

3. Finland

4. Canada

5. Australia

6. Sweden

7. New Zealand

8. Germany

9. Japan

10. Spain

America is simply not the Land of (Economic) Opportunity that it once was.

In my Great Resignation post, I joined Nobel-Prize-winning economist Edmund Phelps in waxing nostalgic for a more-entrepreneurial/ less-government-managed economy given the psychological and economic benefits that it brings to everyone who’s willing to work hard to get ahead. But Phelps didn’t provide much of a roadmap to recover our economic vitality when he wrote “Mass Flourishing.” On the other hand another economist, Oren Cass, has several ideas about boosting upward mobility for all American workers given the much-changed country that we’re living in today. (See my 2019 post A Winter of Work Needs More Color for an overview of Cass’s proposals, including incentivizing all of the country’s working families instead of subsidizing only a few of its most impoverished ones.)

In line with both Phelps’s and Cass’s thinking, we need to come to a more inclusive approach to the harms that follow when we stifle individual initiative and deprive a vast majority of the workerforce of its financial and psychological rewards.

A study that was reported out of Yale University this week argues that the lack of upward mobility early in life increases mortality rates in all young adults who confront it. While the emphasis in the study’s presentation was on groups that suffer the most (like young urban Blacks), it’s important to note the pernicious effects that are felt by every young person when they feel that they can’t improve their personal fortunes. A similar message came from studying pockets of white rural America that are dying from opioid abuse and suicide as chronicled in Angus Deaton’s and Anne Case’s ground-breaking “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism,” a book I briefly discussed here in another earlier post.

Many of the researchers and prognosticators who have confronted these problems have argued that “intergenerational wealth accumulation” is essential for upward economic mobility. In other words, how much your parents or even grandparents “had” and “left to you” may be as significant (if not more) to upward mobility than your personal work ethic. Some observers, like the author of this New York Magazine essay, clearly agree:

Without the safety net of accumulated family wealth, the children of self-made men and women can be ‘unmade’ in a hurry. With such wealth, by contrast, the trust-fund deadbeat’s child can follow her grandparents’ footsteps back through Harvard.

Thus, making America an exceptionally [upwardly] mobile society [again] will require a greater degree of income and wealth redistribution than most politicians would dare to suggest: To get more poor kids up the ‘ladder of opportunity’ we’re going to have to shorten the space between its rungs.

With my caveat that it’s not just “poor kids” but (more accurately) nearly everyone in the middle, lower middle and lowest classes, I am reluctant to argue that the same bipartisan government that nearly killed the American Dream should be given the mandate of “redistributing” the accumulated wealth at the top of our economy’s pyramid. But something needs to be done. If unlocking the nation’s sleeping economic vitality can’t be driven by wise leaders, than it is likely to be advanced by protests (and worse) on the streets.

Projecting my hopes for upward mobility onto the American Dream doesn’t have to become a reminder of my failures as a worker, it simply doesn’t. And allowing that kind of resentment to keep accruing is a dangerous thing.

Just as the Brits saw their reflected glory in their Queen and wanted to thank her for it, we can recover our reflected glory in the promises of that Dream—but we’ll have to want it as a country, almost more than we want anything else, given how hard that revitalization process is likely to be.

This post was adapted from my September 18, 2022 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes I post the content from one of them here. You can subscribe (and not miss any of them) by leaving your email address in the column to the right.