This season has been a harsh one for heroes. When you bring your values into your work, the example of others who have done so matters. So a season like this takes its toll.

Lance Armstrong was pulled down first by his win-at-any-cost rush for glory, and finally by his inability to reach beyond his grimace for a grace note. There’s a time for everything, and even Lance knows that it’s probably too late for him to say anything meaningful now. So instead this week he posted a picture of himself basking in the glow of all those yellow jerseys with the “passive/aggressive” caption: ““Back in Austin and just layin’ around…” One tweet (“Smug and deluded”) captures some of the reaction. For those of us who hoped for better, “Sad” would also be true.

Today it’s David Petraeus. His contrasting exit from the stage spoke of personal honor, the way a man should act when he’s disappointed himself and others. But in our need for role models, are we selfish to want something more in this instance too?

David Petraeus’ contributions in war were even more critical to this country’s interests than many of us realized given the failings of the generals he has had to push aside to bring a measure of competence to our expeditions in Iraq and Afghanistan. (In the just published The Generals, there appears to be American blood on the hands of far too many of Petraeus’ high-ranking colleagues.) So amidst a startling shortage of Pentagon talent, Petraeus stepped up for his country both on the battlefield and in the corridors of power.

But his extraordinary record of service and character also begs the question: Wasn’t there a better way to reach a productive future than for David Petraeus to withdraw from public life: a better way for him, for America, and for the rest of us?

There may be troubling facts around the Petraeus downfall that have not yet been made public. But given what we know today, I find myself wishing that his bosses had helped him find a way to not only take responsibility for his lapses of judgment but also to keep on making his unique contributions. Shouldn’t what has happened here be about more than one man’s conclusion that he let himself and his country down? Doesn’t David Petraeus seem to be the kind of man who could redeem whatever disgrace he feels today though more hard work on behalf of his country?

Heroes are human. Caught between heaven and earth, we handle their earthbound parts badly. Isn’t there a way to approach personal failings that includes, among its many options, a path that promises redemption after penance is done?

In 2008 Barrack Obama gave millions hope they could believe in, but four years later that hero has also been brought down to earth, tarnished by limitations that a slim majority found less troubling than the other guy’s. Obama could never have met the expectations his campaign created in 2008, or that many foisted upon him. But here, what troubles the most is that the president never took responsibility for what he promised but failed to do. He never said:

“I chose to take the helm when the ship was floundering. I wasn’t up to it then, and as a result I didn’t get us to clear water. You know it and I know it. But the buck stops here. I didn’t get it done. This is where I failed, and over here too. But this is also what I’ve learned from my mistakes, and I will struggle mightily not to make them again. Remind me when I’m not being bold enough. This is a big job. I need your help everyday—and God’s too—to find the courage we need to move forward from where we are.”

The president never said this to us. Instead his excuse seemed to be that his predecessor and his opponents were even smaller men. Maybe so, but you can’t move beyond your own failings until you own them. Unfortunately for him and for us, we’re all in an unproductive future with him this November: from the hero of 2008 to the lesser of two evils in 2012.

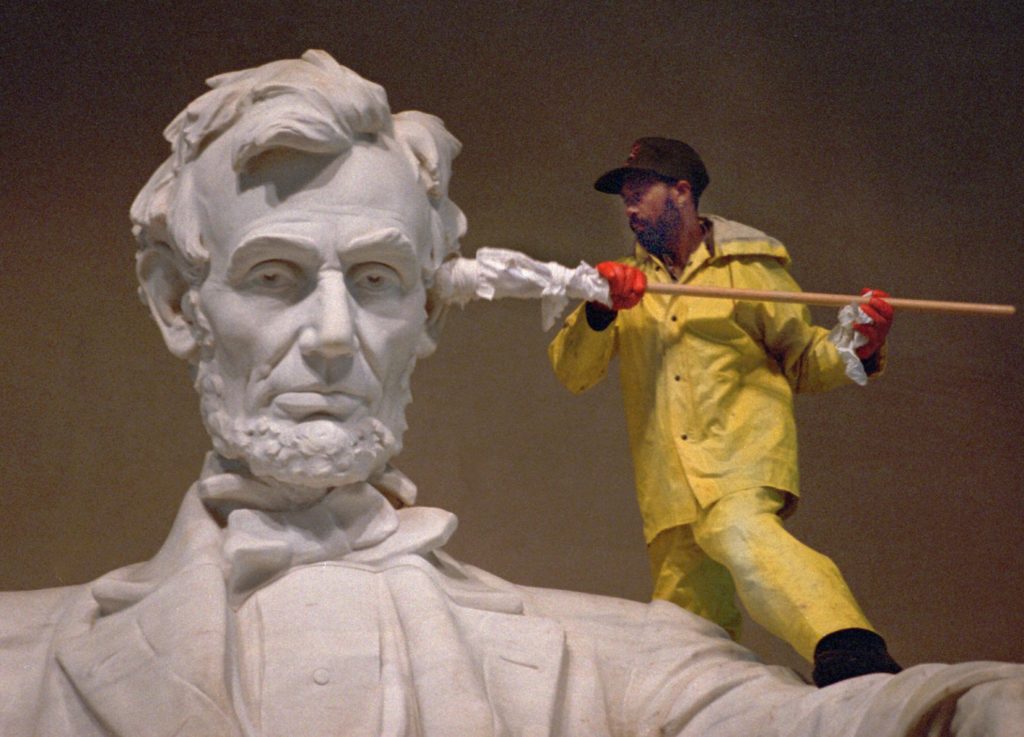

This week Lincoln comes to a movie screen nearby. Hollywood or Steven Speilberg or both may have seen an arc extending back from our first black president to the man who emancipated our slaves—and seen timeliness in this. But Lincoln’s life is timely now for a different reason. Almost alone among our American heroes, he was singularly focused on trying to describe how meaning could be found beyond the tragedy, sacrifice, and his own personal limitations.

The humility, sadness and struggle to reach a better future are all captured in Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. It was 1865. America was exhausted by an on-going war with bitter losses. Lincoln didn’t speak about having righteousness on his side. He got down into the moral mess of it, acknowledged while also struggling to look past the war’s unbearable costs to the forgiveness and rebuilding beyond. This is what he said.

Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes his aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered—that of neither has been answered fully.

. . . Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, ‘The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.

The pathway to something better that Lincoln spoke of in his time seems barely visible today.

It is grounded not in arrogance, but in humility and forgiveness.

Because we need to find the path again, it seems fitting that Lincoln will fill our fields of vision in what has been a harsh season for today’s heroes.

We have much to learn from him.