I’m thinking today about how quickly our lives seem to be moving thanks to all our devices, how much we’re adapting to this acceleration, and whether pulling ourselves onto the fast lane over and over again is a such a good thing.

Every day my internal clock collides with the digital clock that never sleeps. It’s like those days barreling down the entry ramp onto the highway with my poor Corolla struggling to accelerate fast enough. I always manage to inject myself into the stream of on-line traffic—but some days, just barely. It’s the torrent of email, video clips, photos, tweets, commentary, the latest news from North Korea. The speed and magnitude of incoming data is different than it was just a few years ago. What’s happening when we try to adjust to its demands?

We know from Daniel Coyle that your brain puts down tracks as you learn something for the first time through regular practice. The mastery of new tasks involves building new neurological highways with an “asphalt” in you brain called myelin. So when you are striving to get in sync with that digital clock day after day, where exactly are you headed? What are you becoming, what am I becoming with this new kind of machine-enhanced capability?

In terms of adaptation, researchers have just discovered microbes that have figured out how to live in a daunting environment called “the Challenger Deep.” It is the deepest part of the Mariana Trench, 6.8 miles below sea level, where all the biomaterials that haven’t already been consumed by the ocean of sea creatures above them eventually come to rest as food. It may have taken them millennia to adapt, but these feeding microbial creatures have shattered our presumptions about the temperatures, pressures, amount of light, and other factors that are necessary to sustain life.

Other deep dives have found jellyfish and tubeworms that have learned how to survive near underwater chimneys that boil the surrounding water to 635 degrees Fahrenheit. There is an unnerving sense that we too are beginning to adapt to the harsh environment of on-line all the time. The question is: at what cost?

In a recent article discussing his new book Present Shock, Douglas Rushkoff argues that we need to do a far better job of protecting ourselves as we jump between biological and digital time. Each of us already inhabits a body with intricate timing mechanisms that balance and adjust the rhythms of everyday life.

The body is based on hundreds, perhaps thousands, of different clocks, syncing to everything from the sun and moon to levels of violence and available water.

We can’t override the human clocks that maintain our equilibrium with the demands of today’s digital machine time without paying a price, but this is exactly what we are attempting to do.

[T]oo many of us aspire to be ‘on’ at any time and to treat the various portions of the day as mere artifacts of a more primitive culture—the way we look at seemingly archaic blue laws requiring stores to close at least one day a week. We want all access, all the time, to everything—and to match this intensity and availability ourselves: citizens of the virtual city that never sleeps.

Among other things, Rushkoff recommends that you “reclaim” your time, by making your digital devices serve your most basic human needs and not just struggle to keep up with them.

You usually need to know something’s wrong before you do something about it. Given the slow but steady acceleration of the digital onslaught in recent years, we are a bit like that frog in water that is gradually being brought to a boil and doesn’t know he’s cooked until it’s too late.

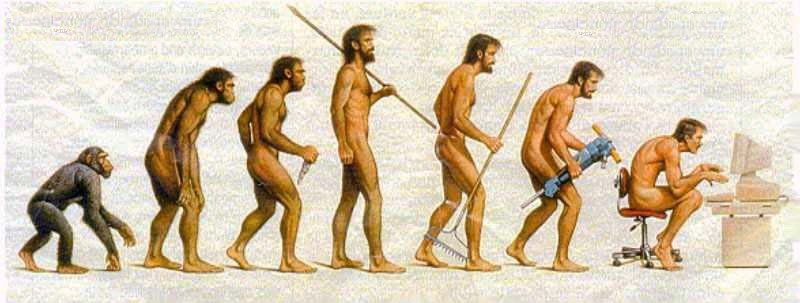

Of course our machines need to be tamed, even shut off now and then, so that it’s clear who’s in charge. On the other hand, it’s also true that every new use of technology tends to herald our next form.

Be careful out there.