Entrepreneur and investor Peter Theil was in Philadelphia on Monday sharing some of his contrarian views. One that he expanded upon at length affects innovation, education as well as our careers. Theil described it as “people acting in lemming-like ways.”

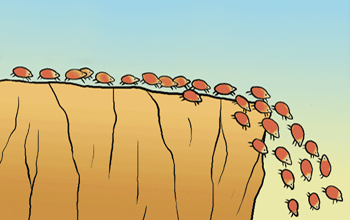

Lemmings are tiny hamster-like creatures that live near the Arctic Circle. Our image is of them frantically following one another to coastal cliffs in places like Scandinavia where they jump to their deaths in the frigid waters below. While we’re wrong to characterize lemming migration as mass suicide, there is no denying the herd-mentality that characterizes their movement from one place to another. It is the tendency we all have to jump off the same cliff that Theil was complaining about.

Lemmings are tiny hamster-like creatures that live near the Arctic Circle. Our image is of them frantically following one another to coastal cliffs in places like Scandinavia where they jump to their deaths in the frigid waters below. While we’re wrong to characterize lemming migration as mass suicide, there is no denying the herd-mentality that characterizes their movement from one place to another. It is the tendency we all have to jump off the same cliff that Theil was complaining about.

His impatience comes from wanting to nudge the world in a better direction if he thinks he can. As a result, Theil tends to be optimistic about innovation’s impact on the future and impatient with those who are failing to make the most of it. For example, on CNBC last week, he described Twitter as a “horribly mismanaged company” given its possibilities (“a lot of pot smoking going on there”), and took on Harvard Business School during the talk I attended, expressing his puzzlement about the games that are played there while accomplishing so little. Among entrepreneurs, his concern is that almost everyone is intent on “riding the last wave.”

“Big Data.” “The Cloud.” Whenever an idea gains some cache as the next big thing, everyone rushes in to contribute to what he calls “1 to n,” the adding of endless variations to something that has already been done. He called it the tendency “to ape” in the sense of imitating. Much harder but much better is to solve problems that no one else is thinking about in the way that you are. In other words, it is being able to go from Zero to One, which is also the title of a new book that captures his in-class discussions about entrepreneurship.

“Theil, who co-founded PayPal and was the first outside investor in Faceboook, is probably the most successful—and certainly the most interesting—venture capitalist in Silicon Valley,” notes a recent piece about him in the London Telegraph. Whatever people are doing at Twitter or Harvard Business School or in places where the topic is innovation, Theil gets exasperated whenever they seem more intent on climbing onto one another’s bandwagons than in thinking for themselves.

For some people, going to the best schools you can get into for four or more years after high school is just where the herd is headed. In Philadelphia, Theil admitted that he might still have gone to Stanford for college and then on to law school, but “would have thought about it a lot differently beforehand.” I know what he means. When a high school student has a more individualized sense of direction, why should she follow everyone else into higher education? So Theil started the 20-under-20 Fellowship Program, now in its fourth year, an admittedly rarified experiment in personal and professional development that I’ve talked about here before.

With a propensity to learn by doing, the fellows work with mentors that Theil has assembled in a 2 year, paid program that helps them to launch their own companies. When he was attacked by Larry Summers and others for what they viewed as his anti-college stance, Theil responded:

I didn’t think it would hit this sort of raw nerve. I mean, how fragile is the education system when 20 talented people leaving and doing something else is somehow enough to threaten it? My only claim is that not all talented people should go to college and not all talented people should do the exact same thing.

Which brings us to the work that we do. The career path that leads from the best possible kindergartens to the best possible colleges and professional schools is clearly the path that most young people want to be on. And they’re paying for the privilege with record student loans and crushing debt that hangs over them for years, if not decades. Is it worth it? Here too, the road less travelled—where you sit with yourself and figure out what you need and want from your work instead of simply following everyone else—has much to recommend it. Wherever it leads will not only make you happier, but also vastly improve the chances that your career could take you (along with the rest of us) from Zero to One.

During his Philadelphia whistle stop, Theil said that we all tend to underestimate what is different, those people and things “that don’t have a comparable.” When someone as different as Theil himself achieves conventional success, it allows him to trumpet “the unique perspective” in front of Philadelphia’s management class. For those of us who seek the courage to be different, he connected the personal benefits to the opportunities it can give us to change the world in often breathtaking ways.