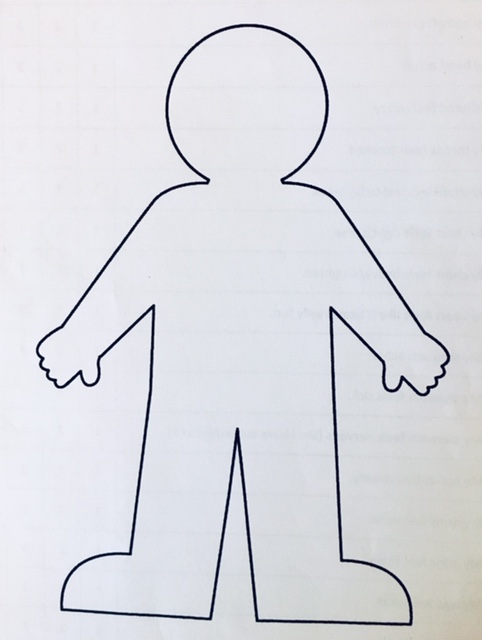

On Wednesday, I met with my group of 10 and 11-year olds who have recently lost parents or other caregivers. We gathered in small groups, huddling around a sheet that the staff provided. It was a simple page with the outline of a person on it. The kids’ aim was simple too. To write words associated with grief (like sad, angry, relieved, frustrated, lonely) on the part of the body where you experience those feelings most strongly. Surprisingly, one of the suggested words was “happy,” and B who was sitting next to me wrote it on one of her legs. I asked why and she said: “Because my mom is in a better place now and that makes me feel like dancing.”

The boys in the group were more interested than the girls in making the line drawings look like them. Superheroes are a big part of their worlds and larger-than-life always leaks into their self-image. Two boys insisted that they “couldn’t put their words in” until “they looked right.” One accomplished his personalizing simply by drawing the line of a cape behind his figure. One got busy coloring all the necessary details. Another took the relationship between the empty figure and what he feels about grief more literally. He drew in what looked like a central nervous system, a kind of “everywhere feeling” that was demonstrated by ganglia and synapses instead of words.

Presenting each kid with a physical container to fill up with their feelings did even more to stimulate conversation about what they’re feeling today. The kids are rarely this talkative about anything so heart-felt and personal.

One reason they come to the center is to spend time with other kids their age who have suffered the same kinds of loss. Just knowing you can talk about what you’ve gone through with somebody is its own relief, making this a refuge from all the other places where no one seems to know or be that interested. While their shared experience of death and its aftermath is what brings them together, most of the time few if any get around to talking about it. But today is different…

Maybe because it has them looking at their feelings, this line drawing launches a blizzard of conversation that’s so pent-up and overlapping it’s impossible to catch everything they’re are saying about themselves or to one another. Maybe because their focus was the grieving body, their conversation also got physical pretty fast.

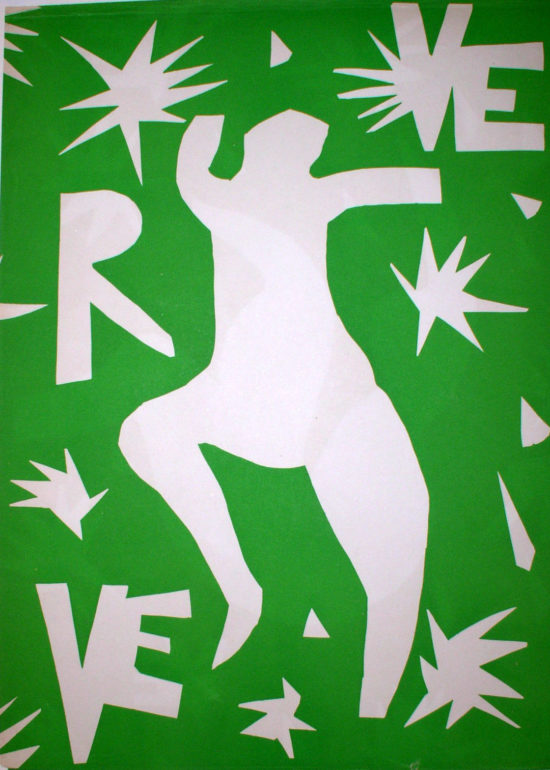

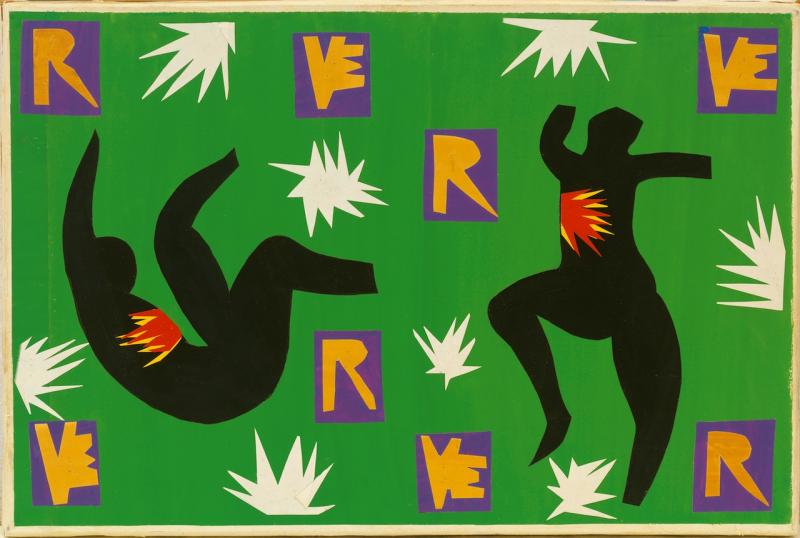

R told a story about his dream last night where his mom “appeared” in order to “warn” him about some threat I couldn’t catch because he’d already launched into a dance move from Fornite that H, who was sitting across from him in her hijab, immediately tried to show everybody too—R shamelessly insisting all the while that his moves were a lot better than her’s. The gusher of disclosures and the physicality that punctuated them brought us someplace that was even more elemental than the word choices around grief that we’d started with.

They all started talking about how “unsafe” and “afraid” they feel almost all the time, and it was not just because they’re trying to cope with a terrible loss in their lives. Every one of them felt that the outside world is elbowing itself into their lives and unsettling them to the core almost every single day.

They literally fell over one another talking about people they knew who had been shot, how the police never seemed to be around when you needed them, how much they worried about white police officers hurting black people, about conflict in the news, name-calling and blame, about how America’s leaders aren’t interested in protecting them either, and why “everybody’s fighting” makes them think that they need to lash out too to in order be heard.

Deaths in the family had put these kids one-step closer to everything else in the world that could harm them. Key insulation between them and the street was lost when their parents succumbed to illness and violence. It caused them to fear their conflict-ridden country. A dance move from Fortnite is all that tells them that they’ve fended off the threat, or at least the video game version of it.

The only time that I felt unsafe in America was in the wake of 9/11. Her mother and I protected Emily (a similar age to these kids at the time) from our anxiety, from the continuous media coverage, from our endless conversations about it, although I suppose it was hard to hide our alarm and what must have seemed like everyone else’s alarm from a child who was that perceptive. On Wednesday, these kids were describing that same kind of fear, with too few (if anyone) providing enough of a buffer between them and the anxiety that keeps “getting in” from “out there.”

In looking into their faces this week, I recalled that many of the most unequal and segregated places in America also happen to be the most “liberal” and “progressive”—and that Philadelphia where we meet, is even more so on both accounts. (See Richard Florida’s The New Urban Crisis.) Philadelphia tells the rest of the country that it’s a sanctuary city for immigrants and refuges, but seems like quite the opposite to kids like mine who were born here. It wasn’t bad politicians from somewhere else who created the mess in this city or have failed to clean it up, but you can’t tell that from the outward pointing anger of our politics.. These kids internalize some of that too.

This week, a new study was released with the finding that the second biggest predictor of a child’s life outcomes (after family income) was whether he or she came from a single parent household. The study findings were profiled in the New York Times, and by using the study’s toolbox you can key into neighborhood maps across America to predict the likely outcome for a child who is born there. The study’s authors collected data points from people born in the early 1980s and followed them into their 30s. In an interesting coincidence, the Time’s profile begins with a map that includes the East Falls neighborhood where I live and meet with my kids after school. Of course, some of them would be lucky to have even a single parent in their lives.

Vulnerable kids are also impacted by the fear and anxiety that raises their stress levels. A different kind of long-range study (this time in genetics) has been finding that a child’s environment not only causes certain genes to be expressed while others remain dormant, but can also change how the expressed genes work.

For example, these researchers have discovered that high levels of personal stress actually alter the genes that help regulate our responses to environmental pressures. Study participants who were abused or neglected as children were found to have different cells around this stress-regulating gene than children who were more protected and nurtured. In other words, stress changed these kids ability to respond to the world around them at a cellular level. (Some of those findings are summarized here.) Related research has been focusing on whether altered genes in stressed-out children can, in turn, be passed on to their own children. At the very least, damage from the stress of “what’s happening around us” can cause lasting if not permanent bodily harm.

This week, as I sat with my kids and listened to their fears, I couldn’t help but think back to my feelings and Emily’s after 9/11 and about how the two of us would feel about America today if we could both be that much younger again. The fearful kids who danced with false bravado on Wednesday were all born a decade ago in the wake of 9/11 and into the poisonous politics of the Iraq War. They rode the downward spiral of economic recession with fewer resources, and now see a kind of naked hostility at nearly every level of public exchange. “A brutish and short” America is the only one they have ever known and their anxiety in the face of it is palpable.

My kids’ life prospects are already poor. Their genes may already be altered forever by stress. I wonder: are they merely at the extreme end of vulnerability in America, or are they also canaries in an increasingly toxic coalmine, telegraphing to us with their bodies that we should also be afraid.

+ + +

It was great to hear from several of you after recent posts about defending your reputation “as a good person” when it’s challenged. Thanks, as always, for reaching out and letting me know what you think.

It was great to hear from several of you after recent posts about defending your reputation “as a good person” when it’s challenged. Thanks, as always, for reaching out and letting me know what you think.

This post was adapted from my October 7, 2018 newsletter.