When we set out to make a difference with our work, we usually are. It empowers us by doing it and empowers others who are trying to change the same things. It’s the belief in possibility that makes a new year, well…doable.

I came upon a guy last week who begins his day reading these phrases:

This is the beginning of a new day. You have been given this day to use as you will.

“What you do today is important because you are exchanging a day of your life for it.

“When tomorrow comes, this day will be gone forever. In its place is something you have left behind…let it be something good.

However “make the most of it” that sounds, it’s about whether we dare to face forward and declare ourselves because none of us has an unlimited number of days ahead of us when we can.

Historian David McCullough has written a dozen or so highly acclaimed biographies about Americans like Teddy Roosevelt, the Wright Brothers and John Adams. (You may also know him as the sonorous voice behind some of Ken Burn’s public television documentaries.) When he was interviewed about Truman, McCullough discussed this same quandary: whether to bother standing up for what’s important when it’s so easy to give up before you’ve even started.

The interviewer began by noting that “your writing makes readers feel like they are there,” and McCullough replying that his writing this way is deliberate.

What I’m trying to do is show readers—especially young readers—that things didn’t have to turn out as well as they did. I want them to know that life felt every bit as uncertain to people back then as it does to us today.

There were these moments when they had to be thinking, there is no way we can get this bridge built, or get this canal dug. But things worked out—because individuals behaved in certain ways, with integrity and resilience. They figured out how to work with other people, and they tried to do the right thing.

And my hope is that these stories will inspire some readers to behave the same way in the face of the uncertainty in their lives.

I found the immediacy and uncertainty before what happens next to be most compelling in McCullough’s 1776. But for tiny acts of imagination and courage all coming together 250 years ago, America would never have happened. And I can be a part of the same miracle today—if I choose to.

In a strange twist of fate several years later, McCullough found himself talking with his new internist about the Truman interview, about how today is no different than it was in the past, and the amazing things we might accomplish by acting despite today’s uncertainties.

I try to make that point in every interview. It’s really the main reason I do the work I do.

McCullough’s rationale for his lifetime of work is sharing this knowledge. Everyone who went on to accomplish something important could just as easily have sat it out, yielding to fear or inertia It’s not just a perspective for the young but for those at every stage of life who have a limited time ahead to leave behind something that they can be proud of. And finally, It’s not only advice for opinion writers or biographers, but for everyone who employs their skills on the gamble that they just might achieve a good result.

Writing this morning, it is easy to see 2019 as a gathering mess. No wonder people are looking for “unicorns” like Beto O’Rourke “to save the coming day for us” so we don’t have to get down into the trenches and do the hard work ourselves. But why not be a part of it, putting the faith in our own judgments instead of in a savior’s, particularly when so much that’s good has already been achieved in our lifetimes?

I can’t be reminded enough about the positive side of the ledger that’s laid out in Steven Pinker’s books like Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018) (according to the data: life, health, prosperity, safety, knowledge, and happiness are all on the rise, and not just in the West, but worldwide), which builds on his earlier The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011) (that we’re living today in the most peaceful era in history). Like David McCullough, the perspective of time helps me to overcome my excuses and failures of nerve.

In the last couple of days, there was also Greg Ip’s helpful column looking both back at the past year and forward into the new one in the Wall Street Journal. Ip called it “The World is Getting Quietly, Relentlessly Better,” and he begins it with a promise:

If you spent 2018 mainlining misery about global warming, inequality, toxic politics or other anxieties, I’m here to break your addiction with some good news: The world got better last year, and it is going to get even better this year.

But what I liked the most about the column was his conclusion after reviewing the data about rising incomes and global progress.

Perhaps it…feels irresponsible to celebrate the many ways the world is quietly getting better because it distracts from the fight against things that are loudly getting worse: polarized and authoritarian politics, deadly opioids, nuclear proliferation, and most of all, a warming climate—a consequence of all those new middle-class entrants burning fossil fuels.

Yet obsessing over [these remaining] perils is how we’ll likely solve them.

Ip is saying that with focus and forward momentum—we can do this, and I happen to believe he’s right. We still have the hard work of planting the seeds that are there, but the ground is also in better shape than our sky-is-falling fears like to admit.

I wrote several posts last year about the threat of technology that arrives and is widely embraced before its downsides are known or anyone has had a chance to put reasonable safeguards in place. Social networks and smart phones today, with drone deliveries and autonomous vehicles soon to follow. The ethicist in me kept asking: “Just because we can do it doesn’t necessarily mean that we should, at least before we understand more of the implications than we do now.” So last year felt like frantically catching up with the aggregators who are selling our personal data and the too-big-for-our-own-good companies that no one worried about soon enough. Much of the time, it felt like not having enough fingers for the holes in the dike.

But still I railed against the privacy profiteers like Facebook and Google (for the sake of our ability to make decisions without manipulation) and monopolists like Amazon (because the free flow of goods and labor really is important). And all the while, others with similar sensibilities were jumping into these trenches too, with no certainty that anything would come of it. Well, this past week saw several news stories about progress that is being made where I doubted it ever would.

A story on January 11 announced that AT&T, Verizon and T-Mobile would no longer be sharing their users’ location data with those who are selling it to trackers because of privacy concerns that had been raised. Yesterday, Sprint followed up with the same decision. It was a victory (for now) over some of the tech giants with a brand new cohort of privacy advocates behind it.

Last Friday, there was a news report that customers, investors and employees are challenging Amazon’s facial recognition software because of similar privacy concerns. A group of nuns who are also investors have submitted a resolution for a vote at Amazon’s annual shareholders meeting. The company has refused thus far to halt the sales of personal data generated by its software, but it has been forced into a dialogue it would never have had without widespread pushback.

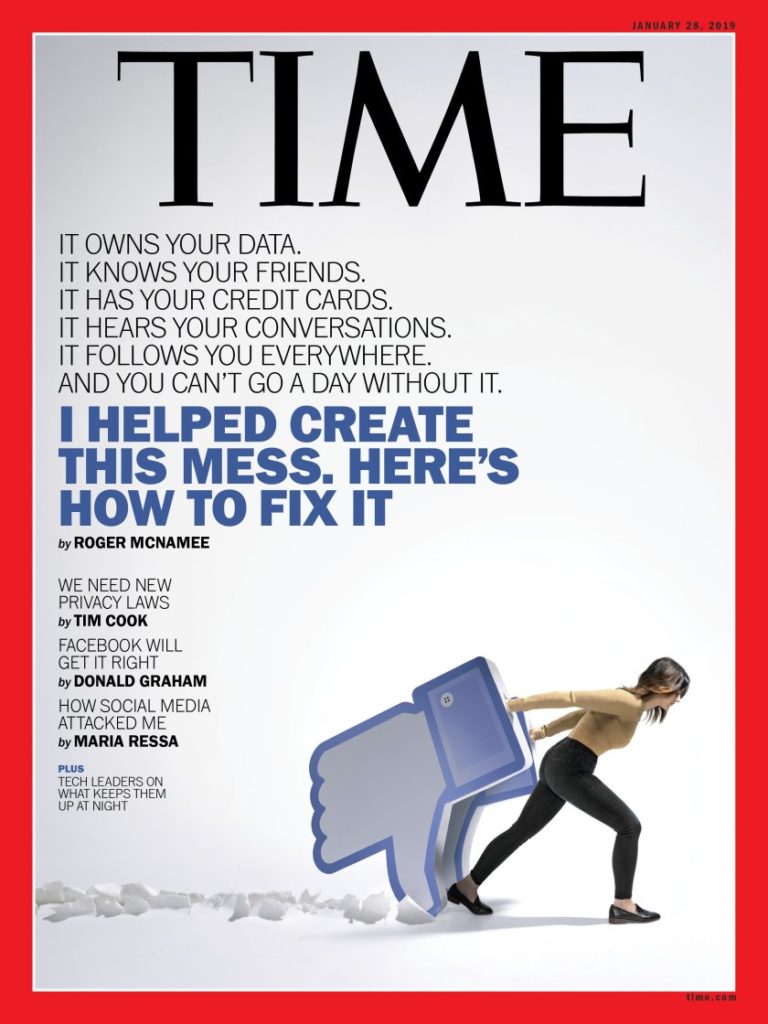

My favorite marker from last week also speaks to the critical mass of individual voices that have been building, one by one, against Facebook even when the odds against them seemed most daunting. Roger McNamee, an early investor in the company, was one of them. Despite becoming rich, having a personal relationship with Mark Zuckerberg, sitting on Facebook’s board for a time, and being a prominent member of the insider’s club in Silicon Valley, McNamee was one of the first to challenge Facebook’s excesses that nobody could ignore. It took his early critical statements along with the past 9 months of populist backlash to culminate in Time’s cover story this week—a testament to how voices both big and small can coalesce into a wave.

I want to mention something else too. I’m hardly a frontline tech commentator, but Roger McNamee signaled me through Twitter yesterday after I profiled his essay in Time. I’m not telling you this because it’s cool that he did but because taking a stand in your work, however you can, often puts you in the company of those you can be proud to be associated with. The experience of this kind of solidarity also helps me to forsake the safety of my fence and dive into the fray even when I’m reluctant to do so in the work that stares back at me every day.

It’s not just pushing the same rock up the hill, only to have it roll back down to its same old place. There is progress when I look for it, and I’m almost never alone.

There’s a wooden arch at our backyard entrance. It’s heavy with wisteria branches that are hung (as if for the holidays) with seedpods.

A few years ago, when Brendan Ryan’s painting crew was here gentrifying the place, I was outside, by this archway, talking to one of his painters when a prior generation of seedpods started popping like firecrackers, propelling their seeds loudly and with amazing velocity in all directions. It happened in March, with some change in temperature or water pressure that neither of us could feel triggering the explosion. We laughed when we realized what was happening, and eventually fell into quiet to absorb the miracle of it.

The wisteria was thrusting itself into the future.

Of course, we need more than nature’s rhythms to motivate us to get up and keep doing good work for another day or year. Plants also don’t make excuses, or have the luxury of feeling hopeless when their time has come.

But there are markers that bolster optimism when I bother to look, that help me to believe that I’m neither Sisyphus nor going it alone. Perspective. A record of progress. Occasions of solidarity. It’s about winning the game in my head so I have another day’s worth of fortitude to win it outside.

This post was adapted from my January 20, 2019 newsletter.

Leave a Reply