It’s been a busy week for me, and not in a good way.

It was probably RSV that took down the first three days of it in a torrent of congestion and runny nose, until I felt my old self begin to return on Thursday, only to discover while heading out for necessities, that the rapid thaw had burst two pipes in our carriage house (which holds both car and office) so I ended up spending all of my relief mopping, moving, drying and hoping that my plumber would come to the rescue.

By Friday I was tired, back to recovering and not yet relieved again, but Andrew the unflappable pipe fixer had come and gone and it now appears that I’ll finally be getting rid of the old computer equipment that’s been gathering out there because I never got around to removing “the sensitive bits” before it’s composting until now.

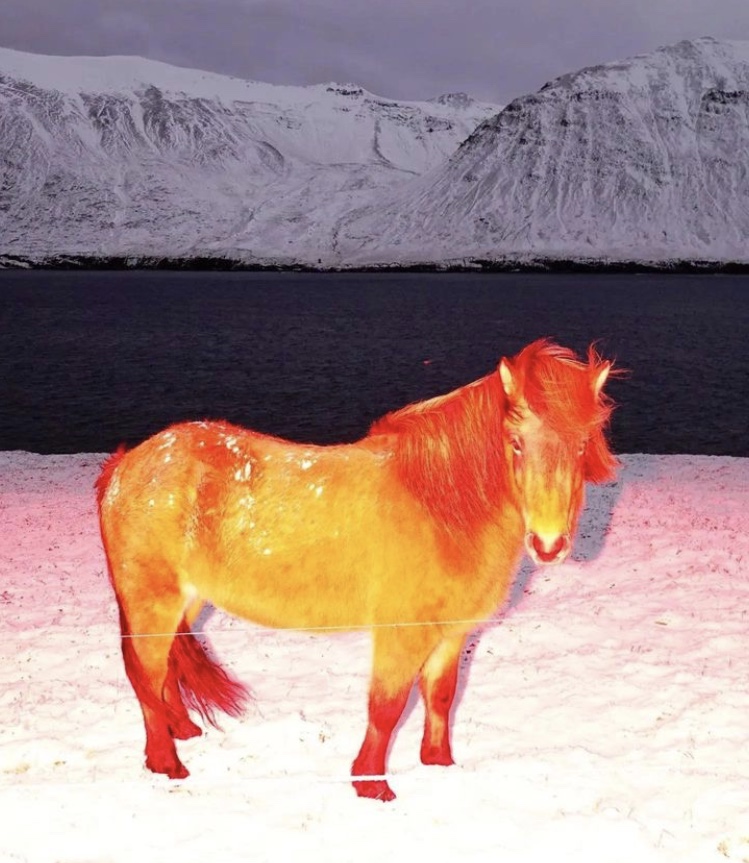

If all of this has to happen, it might as well be in this dangling participle of a week, lodged between a culmination of sorts (on Christmas) and a new beginning (today, on New Years). While I was casting about for a headline image this morning, it seemed to me that the one above is either about capturing the last or the first light, and therefore, just that kind of inbetweeness. (Photographer Sasha Elage gets my thanks for it.)

In a similar vein, this is also a time of year for looking back on some of its high points and maybe anticipating some new ones. I covered some of the songs that held my ear in 2022 last week, and today it’s a short dash through things I’ve read that have left their mark on me this year and might do the same for you.

However, before turning to my short list of books, essays and stories, a observation about the current state of our literacy (more generally) from, of all people, Henry Kissinger. Nixon’s Secretary of State is 100 years old now and looking a bit like Stephen Hawking while he retreats into his business suit at gatherings, but God-Bless-Him the man is still raising concerns and speaking out about them given his undiminished sense of public duty. It’s remarkable, but also invaluable—especially because so few of our “public figures” work up the gumption to do so today.

Henry Kissinger as the Ghost of Christmas Past, Present and Future.

Above everything, Kissinger is concerned that our culture is losing the academic-and-life-long commitments to “deep literacy” that its road warriors seemed to have earlier in his career. That is: To know what our greatest minds are thinking about, to be able to talk about those things too, and most importantly, to discern the most telling insights in this cultural conversation and apply them to how we live and work, govern ourselves and interact with strangers. He believes that there used to be more public-spirited individuals with a deep understanding of history, world affairs and human interaction (from literature, among other sources) who were prepared to lead their communities or countries.

Kissinger fears we are losing the farm teams and even the starting benches of leadership that our civilization once depended on because the men and women who are drawn to public service no longer bring “the deep literacy” that our colleges and universities once fostered. There are lots of reasons for this of course, including an emphasis on “vocational” education (or only-study-now-what-you-can-get-paid-to-do-later) and on the STEM disciplines (given remarkable advances in science and technology and the high-paying jobs that accompany them).

But Kissinger cites two other culprits, both related to the growing dominance of electronic communication today. Increasingly, “we gain what we know” from pictures or tweets instead of from reading about something (anythng) in any greater depth. A constant barrage of brief impressions has caused us to have shorter attention spans and made us less likely to take any kind of dive (let alone a deep one) into complicated subject matter. Kissinger fears that our leaders and “the educated strata” in our societies that once produced their brain trusts are becoming increasingly “less literate,” with consequences that we can unfortunately see all around us.

It’s a point that social psychologist Jonathan Haidt also made this year in an Atlantic article called “Why the Past Ten Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.” Anticipating Kissinger’s alarm, this article was already “one of the year’s best reads” and the subject of my Divided We Fall post six months ago. Haidt argues that social media, and its appeal to emotion instead of reason, has increased our civic illiteracy, making it harder to safeguard the institutions and commitments we profess to hold in common. While, like many of you, I was briefly heartened by the U.S. mid-term elections in November, the coming year is likely to remind those of us in the US (with our new Congress) and elsewhere (given widening conflicts and fresh horrors) just how fleeting that “good news” really was.

Today’s undermining of literacy is not somebody else’s problem. I know only too well how much “easier” it is for me to scroll through photo or video-sharing sites or watch “what Netflix recommends for me next” than to commit to a lengthy essay or a new book. So I sense the cognitive degrading in and around me too, a lassitude that the pandemic and other travails has only amplified, and I actively try to vote against it—although not as much as I’d like.

So with that somewhat sobering preface, allow me to share my other favorite “reads” of the year and hopefully an occasion or two for you to cast your own votes for “deeper literacy” over easier diversions.

(photo by Leo Berne)

2 MORE ESSAYS AND ONE STORY

– Eula Biss, “The Theft of the Commons,” in The New Yorker, June 8, 2022. I have one of you to thank for this one (“Happy New Year, Tedd!”) This essay is about private property versus the land as well as the other privileges and freedoms that we still hold “in common.” It turns on the author’s visit to the farming community of Lawton in rural England where the common resources that everyone depends on have somehow resisted the private interests that keep wanting to gobble them up.

Laxton has a tight center where the farmers all live within walking distance of the pub. This makes it distinct from all the rural places I have known. Standing at the center of the village, I had the feeling that I was standing inside an idea, an idea about how to live in relationships of necessity with other people. I felt at home in the idea, and I puzzled over this for a moment, feeling held close by the tight center of a village where I had never been, wondering if I was making myself at home in my own imagination.

It’s imagination that we need now in places like the unclaimed oceans and polar regions, the Amazon and Congo River basins, the rainforests and coral reefs, and where the water flows down the Colorado and towards an American desert that tries to sustain more people than it ever expected.

– Lucas Mann, “An Essay About Watching Brad Pitt Eat That is Really About My Own Shit,” at Hobartpulp.com, August 16, 2022. From its title, you might be wondering what this could possibly have to do with “making the world a better place” at the humanities end of the pool. Well I wouldn’t have found out either if I hadn’t already been thinking about Brad Pitt’s screen persona and the impact that seeing somebody like him over and over might have on an even mildly susceptible person.

Pitt has never chosen to not be Brad Pitt in the image on-screen. Even as he’s taken strange, anti-careerist roles, earned that character-actor-trapped-in-a-leading-man cliché, each performance comes attached to the promise of Brad Pitt’s body. He may have done a wacky Irish Traveler accent in Snatch, but he was still a boxer, and there was a slow-motion break in the movie’s frantic comedy to watch him pull off his shirt. It’s almost as if he’s set himself a lifelong artistic challenge — I can believably be anybody, even when I look like this. Or there’s that lingering, glorious possibility that he hasn’t considered his body enough to wonder whether it’s a gift or a hindrance. Or maybe it’s a moral decision, honoring what has always been the money-maker, refusing to take on that greatest and easiest bit of artifice, the physical kind, even in a profession all about playing pretend.

By getting an imprint like this into the right author’s head, great literature (and this comes close) can change the way that you see the world. Mann confronts the shame of his personal cravings around food, his tendency to be overweight, and his desire that his new daughter be free of these burdens in the shadow of Pitt’s treating food like another accessory to his preternatural good looks. Above even Mann’s powers of observation and serious writing chops, this autobiographical tour-de-force is about how “what we see” might never stop affecting “who we are” once “it gets under our skin.”

“Watching Brad Pitt Eat” is another cautionary note in an era that’s full to the gills with damaging, media-driven impressions, and not just the ones that are made on vulnerable, 13-year-old girls (although in my post next week, called Watching in 2022, one of my favorites was a advertisement for Dove soap that showed “the nearly parental effect” that Instagram or TikTok can have when it’s urging these same 13-year olds to strive for greater beauty.)

– Alyssa Harad, “To Live in the Ending,” in Kenyon Review, July-August, 2022.

When you live in a time that can feel almost apocalyptic you deeply appreciate new ways to frame “the imminent threats” you’re constantly facing. In gorgeous “braids” of storytelling, Harad manages to do just this by weaving several endings in her own life with the “end times” stories that echo around her in order to make more manageable sense out of the harrowing times in which we live. For example, the voice of an environmentalist that she’s followed:

offers a way to think about the end of the world not as a singular explosive event—something true only from the long view of geological time—but as a Chinese box or a matryoshka doll. In a time of climate emergency we live in a series of nested crises. When we emerge from one, the larger one is always there waiting for us. And inside the big troubles—the global rise of fascism, a kleptocratic presidency, white supremacist police violence, concentration camps on our southern border, a pandemic—the smaller crises of ordinary human life continue—a broken heart, a sick child, the rent falling due—all of it framed, structured, intensified, and continually interrupted by the ongoing alarm of the climate crisis.

So how does nesting these crises cushion their blows? Because doing so allows us to acknowledge the occasional victories that occur within them and, when that happens, to feel their respites (if only briefly).

The rolling flow of Harad’s narrative allows us to experience what she means by this: the epiphany of blue flowers in a dying lakebed or of the heroism of a public defender who works “within but against a violent system, quietly, in an obscurity that makes the work possible, trading purity for efficacy, jimmying open the places where the edges don’t quite come together, to make room for a few more people to breathe.”

Shadow & light packets.

BOOKS

– I have piles of unread books, but not a finished one that’s worth sharing since I extolled the virtues of a slim volume about effective writing and a short memoir by “one of our great innovators in modern autobiographical writing” over the summer. In a post called The Relaxing Curiosity That Is Also August, I have more to say about Verlyn Klinkenborg’s “Several Short Sentences About Writing” and Margot Jefferson’s “Constructing a Nervous System: a Memoir.” (Both of them are still sending me reminders.) You’ll find quotes, links to reviews and other impressions that I had about them in that post.

– I follow the second half of the year-in-books quite closely, in particular the National Book Award finalists and longlist for American writers, the same winnowing down for the Booker Prize given to a book that’s written in English this year, and the “notable” and “best” books according to book editors at the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and other literary arbiters. I do it because I want to know what I should be reading next.

One compilation of note came via a daily post from the publishing industry—a kind of compilation of compilations for the year’s fiction and non-fiction books and “the 10 Very Best Books for 2022 Overall” when the categories are combined. This is how Publisher’s Lunch (yes, it conveniently drops at lunchtime everyday) describes the operation of this remarkable annual service:

Below as usual are our top 10s for the year — based on 61 ‘votes’ from a variety of highly selective lists from critics and reviewers, award nominees, bookseller and librarian picks, book club selections and more.

(“And more!”) You see, they’re aiming to measure quality here, not the quantity of books sold. So in the coming year, if you’re looking for a book to read that comes highly recommended by (apparently) all the right people, their “10 Very Best Books for 2022 Overall” are as follows:

1. Trust, Hernan Diaz

2. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, Gabrielle Zevin

3. Our Missing Hearts, Celeste Ng

4. If I Survive You, Jonathan Escoffery

An Immense World, Ed Yong

6. The Rabbit Hutch, Tess Gunty

I’m Glad My Mom Died, Jennette McCurdy

8. Babel, R.F. Kuang

Constructing a Nervous System, Margo Jefferson

Demon Copperhead, Barbara Kingsolver

All This Could Be Different, Sarah Thankam Mathews.

(I am at a loss as to why there are 11 books on their top 10 list. It must be the “ties” at #8 that are responsible.)

– And last but hardly least, here are the 3 books that I’m currently standing-in-line to take out of my local library. One I was after long before I saw the list above (Ed Yong’s “Immense World” about the infinite varieties of living experience that are flourishing around us but that we know so little about).

A second is also on the list, but I only got interested in it after the buzz from delighted readers I trust gradually became so deafening that I felt like I’d be missing out otherwise (Gabrielle Zevin’s “Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow” about the origin story of video games and how friendships can sometimes be “as complicated, perplexing and rewarding as a great love story.”)

Finally, a book that came to my attention outside of any list (Claire Keegan’s “Foster,” set in rural Ireland and full of the rich details of daily life, but composed with an artfulness that promises to linger and gnaw. What I know of the plot—about a temporarily-loved girl—has shown me more than enough about why this just might be true.)

If these three live up to their evangelists, I may be writing to you about them here in coming months too.

In the meantime, to you and your loved ones, I wish you all the best in the coming year. Keep in touch and may the wind be at our backs in the months ahead.

This post was adapted from my January 1, 2023 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes I post the content from one of them here. You can subscribe (and not miss any of them) by leaving your email address in the column to the right.

Leave a Reply