What the Chinese are thinking about us is no laughing matter if we’re listening to experts talk about how they are holding America’s mortgage with one hand and stealing our most valuable secrets with the other. But our worries could become more realistic if we also considered just how much the Chinese admire us and the way of life they think we have going on here.

There is always something valuable to be learned when others are both coveting and admiring what you have. As La Rochefoucand famously said: “Sometimes we think we dislike flattery, but it is only the way it is done that we dislike.” Thinking about what we like and don’t like about how many of the Chinese people view America today has some interesting things to teach us about ourselves.

I had the chance to visit China a couple of years back.

I’m glad I went when I did and probably wouldn’t recognize much of the place today. It was a few months before the Beijing Olympics, and the country was moving so fast you could almost feel the wind. But what I remember most was how excited regular folks—particularly young people—were that we had come all that way to see them.

They tried out their English on us and surrounded us for pictures. We were their chance to sample America, in the same way that they were already sampling KFC and Polo Ralph Lauren. At the time, analogizing their admiration to eating or wearing did not seem entirely misplaced.

This inkling got some support when I came upon a piece about “architectural mimicry” in China. While the copycat buildings that are springing up there aren’t always American buildings, easily the most duplicated structure in China today is the White House.

The building serves as the model for everything from seafood restaurants to single-family homes to government offices in Guangzhou, Wuxi, Shanghai, Wenling and Nanjing.

There are duplicate Chrysler Buildings and other Manhattan skyscrapers too.

That “imitation is the sincerest form of flattery” is certainly part of it. But it’s more than this, and has many antecedents in this ancient civilization. Emperors regularly built parks with an Epcot Center of facsimile structures from remote lands. Both then & now, it is a pretty straightforward effort to enhance their legitimacy by demonstrating China’s de facto appropriation of the known universe.

Today, the Chinese are trying to swallow other aspects of the American way of life as well.

Much of the dynamism you can feel in China today results from a billion people embracing capitalism all at once. It was a forest of timeless bamboo scaffolding clinging to a mountain range of 21st century construction projects that really brought this home to me when I walked around Beijing. Since almost everybody in China wants to become the next Bill Gates or Warren Buffett, it is hardly surprising that the American rags to riches fantasy has also been made available for mass consumption.

It’s been turned into the equivalent of a fortune cookie.

The Chinese love short motivational phrases even more than Americans do, if that’s possible. They have been a vehicle for transmitting community values from Confucius to Mao, and they are still in active use today. Only now it’s so-called American values that are being conveyed, and what’s being shared has a lot more to do with individual fortune than collective harmony.

Evidence of this comes from the apparently spontaneous rise of 20 or so “allocutions” or commandments that many people in China today believe are written on the walls of Harvard’s library. These commandments speak to the commitment, diligence and self-denial that are supposedly bolstering their counterparts’ remarkable performance here in the States.

One says, “Happiness will not be ranked, but success will—at the top,” while another envisions a slightly different, though related reward, “If you study one more hour, you will have a better husband.” Struggling through exhaustion to get where you’re going is key in this messaging: “Nodding at the moment, you will dream. While studying at the moment you will come true,” and similarly, “Most great achievements happen while others are dozing.” Perhaps most succinct of all is this commandment: “Please enjoy the unavoidable suffering.”

Wherever it comes from, this distilled wisdom about American motivation clearly haunts the Chinese imagination. In an article about the phenomenon by Robert Darnton, Harvard’s university librarian, we learn that:

the allocutions took root in China’s educational system and were widely used in primary schools, in English courses, on exams, and even in interviews for admission to Beijing University. They have appeared on bulletin boards, in newspapers, on telecasts, on a website of China’s Ministry of Commerce and on Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter. Above all, they have reached millions through the Internet, thanks to endless transmission by blogs, including one that registered 67 million hits.

As a result, it should come as no surprise that the most numerous queries on Harvard’s “Ask the Librarian” web page are about these allocutions, with many of the questions originating in China. When informed that no such commandments appear on the walls in any of Harvard’s 73 libraries, Mr. Darnton records the following responses: “Well my teacher has been using this fooling me,” and “Are you kidding? We grown up with these mottos.” Or even more interesting: “Thank you for liberating us” and “When I know the truth I can’t stop crying.”

Of course, there are both comforting and disquieting things about tokens of flattery like this, as well as the fact that Chinese people will probably be eating fried chicken in a mock-up of the White House later today.

For example, we may like it that the Chinese think we’re this successful, but disquieted by their distortion of us into sleep-deprived automatons. It’s like Eleanor Roosevelt’s ambivalence about one of her tributes: “I once had a rose named after me and I was very flattered. But I was not pleased to read the description in the catalogue: no good in a bed, but fine up against a wall.”

The good news about admiration is the often accurate perception that there is something about us worth admiring.

Even when it is somewhat alarmingly expressed, flattery indicates that somebody out there still thinks you’re ahead in the big game.

But there can be another message too.

Whenever there’s a gapping hole between what’s being hungered for and what is actually true, it may be time to torque up that big game of yours before it’s too late.

(On this last day of the Chinese New Year, great prosperity to all!)

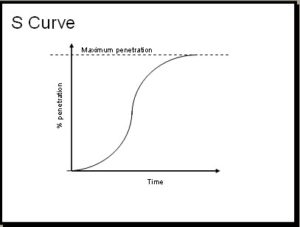

The authors use a familiar graph that illustrates how innovative products rapidly penetrate markets to show us how bringing new knowledge or innovation into our jobs can change our individual work experiences just as dramatically. The graph they re-purpose to make their argument is called the S-curve.

The authors use a familiar graph that illustrates how innovative products rapidly penetrate markets to show us how bringing new knowledge or innovation into our jobs can change our individual work experiences just as dramatically. The graph they re-purpose to make their argument is called the S-curve.