I want to share with you a short, jarring essay I read in the New York Times this week, but first a little background.

For some time now, I’ve been worrying about how tech companies (and the technologies they employ) harm us when they exploit the very qualities that make us human, like our curiosity and pleasure-seeking. Of course, one of the outrages here is that companies like Google and Facebook are also monetizing our data while they’re addicting us to their platforms. But it’s the addiction-end of this unfortunate deal (and not the property we’re giving away) that bothers me most, because it cuts so close to the bone. When they exploit us, these companies are reducing our autonomy–or the freedom to act that each of us embodies.

Today, it’s advertising dollars from our clicking on their ads, but tomorrow, it’s mind-control or distraction addiction: the alternate (and equally terrible) futures that George Orwell and Aldous Huxley were worried about 80 years ago in the cartoon essay I shared with you a couple of weeks ago.

In “These Tech Platforms Threaten Our Freedom,” a post from exactly a year ago, I tried to argue that the price for exchanging our personal data for “free” search engines, social networks and home deliveries is giving up more and more control over our thoughts and willpower. Instead of responding “mindlessly” to tech company come-ons, we could pause, close our eyes, and re-think our knee-jerk reactions before clicking, scrolling, buying and losing track of what we should really want.

But is this mind-check even close to enough?

After considering the addictive properties of on-line games (particularly for adolescent boys) in a post last March, the reply was a pretty emphatic “No!” Games like Fortnite are using the behavioral information they syphon from young players to reduce their ability to exit the game and start eating, sleeping, doing homework, going outside or interacting (live and in person) with friends and family.

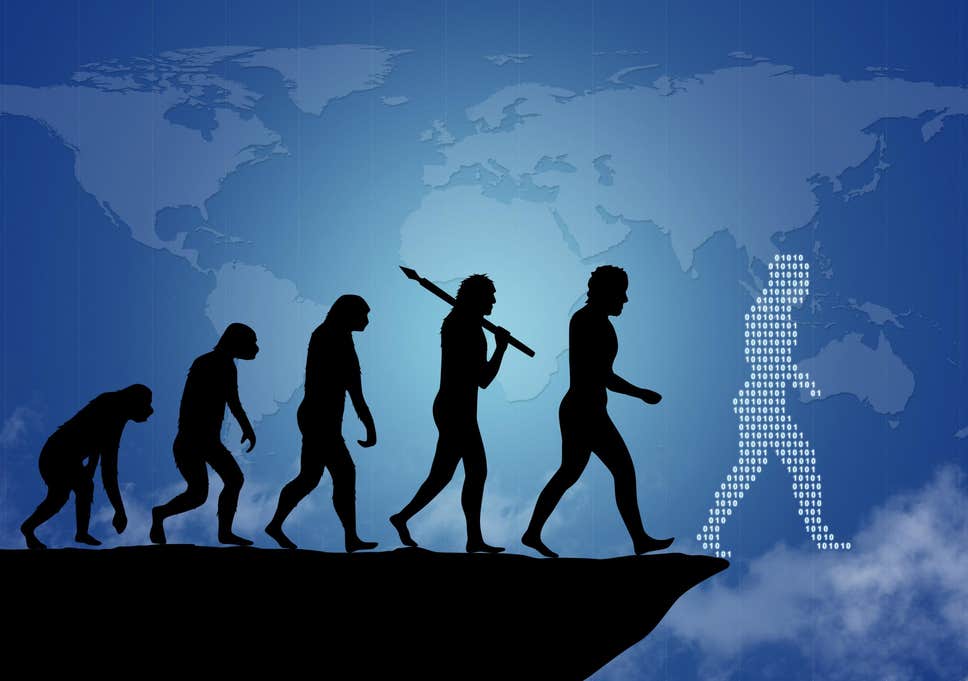

But until this week, I never thought that maybe our human brains aren’t wired to resist the distracting, addicting and autonomy-sapping power of these technologies.

Maybe we’re at the tipping point where our “fight or flight” instincts are finally over-matched.

Maybe we are already inhabiting Orwell’s and Huxley’s science fiction.

(Like with global warming, I guess I still believed that there was time for us to avoid technology’s harshest consequences.)

When I read Tristan Harris’s essay “Our Brains Are No Match for Our Technology” this week, I wanted to know the science, instead of the science fiction, behind its title. But Harris begins with more of a conclusion than a proof, quoting one of the late 20th Century’s most creative minds, Edward O. Wilson. When asked a decade ago whether the human race would be able to overcome the crises that will confront us over the next hundred years, Wilson said:

Yes, if we are honest and smart. [But] the real problem of humanity is [that] we have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology.

Somehow, we have to find a way to reduce this three-part dissonance, Harris argues. But in the meantime, we need to acknowledge that “the natural capacities of our brains are being overwhelmed” by technologies like smartphones and social networks.

Even if we could solve the data privacy problem, humanity will still be reduced to distraction by encouraging our self-centered pleasures and stoking our fears. Echoing Huxley in Brave New World, Harris argues that “[o]ur addiction to social validation and bursts of ‘likes’ would continue to destroy our attention spans.” Echoing Orwell in Animal Farm, Harris is equally convinced that “[c]ontent algorithms would continue to drive us down rabbit holes toward extremism and conspiracy theories.”

While technology’s distractions reduce our ability to act as autonomous beings, its impact on our primitive brains also “compromises our ability to take collective action” with others.

[O]ur Paleolithic brains aren’t build for omniscient awareness of the world’s suffering. Our online news feeds aggregate all the world’s pain and cruelty, dragging our brains into a kind of learned helplessness. Technology that provides us with near complete knowledge without a commensurate level of agency isn’t humane….Simply put, technology has outmatched our brains, diminishing our capacity to address the world’s most pressing challenges….The attention [or distraction] economy has turned us into a civilization maladapted for its own survival.

Harris argues that we’re overwhelmed by 24/7 genocide, oppression, environmental catastrophe and political chaos; we feel “helpless” in the face of the over-load; and our technology leaves us high-and-dry instead of providing us with the means (or the “agency”) to feel that we could ever make a difference.

Harris’s essay describes technology’s assault on our autonomy—on our free will to act—but he never describes or provides scientific support for why our brain wiring is unable to resist that assault in the first place. It left me wondering: are all humans susceptible to distraction and manipulation from online technologies or just some of us, to some extent, some of the time?

Harris heads an organization called the Center for Humane Tech, but its website (“Our mission is to reverse human downgrading by realigning technology with our humanity”) only scratches the surface of that question.

For example, it links to a University of Chicago study involving the distraction that’s caused by smartphones we carry with us, even when they’re turned off. These particular researchers theorized that having these devices nearby “can reduce cognitive capacity by taxing the attentional resources that reside at the core of both working memory and fluid intelligence.” In other words, we’re so preoccupied when our smartphones are around that our brain’s ability to process information is reduced.

I couldn’t find additional research on the site, but I’m certain there was a broad body of knowledge fueling Edward O. Wilson’s concern, ten years ago, about the misalignment of our emotions, institutions and technology. It’s the state of today’s knowledge that could justify Harris’s alarm about what is happening when “our Paleolithic brains” confront “our godlike technologies,” and I’m sure he’s familiar with these findings. But that research needs to be mustered and conclusions drawn from it so we can understand, as an impacted community, the risks that “our brains” actually face, and then determine together how to protect ourselves from it.

To enable us to reach this capable place, science needs to rally (as it did in an open letter about artificial intelligence and has been doing on a daily basis to confront global warming) and make its best case about technology’s assault on human autonomy.

If our civilization is truly “maladapted to its own survival,” we need to find our “agency” now before any more of it is lost. But we can only move beyond resignation when our sense of urgency arises from a well-understood (and much chewed-upon) base of knowledge.

This post was adapted from my December 15, 2019 newsletter. When you subscribe, a new newsletter/post will be delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning.

A place for “inner cultivation” stands apart from the rushes of stimuli that are so easy to get lost in every day. It’s a space for wondering whether there are deeper satisfactions than the ones that you have now. It’s a time to explore whether you have the desire for anything more.

A place for “inner cultivation” stands apart from the rushes of stimuli that are so easy to get lost in every day. It’s a space for wondering whether there are deeper satisfactions than the ones that you have now. It’s a time to explore whether you have the desire for anything more.