I’m reminded that we know very little about the land we live and work on.

Too often, we have no “sense of place” beyond our familiarity with the surface improvements that make our houses or workplaces more comfortable and attractive, efficient and accessible.

We rarely know—or try to discover—stories about “our” land’s prior visitors, inhabitants and laborers, or how it looks different today than it did before our childhoods or the settlers came or the glaciers rolled over it.

It’s not our fault if it’s never really occurred to us.

But I was reminded this week that I feel more grounded or connected when it does occur to me.

Among other things, little knowledge or even curiosity about the land we live and work on may explain some of the indifference we feel (and that I sometimes feel) towards climate change and global warming. How abstract it is and why we don’t relate to it more.

Because our plots of land are relative strangers to us, we don’t embrace them with the same protective bonds that draw us, to say, a child under threat. Instead, they are sometimes little more than addresses, places to arrive at or depart from but not necessarily learn more about even while we’re spending most of our time there.

There are other explanations for this disconnection, of course. Most of us no longer work our land for sustenance and fewer of us even “keep it up,” leaving that job to yard crews or a neighborhood kid with a lawnmower. As a result, we know less and maybe care less about where our land has been and might be headed, what it needs (beyond lawn food and holiday lights) and what secrets it might hold.

I started learning about where I live today by working the grounds after moving in. I’d come to love “groundwork” because I’d done so much of it “around the house” as a kid. We had a 3/4 acre size yard where I grew up, and by around 8 or 9 my job became taking care of the grass, the snow and leaf removal, and the landscaping, such as it was. I was always digging around, moving something from here to there, making the place look like someone cared about it. I learned about this place, my home, by getting my hands into it and sometimes around it on a regular basis.

My childhood yard had a big slice of the meadow that Meadow Circle Road in Branford was named after. That was one thing it had been before my father built a house on it, with help from lanky old Mr. Bartholomew who still lived in a far greater house a stone’s throw away. There’d been Native Americans there too, leaving pathways through the trees that we still walked on, along with the occasional arrowhead. I must have brought this kind of place-memory and curiosity about its long cast of characters to the new plot of land we found ourselves on after coming to Philadelphia.

It barely had a yard when we moved in and layer on layer to dig through before finding any more of one. There were rows of boxwood that had spilled outward into every space we had out back that hadn’t already been colonized by similarly neglected grapevines. There were tufts of saplings on the side that no one had plucked out after their seeds had fallen from the yard’s tulip, chestnut, ginko, cherry and copper beech trees.

I started appreciating my new yard’s back-story (as opposed to the sweaty hours it kept demanding) when I learned from its last owner how the house gardener used to live in the enclosed porch. As if for the first time, I saw how human and natural forces had conspired to create the complexity of overgrowth that confronted me every time I stepped outside.

Breaking the ground to remove or plant something provided deeper information. For example, near the rambling magnolia that was lost to a winter storm a couple of years ago, I found some pottery shards that looked Colonial-era, at least to me. A historical marker a few streets away might have explained them when it noted: “this was the site of the British encampment before the Battle of Germantown in the late summer and early fall of 1777.” Or maybe I’d just found some broken crockery in a farmhouse dump from when my yard had extended beyond some previous dwelling into fields of wheat or root vegetables long before regular trash days had ever been imagined. This week I remembered that I should still be wondering as well as poking around for more clues.

Is there more from that dump or encampment out there? Since none of us are here for very long, what will I leave behind for the next caretaker? What should I want him or her to find?

Every piece of land doesn’t hold surprises like these pottery shards of course, but as Robert MacFarlane recently observed while discussing his new book (called Ghostways), “There are rarely innocent landscapes,” by which he meant, I think, ones untrammeled by complicated pasts that await our discovery. He reminded me of old life-lines like these fragments of pottery, about the likelihood of additional ones that extend through the ground and towards the surface, and how place memories such as these might provide a deeper kind of education (and maybe a more necessary one) than I can find anywhere else.

+ + +

Thinking about the land I’m on like this brought me back to those final scenes in the movie Avatar, where James Cameron conjured (in sight and song) swaying braids of native people under a sacred tree whose roots gave them life and returned them to earth when it was time.

Until the middle of last year, Avatar held the record as the highest grossing movie ever, but it was likely more successful at entertaining us than at suggesting a richer way of seeing how humans are bound up with the land.

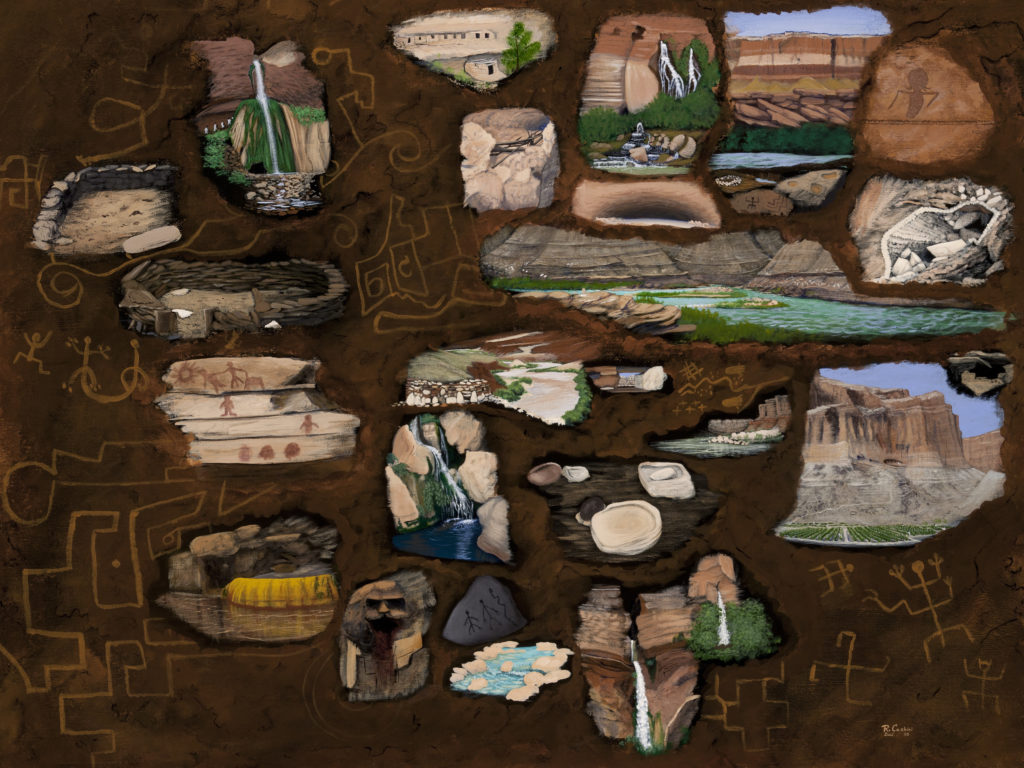

This week, a similarly appealing but out-of- the-mainstream way of solidifying this relationship was captured in a short video posted on Aeon.com. It’s about how the native Zuni people of New Mexico have recently been involved in “a counter-mapping project” with the aim of capturing their experience of the land in ways that two-dimensional American maps (with North on the top, South on the bottom and a mileage calculator in the corner) or Google Map’s aerial views never do.

The Zuni mapping project illustrates the difference between knowing where something is and understanding what it means to be there.

A Zuni map like this one tries to record a people’s visual “knowledge of place.” It doesn’t “eclipse” native language and ways of seeing but tries to capture “vignettes of experience” viewers will recognize, not only in the rivers, gorges, plains and rocks that they see around them but also in what they’ve been singing and telling stories about since they were children.

Maps like these are one more way to teach new generations and remind older ones about their roots and dreams, where they’ve been and hope to return, what is significant to them and what is not. Above all, they are a way of navigating through life and work, with the land and their connections to it as perhaps their most important points of reference.

If you’re interested in more information about the Zuni mapping project and in watching a slide-show that includes several more maps by native artists, here’s a link that will take you to it. And because the Zuni are not unique among native peoples, you can also read and download a discussion here about maps and map-making by Australia’s aboriginal people.

They too were reminding me that this is as good a time as any to understand where you are, dig into what it means to be there, and deepen your sense of place.

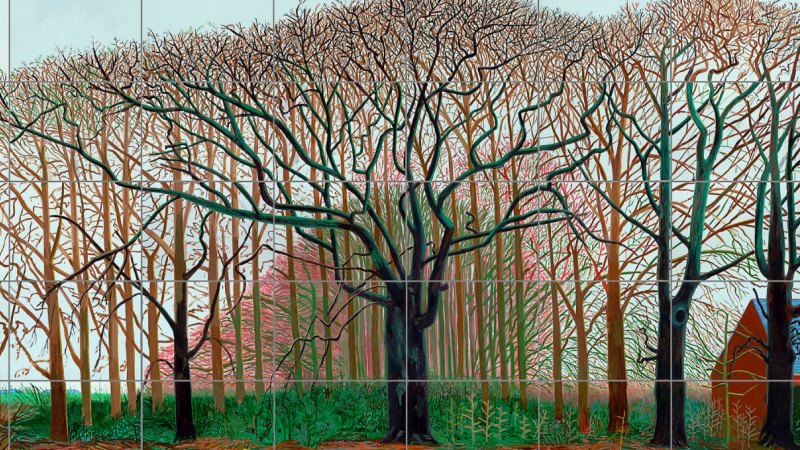

The image up top is of several panels from David Hockney’s 2007 painting “The Bigger Trees Near Warter.”

This post was adapted from my November 29, 2020 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning. You can subscribe by leaving your email address in the column to the right.