There are three extraordinary aspects to the storytelling in Marshall, a new movie appearing in theaters this week.

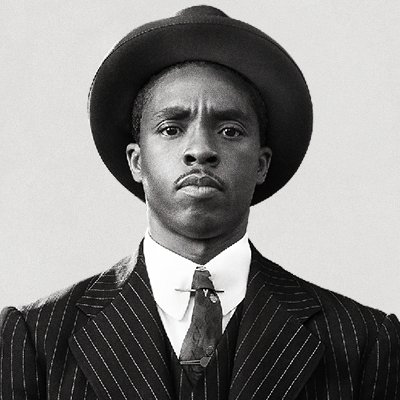

Its protagonist, Thurgood Marshall, was the first African American to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court. Several years before he took the bench, Marshall argued Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, a high court case that found state laws establishing separate schools for black and white children to be unconstitutional. But long before his career peak or landmark victory, Marshall was a young NAACP lawyer struggling to represent a black defendant who was charged with raping a white woman.

That courtroom is where most of this movie takes place, and it’s the first story element that struck me. Marshall was virtually unknown back then. He seems to think he’s “all that,” but unlike the swaggering hotshot that we’re meeting for the first time, we know something that he doesn’t, namely, all that he’ll go on to accomplish. This absence of knowledge means that it could be anybody’s bright future that glitters in his eyes.

The second arresting feature is Marshall’s complicated, flawed personality.

We meet a whip-smart prankster who can be charming but also full of guile. In action, his bravado makes him the life of the party one minute and an arrogant jerk the next.

Before the Connecticut case, we see Marshall enjoying the high life of jazz era Harlem. But he also decides to leave his beautiful wife and celebrity friends behind to fight for civil rights in some of the most hostile corners of America. To leave these comforts for a life of combativeness and fear is either the definition of foolhardy or tremendously courageous.

It is the ambivalence of these details that enable us to share in his story. Brazen but also exposed, this Marshall is never too good to be true. It may have been the bright future in this man’s eyes and his relatable personality that caused Chicago’s Chance the Rapper to buy out two theater seatings of the movie—his announcement appears below—so that kids from his old neighborhood could encounter a role model who feels like the real thing.

What really got my attention though was the third turn that the story takes.

As the trial unfolds, Marshall confronts the fact that he is an out-of-state lawyer who cannot speak for himself or his client in this courtroom. Because he was not admitted to practice in Connecticut, Marshall literally has to “speak through his local counsel,” a young insurance attorney unversed in either criminal law or racial animosity. In other words, without his rhetorical skills and righteous passion, what everyone knows is Marshall’s best hand has been tied behind his back and that he has to learn to fight without it.

Chadwick Boseman, the actor who plays Marshall, described this element of the story in an interview when the movie was released:

Jeffrey Brown: You wanted to make your big courtroom speech?

Chadwick Boseman: Had to, you know. But the more I read it, I realized that this was the exact obstacle that would make the movie interesting. The truth of the matter is, when you’re acting [in the courtroom scenes] you’re silent. Your non-verbals are dialogue, subtext. And that’s actually just as hard, if not harder, than having the huge speech at the end….

Of course it is. A lot harder.

The young Thurgood Marshall was a black lawyer in a hostile community that had already made up its mind about the guilt of his client. The future of the NAACP, particularly financial support for the organization, depended on his success in cases like this one. As if these pressures weren’t enough, Marshall had to improvise his client’s defense with an untested accomplice at his side. He didn’t know where his attitude and talents would take him, but they would have to be enough. And all the while, he carried his own baggage.

During the same interview Reginald Hudlin, the film’s director, emphasized that the Marshall he wanted to portray was not an angel but a saint. He explained the difference this way:

Well an angel kind of implies perfection. A saint means, you know, you push through your humanity. You do something greater than.

That’s what Chance the Rapper wanted those young audiences in Chicago to see. A flawed individual, not unlike them, pushing through his circumstances and his humanity.

There is some real hope in that.