We hear a lot about the dangers and “hallucinations” of AI as we test-drive our large language models. At the same time, we probably hear too little about how AI is helping us to advance our body of knowledge by processing huge volumes of data in previously unimagined ways. The benefits don’t always outweigh the risks, but sometimes they do—and in an unprecedented fashion.

I’m thinking today about how AI-driven assessments are starting to tell us whether social policy “fixes” that we implement today are actually achieving their intended results instead of speculating about their possible “pay offs” 10 or 20 years later. These new assessments can help us to determine “the returns on our investments” when we attempt to improve our society by (say) providing paternity leave for fathers, multiplying our social connections, or enhancing the stock of affordable housing in vibrant communities.

Artificial intelligence is already enabling us to identify and refine the variables for public policy success beforehand and to keep track of the resulting benefits in something that approaches real time.

I’ve written here several times about how too many of us are failing to achieve the American Dream. Straightforwardly, that’s whether our economy is affording our nation’s children the opportunity to do better economically than their parents over succeeding generations. For Nobel Laureate Edmund Phelps, attaining that American Dream provides a “flourishing” that brings both us and our children psychic benefits (like pride and enhanced self-esteem) as well as greater prosperity and foreward momentum. We calculate the likelihood of its returns in measures of opportunity—from having many opportunites to improve ourselves to having almost none available at all.

Over the past 90 years, for millions in the U.S. (or nearly everyone whose family is not in the top 20 percent income-wise) the quest to attain the American Dream has been disappointing at best, soul-crushing at worst. Our inablity to reliably improve either our fortunes or those of the generations that succeed us unleashes a cascade of unfortunate consequences, such as widespread pessimism about the future, cynicism about our politics, an ever-widening gulf between economic “winners” and “losers,” a rise in “deaths of despair,” and a willingness to gamble on a leader who promises “a new golden age” but never reveals how anyone “who hasn’t gotten there already” will be able to reach it.

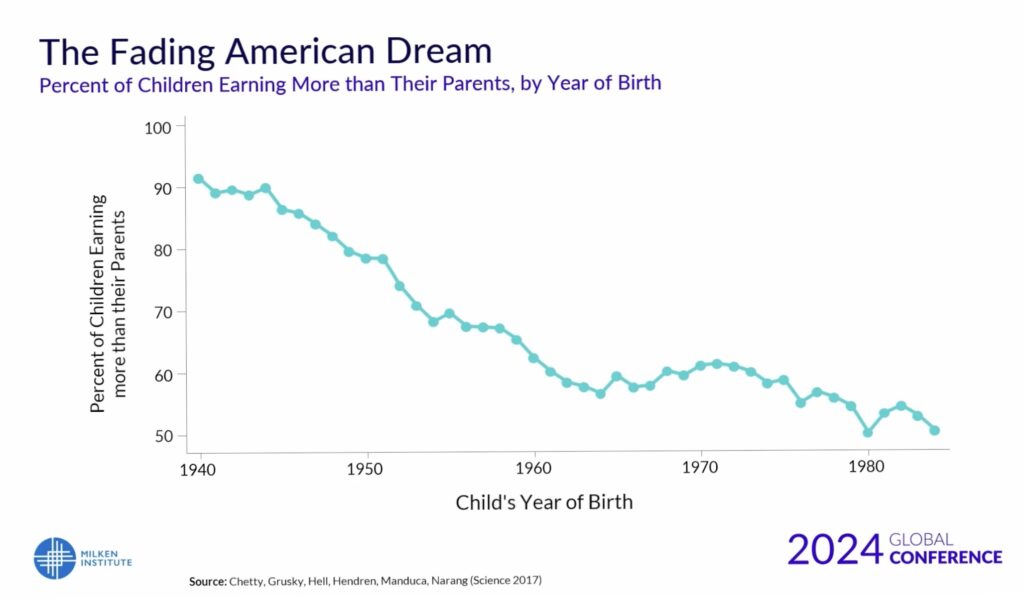

This is a chart, from a presentation at the Milken Institute by economist and Harvard professor Raj Chetty, includes income measures from tax returns for both parents and their children (both at age 30). Using AI tools, it tracks “the percent of children earning more than their parents” through the mid-1980’s. (The overall percentage has not improved between then and now.) Today, like in 1985, it is “essentially a 50/50 coin flip as to whether you are going to achieve the American Dream.” (A link that will enable a closer view of this chart, along with others included here, is provided below.)

During the New Deal of the 1930s and Great Society of the 1960s, a raft of social programs was launched to give Americans “who worked hard and were willing to sacrifice for the sake of better tomorrows” greater opportunities to improve their circumstances and live to enjoy “the even greater success” of their children. Unfortunately, our prior attempts to engineer the “economic playing field” so that it delivers the American Dream more reliably have often been little better than “shots in the dark.”

For instance, many New Deal initiatives didn’t succeed until the economic engines of the Second World War kicked in. The “anti-poverty” programs of the Great Society bore fruit in some areas (such as voters’ rights) while causing unexpected consequences in others, like the weakening of low-income families when welfare checks effectively “replaced” fathers’ traditional roles as breadwinners. In those days, policymakers meant well but lacked the assessment tools to know whether their fixes were working until 10 or 20 years out, when they’d sometimes discover that the original problem persisted, or the collateral damage from the policy itself became evident.

Today, new policy-making tools are eliminating much of this guess-work. AI-driven data gathering, experimentation within different communities, and almost “real-time” assessments of progress have begun to transform the ways that new economic policies are developed and implemented. Raj Chetty, the teacher and economist pictured here, is at the forefront of this sea change.

I’m profiling his work today because of the results he, his team and his fellow-travelers in this big-data-driven space are beginning to achieve. But this work also injects a note of optimism into an increasingly pessimistic time. Policy delivery like Chetty’s points towards a future with greater economic promise than the majority of us can see today–when inflation persists, tariffs threaten even higher prices, and government safety nets are dismantled without apparent gains in efficiency. What Chetty calls his “Recipes for Social Mobility” (including his starting point for the chart (above) provide a methodical, evidence-based way to craft, implement and assess the durability of economic policies that could help to deliver the American Dream to millions of anxious families today.

In recent months, Chetty has been doing a kind of “road show” that profiles the early progress of his AI-driven approach. I heard a lecture of his on-line from New Haven three weeks ago, which led me to another talk that he gave during a 2024 conference held at the Milken Center for [yes] Advancing the American Dream in California. The slides and quotations today are from Chetty’s Milken Center presentation and can be given either a listen or a closer look via this link to it on YouTube.

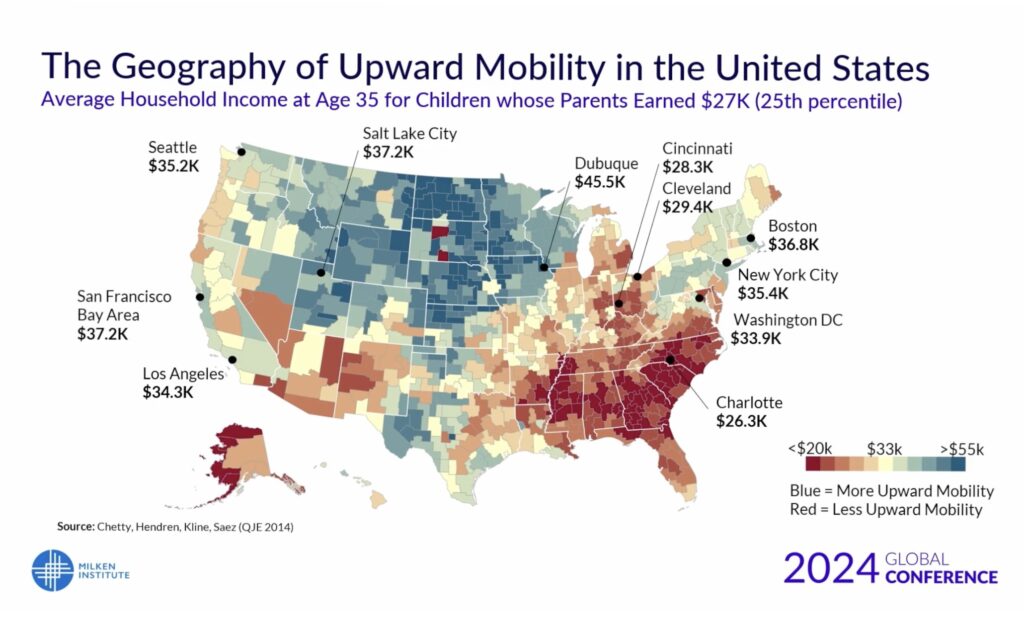

After his first chart about “the fading American Dream,” Chetty presented an interactive U.S. map built upon meticulously assembled data that shows areas in the country where the children of low income parents have “greater” or “lesser” chances at upward social and economic mobility. Essentially, his team gathered income data on 20 million children born in the 1980’s to households earning $27k per year in order to determine how many of those children went on to earn more than their parents—adjusted for inflation—at age 35, localized to the parts of the country where they were living at the time.

Chetty’s Geography of Social Mobility chart.

You’ll notice—somewhat surprisingly—that in this snapshot, kids of low-income parents enjoyed the greatest upward mobility in Dubuque, Iowa while actually losing the most ground compared with their parents in Charlotte, North Carolina over this time frame.

I had some additional reactions (beyond my amazement at the richness of the data painted here). For one thing, if I were on Chetty’s team, I would use colors other than “red” and “blue” to illustrate differences in upward mobility across the U.S. Using this color palette falls too easily (and unnecessarily) into our current Red and Blue state narratives, or exactly the kinds of prejudices that tying communities to actual data are trying to dispel.

While I watched Chetty talk about this slide, I also noticed you can scan a bar code that allows you to examine places that you might be curious about in closer detail (such as where you live) by putting in your zip code when prompted. When I did so, I already suspected that a child’s shot at upward mobility would be relatively low in my Philadelphia neighborhood, but was surprised to learn that it is far higher in many of the central Pennsylvania counties that have long been characterized as “a gun-loving, God-fearing slice of Alabama” between here and Pittsburgh.

While he spoke, Chetty highlighted “the microscopic views and comparisons” that a mapping tool like this allows, particularly when it confounds expectations. He describes, for example, how appalled Charlotte’s civic leaders were when learning about their “worst place finish” in this assessment and how it catalyzed new, similarly data-driven efforts to improve the prospects for that City’s children.

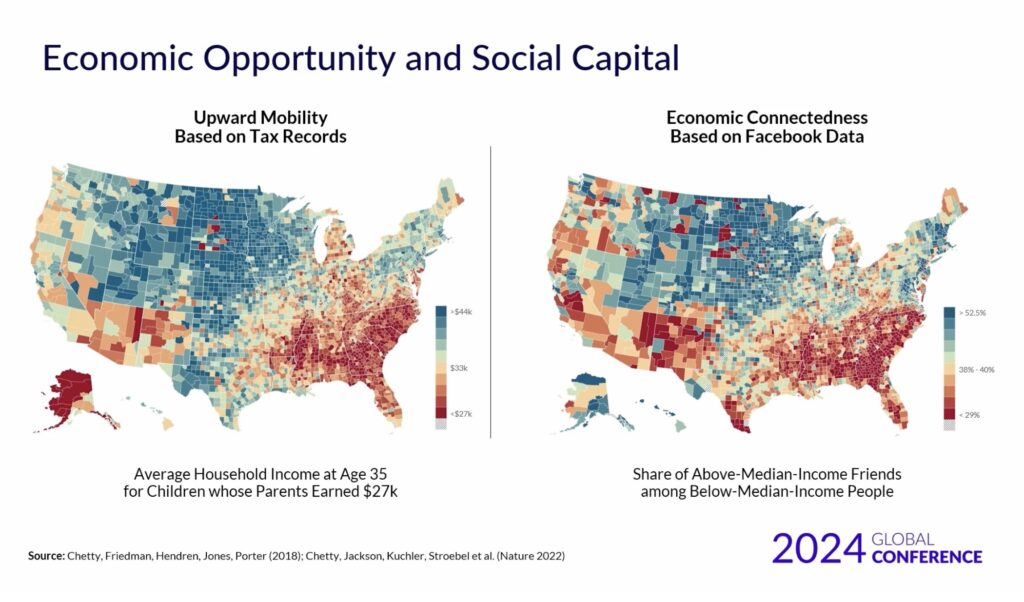

Chetty goes on to juxtapose this chart with an even more interesting one. At first glance one sees its similarities, but its differences are far more intriguing.

Contrasting places in the U.S. where there is Economic Opportunity (or Upward Mobility) with places where there are greater or lesser amounts of Economic Connectedness and the kind of Social Capital that it produces.

The social capital that Chetty illustrates here is the same “commodity” that Bowling Alone’s Bob Putnam has been trying to build throughout his career, as described in my post a couple of weeks ago, “History Suggests that Better Days Could be Coming”. Putnam’s thesis goes like this: if you want to improve your community, state or nation, that drive begins by strengthening your in-person social connections, thereby increasing “the social capital” that’s available for spending when connected individuals wish to solve a problem or better their community’s circumstances.

At it’s simplest, Chetty’s comparison chart shows those places in America where people from different socio-economic backgrounds are more connected to one another, less connected and where there are greater or lesser accumulations of social capital as a result.

Chetty once again reminds us that localizing massive data sets in this manner allows those using these tools to dive even deeper into neighborhood, or even into street-by-street variations in both upward mobility and social capital.

In his “economic connectedness” map, social capital acrues from the amount of “cross-class interaction” that occurs between high and low income people in each county, town and neighborhood in the U.S. This relationship is key because Chetty’s team had already established that “the single strongest predictor of your chances of rising up is how connected you [or those most in need of “upward mobility”] are to higher income folks,” as opposed to living in a place where nearly everyone is on the same rung of the economic ladder.

To compile this chart, Chetty collaborated with Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook’s “core data science team” to access the voluminous data the social network has gathered on the 72 million Americans who use the platform. He wanted to identify low-income users and determine how many “above median income friends” each one of them has, before breaking that aggregate snapshot down with his powerful mapping tool.

Connections across income classes produce opportunities “like getting a job referral, or an internship.” But Chetty also identified an “aspirational” component when members of different economic classes interact with one another on a regualr basis.

If you’ve never met somebody who went to college, you don’t think about that as a possibility for you. If you’re in a community where you’ve seen more people succeed in certain career pathways, that can change kid’s lives…

Once again, a few of my reactions to the comparisons these big-data snapshots invite.

A detailed view of the mid-Atlantic in general, and Philadelphia in particular, on Chetty’s mapping of Economic Connectedness.

Despite Philadelphia’s “relatively weak” score on upward mobility, I was also not surprised that my part of the state ranks as “relatively strong” (or a medium shade of blue) when it comes to the social capital that’s produced by our economic connectedness. Among many other things, that means those of us in Southeastern Pennsylvania already have a relatively-strong foundation for driving greater upward mobility, along with more helpful data about our localized advantages and challenges as we dig deeper into our particular blocks on this map.

On the other hand, I found the social policy solution that Chetty profiled in his talk somewhat disappointing, although it seemed to me that the experimental template that gave rise to it would be a serviceable-enough incubator for additional policies going forward.

He describes at length a test study his team initiated in Seattle involving low income households with subsidized (formerly Title 8) housing vouchers. Their first discovery was that most voucher holders try to use them in their own communities, with little or no gain in economic connectedness. They then realized that while “real-estate brokers” are commonly used for finding places to live in higher income communities, their eqivalent is non-existent for those who want to get “the most bang for the buck” out of the $2500 credit in one of these housing vouchers.

Chetty’s team concluded that if a sponsor (e.g. a local government, for-profit or non-profit) wanted to build social capital for low-income households, it could spend what amounted to 2% of the value of each voucher to hire “brokers” to help low-income residents find housing in communities with greater economic connectedness than the uniformly impoverished neighborhoods where most of them lived.

This solution was affordable and it quickly built social capital for low income individuals, but even under the best of circumstances it is unlikely to impact enough households because of the limited amounts of affordable housing in most higher income communities, a fact that Chetty readily admits:

I don’t want to give the impression that I think the desegregation approach, moving people to different areas, is the only thing we should do. Obviously, that’s not going to be a scalable approach in and of itself.

But this demonstration of how to engineer a social policy illustrates the potential for modeling and testing reforms that can attract “smarter, evidence-driven investments” as mapping tools like these are refined and used by more policy makers.

Chetty’s Seattle experiment also puts a spotlight on social programs that increase economic connectedness. While the parents who were able to move from low income communities to mixed income neighborhoods surely had an opportunity to realize gains in social capital, it’s their children who stood to benefit the most from more diverse schools, better playgrounds and exposure to career options they might never have considered before.

What motivates Chetty, his team and his hosts at the Milken Institute the most are the opportunities that these AI-driven, data-rich tools will be presenting in the very near future to the millions who are pursuing the American Dream but failing to achieve it.

Twenty years ago, a civil rights organization that sought to open pathways towards college and upward mobility had, as its memorable motto: “A mind is a terrible thing to waste.”

With a conclusion as obvious as that in mind, I’ll give Raj Chetty’s final presentation slide some of the last words here about assets that we’ve been wasting for far too long.

The box reads: “If women, minorities, and children from low income families invent at the same rate as high-income white men, the innovation rate in America wouild quadruple.“

I guess I would prefer to make this slide more powerful still.

It’s true that we’re wasting many of our most valuable people-assets in the US. today, but “delivering the American Dream more reliably” is not the legacy of “high-income white men.” First off, many of our most successful innovators today aren’t “white” but are people of color, immigrants and their descendants (like Chetty himself). Moreover, this is an 80%-of-America size problem (or everyone who’s NOT in the top 20% income-wise) not a burden that’s only carried by previously marginalized communities. I believe that Chetty’s ground-breaking work will attract the base of support that it deserves if slides like this are imodified to reflect the true magnitude of our Lost Einsteins. So I don’t know how Chetty’s team quantified the “lost opportunities” highlighted here “as quadruple” the number of our current innovators, but I’d wager that’s an undercount.

+ + +

For those who are interested, I’ve written about our frustrated pursuit of the American Dream several times before. These posts include:

- “The Great Resignation is an Exercise in Frustration and Futility” (citing data that government management of the economy has caused our middle and lower classes to realize essentially the same income due to government transfer payments, arguing that perverse incentives such as “these redistributions of wealth also stifle upward mobility”);

- “Let’s Revitalize the American Dream” (citing a 2015 study that found the U.S. ranks “among the lowest of all developed countries in terms of the potential for upward mobility despite clinging to the mythology of Horatio Alger”); and

- “America Needs a Rebranding Campaign” (If “equality of opportunity” is really our touchstone as a nation, then it “needs to infuse every brand touchpoint” of ours, including our “packaging, public relations, advertising, services, partnerships, social responsibility, HR & recruitment, loyalty programs, events & activations, user experience, sourcing & standards, and product portfolio.” In other words, America needs “to start walking the equality-of-opportunity walk,” instead of just talking about it.)

This post was adapted from my March 9, 2025 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes I post the content from one of them here in lightly edited form. You can subscribe by leaving your email address in the column to the right.