I’ve been finding lately that the biggest obstacle to feeling the common beat is other people.

It’s just easier to imagine sharing the rhythm and release—that universal correspondence environmentalists always wax-on about—when it’s all of the other living things and people aren’t involved. Just the animals that hop, the birds that soar, the fish that ride the waves and the trees that are always reaching towards the sun: you wouldn’t call any of them mean, selfish or lost in their petty concerns. They all know (all the time) that they need “the rest of their world” to live and thrive, as I was reminded in a brilliant episode of Nature this week called “Soul of the Ocean.” But we’ll get to that….

I was in John’s yoga class this week and finding it even more of a blessing than usual after way too much work (“Thanks, man!”). He began, as he always does, with a reading to pull us from the preoccupied places we’d brought with us to where he always hopes to take us. This is some of the bridge that he thought might help us out last Thursday, from The Book of Awakening:

If you place two living heart cells from different people in a Petrie dish, they will in time find and maintain a third and common beat. (Molly Vass) This biological fact holds the secret of all relationship. It is cellular proof that beneath any resistance we might pose and beyond all our attempts that fall short, there is in the very nature of life itself some essential joining force. This inborn ability to find and enliven a common beat is the miracle of love. This force is what makes compassion possible, even probable. For if two cells can find the common pulse beneath everything, how much more can full hearts feel when all excuses fall away?

This drive toward a common beat is the force beneath curiosity and passion. It is what makes strangers talk to strangers, despite the discomfort. It is how we risk new knowledge. For being still enough, long enough, next to anything living, we find a way to sing the one voiceless song. Yet we often tire ourselves by fighting how our hearts want to join, seldom realizing that both strength and peace come from our hearts beating in unison with all that is alive.

I know, I know. This sort of thing is for the chanting voices, murmuring drums and free-floating love in a yoga room, not for life on Philadelphia’s “Blade Runner”streets, where we’re hitting and running and shooting the life out of our neighbors except, of course, when the Eagles are on TV. (It’s worth noting here that “in an earlier life,” John had been a police officer.)

Because this post is about the kind of heart that yearns to beat with all the others that are alive, and further, because Valentine’s Day will be giving us its own version of that before too many more days, I thought of another attempt to capture the common beat in this City.

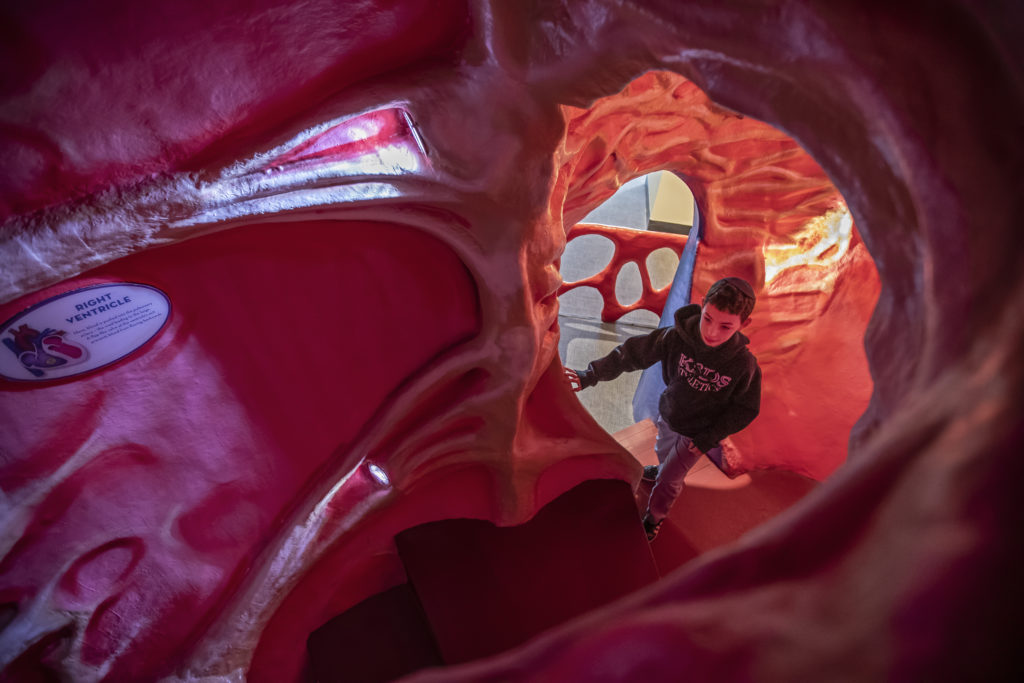

At the Franklin Institute, which is our science museum, there’s been (since the year after I was born) a Giant Heart that (at 28-feet wide and 18 feet high) is said to be big enough to fit into a 220-foot tall person. For several of the decades that followed, it was a rubbery cavern where streams of school children would relieve themselves until its smell became so intolerable that “a deep cleaning” was performed and a new advertising campaign was launched—as you can see at the top of this page.

Pictures of that Giant Heart itself follow as we explore (first) how living things have often evolved into finding the common beat in nature and (last) how supposedly lower forms of life can coral supposedly higher forms of life into doing their bidding because both have come to embrace that we’re all “in this” together and might as well help one another out when called upon to do so.

There are a million examples in nature that show us how we can flourish by sharing instead of destroying the world around us. But we’ll have to broaden the limited reading of human advancement that we’ve enshrined in our ideologies and other excuses to truly see them.

In an interview in the Times this week, author (Braiding Sweet Grass) and scientist Robin Wall Kemmerer chastened capitalists generally, and (I think) American capitalists in particular, when she said:

Unquestionably the contemporary economic systems have brought great benefit in terms of human longevity, health care, education and the liberation to chart one’s own path as a sovereign being. But what are the costs that we pay for that? ….We have to think about more than our own species, that these liberatory benefits have come at the price of extinction of other species and extinctions of entire landscapes and biomes, and that’s a tragedy.

Can we derive other ways of being that allow our species to flourish and our more-than-human relatives to flourish as well? I think we can. It’s a false dichotomy to say we could have human well-being or ecological flourishing. There are too many examples worldwide where we have both, and that narrative of one or the other is deeply destructive and cuts us off from imagining a different future for ourselves.

Another concept besides “freedom” that includes our aspirations as well as punishments is “survival of the fittest.” While the concept has unquestionable evolutionary benefits, ever since “forward thinkers” dragged it under the canopy of Social Darwinism it has also produced tragedies, including thinking that our dominance, subjugation and pillage are the necessary (collateral) damages for our social advancement. But in addition to motivating centuries of conquest, colonialism, and “milking of the Earth,” the continuous need to demonstrate that “we’re the fittest” has also given us the distorted picture that we’re only operating in the ways that Mother Nature does.

The problem is: the natural world doesn’t operate in this one-sided way and never has, however much we want to anthropomorphize its internal dynamics to feel greater comfort about our own means and ends.

In a recent book called Sweet in Tooth and Claw: Stories of Generosity and Cooperation in the Natural World, science writer Kristin Ohlson takes our mistaken alignment with this social theory on directly:

Even many scientists don’t grasp how pervasive cooperative interactions are in nature. Consequently, we seem to have developed a zero-sum view of nature, suggesting that whatever we take . . . comes at the expense of other living things and the overall shared environment.

To challenge this self-serving view, Ohlson cites the remarkable “give-and-take” that happens throughout nature, including in the soil that’s as close as our back or front yards. Microbes, fungi, wild flowers, scrubs and trees not only share nutrients and dispose of waste, they also message one another via neural-like networks that actually “challenge what we mean by cognition.” Reading this I was reminded of the new “Avatar” movie and (like in the original) its subsurface webs of mutual aid, support and resilience that the colonists missed until they “crossed-over” into the natural world. While Darwin himself hardly needed reminding, Ohlson introduces the rest of us to one of his contemporaries, Russian scientist Peter Kropotkin, who wrote the following at the same time that Social Darwinism was on the rise:

Who are the fittest: those who are continually at war with each other, or those who support one another? We at once see that those animals which acquire habits of mutual aid are undoubtedly the fittest.

Fittness, then, is more complicated than simply surviving or coming out on top. It also includes a great deal of cooperation.

If you still have any doubt, I recommend the visual and (sometimes) spoken-word feast of Nature’s “Soul of the Ocean” episode this week. (Here’s a link to watch this “never-before-seen look at how life underwater co-exists” on whatever viewing device you happen to be using.)

This nature documentary invites us “to dive into a better world.” It’s a place where “everywhere you look, fish aren’t eating one another but cleaning each other.” There seems to be “an older alchemy” where all of the inhabitants are playing in a vast game with rules that hold the entire playing field in a delicate balance. Some of it is “surely the ancient biochemistry of cooperation.”

My favorite examples included the colorful goby fish who maintains a permanent relationship with a tiny shrimp “that does its housecleaning” during their lifetimes together. (Off the coast of the Philippines where they live, it’s said that one has never been seen without the other.) In other examples, each clown fish has “its own” stinging anemone for protection, and species of fan coral have their own identically-colored species of seahorses. A carrier crab gives a poisonous urchin a ride, perhaps for additional protection, while in a gorgeous sequence on traveling jellyfish streaming long tentacles behind them we get a glimpse of “a delicate medusa fish” hitching a ride “in a fragile mobile home”—or maybe something else is going on, since we can never stop understanding nature through our excessively human ways of looking at things.

Nor do all examples of mutuality in nature seem fair, or fully balanced. Just because cooperation is needed to maintain the overall harmony, one party in a shared arrangement may have the far easier job—and it’s often not the one you’d expect who ends up “running things.”

“Make sure you all visit the bathroom before going inside.”

It’s easier for us to imagine that when one party in nature seems to come out on top while the other seems to be working “much, much harder,” the over-worker must be staying in the relationship out of “love,” or at least some “alchemy” or “biochemistry” that we still can’t totally fathom. Such is the case with a parasitic plant that gets a rare island rabbit to continuously do its evolutionary bidding, a startling new story that’s still revealing its secrets somewhere on the Amami Islands off the coast of Japan.

The plant is balanophora yuwanensis (no friendly name has yet been given, so just “BY” for now). It’s a bundle of “strange, red globes” that (straight out of “Avatar”) look like “strawberries crossed with red cap mushrooms.” Instead of producing the energy that it needs from photosynthesis, BY leaches its sustenance from the roots of other plants, making it parasitic by nature. The developing mystery involves how BY—with bad tasting seeds and no wind to carry them about—has managed to propagate itself throughout these remote Islands.

Enter the only dark-furred rabbit in the world (called, somewhat unimaginatively, the Amami rabbit.) This past week, two Japanese scientists documented “an evolutionary bargain” in which the root-sucking BY gives food in exchange for this rabbit’s seed dispersal services, an arrangement “that [apparently] has never been documented between a mammal and a parasitic plant” before.

Nocturnal filming allowed the scientists to capture Amami rabbits regularly chowing down on BY’s less-than-appetizing “strawberries” and “red caps.” Meanwhile, a follow-up investigation revealed that considerably more viable seeds were able to pass through these rabbits’ digestive systems than those of other seed-consuming rabbits. As if that weren’t enough, the Amami species conveniently likes to burrow (and release the BY’s seeds) at the base of large trees and close to a new host plant’s roots (or exactly the food source that baby BYs will need access to).

“In other words,” according to these scientists, “the rabbits’ dropping patterns are less random [and infinitely more desirable] in the evolutionary eyes of the parasites.” Unfortunately for us, while revealing this extraordinary example of inter-reliance between species, the research has yet to explain why Amami rabbits are attracted to these unappealing seeds in the first place, or agreed to do almost all of the work in this admittedly unusual relationship.

Now imagine (if you can) a similar example of cross-species reliance where the supposedly less sophisticated species somehow convinces the more sophisticated one to do its bidding. In this scenario, Wally the resident terrier, who’s playing the role of the dominating plant, somehow convinces the author to play the gullible, hard-working rabbit in yet another “evolutionary bargain.”

As I’ve eluded to in recent posts, Wally has been suffering from a serious digestive aliment and it’s been requiring higher amounts of medication (including steroids) to kick the nasties out of his system. The meds also make him thirsty and drink far more water than usual. Well this past week began a life-on-steroids regime that involves my taking him outside to pee every few hours (whether I’m asleep or not) if I wish to avoid accidents in the bed (his preferred place for sleeping, of course) or elsewhere. How did my little guy negotiate this evolutionary advantage I wonder as I stagger down the stairs every night at 12, 3 and 6 am, put on my parka and brave the sub-freezing temperatures in order to “accommodate the two of us”?

In other words, how did another “plant” convince his “rabbit” to do this?

I guess it brings me back to John, The Book of Awakening, the Franklin Institute’s “love our heart” promotion, all the LOVE that’s wafting around this “brotherly love” kind of city, as well as the “older alchemy” and “ancient biochemistry” of cooperation that exists among species in nature. When two hearts beat side by side, at some point they become “a common beat” that makes cooperation, compassion and (yes) even Love possible.

Through all of his life Wally has done everything that his pure little heart can do for me so, of course, I’ll endeavor to do the same for him. While I’ve not always been happy to be “the rabbit to his plant” this week, I also can’t imagine acting in any other way.

This post was adapted from my February 5, 2023 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes I post the content from one of them here. You can subscribe (and not miss any) by leaving your email address in the column to the right.