Some of us believe that entrepreneurs can lead us to a better future through their drive and innovation. Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and, at least until recently, Elon Musk fill these bubbles of belief. We’ve also come to believe that these masters of business and the organizations they lead can bring us into the warmer glow of what’s good for us—and much of the rest of the world believes in this kind of progress too. Amazon brings us the near perfect shopping experience, Google a world of information at our fingertips, Uber a ride whenever we want one, Instagram pictures that capture what everyone is seeing, the Gates Foundation the end of disease as we know it…

In the process, we’ve also become a little (if not a lot) more individualist and entrepreneurial ourselves, with some of that mindset coming from the American frontier. We’re more likely to want to “go it alone” today, criticize those who lack the initiative to solve their own problems, be suspicious of the government’s helping hand, and turn away from the hard work of building communities that can problem-solve together. In the meantime, Silicon Valley billionaires will attend to the social ills we are no longer able to address through the political process with their insight and genius.

In this entrepreneurial age, has politics become little more than a self-serving proposition that gives us tax breaks and deregulation or is it still a viable way to pursue “what all of us want and need” in order to thrive in a democratic society?

Should we meet our daily challenges by emulating our tech titans while allowing them to improve our lives in the ways they see fit, or should we instead be strengthening our communities and solving a different set of problems that we all share together?

In many ways, the quality of our lives and our work in the future depends on the answer to these questions, and I’ve been reading two books this week that approach them from different angles, one that came out last year (“Earning the Rockies: How Geography Shapes America’s Role in the World” by Robert D. Kaplan ) and the other a few weeks ago (“Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World” by Anand Giridharadas). I recommend both of them.

There are too many pleasures in Kaplan’s “Earning the Rockies” to do justice to them here, but he makes a couple of observations that provide a useful frame for looking into our future as Americans. As a boy, Kaplan traveled across the continent with his dad and gained an appreciation for the sheer volume of this land and how it formed the American people that has driven his commentary ever since. In 2015, he took that road trip again, and these observations follow what he saw between the East (where he got in his car) and the West (when his trip was done):

Frontiers [like America’s] test ideologies like nothing else. There is no time for the theoretical. That, ultimately, is why America has not been friendly to communism, fascism, or other, more benign forms of utopianism. Idealized concepts have rarely taken firm root in America and so intellectuals have had to look to Europe for inspiration. People here are too busy making money—an extension, of course, of the frontier ethos, with its emphasis on practical initiative…[A]long this icy, unforgiving frontier, the Enlightenment encountered reality and was ground down to an applied wisdom of ‘commonsense’ and ‘self evidence.’ In Europe an ideal could be beautiful or liberating all on its own, in frontier America it first had to show measurable results.

[A]ll across America I rarely hear anyone discussing politics per se, even as CNN and Fox News blare on monitors above the racks of whisky bottles at the local bar…An essay on the online magazine Politico captured the same mood that I found on the same day in April, 2015 that the United States initiated an historic nuclear accord with Iran, the reporter could not find a single person at an Indianapolis mall who knew about it or cared much…This is all in marked contrast to Massachusetts where I live, cluttered with fine restaurants where New Yorkers who own second homes regularly discuss national and foreign issues….Americans [between the coasts] don’t want another 9/11 and they don’t want another Iraq War. It may be no more complex than that. Their Jacksonian tradition means they expect the government to keep them safe and hunt down and kill anyone who threatens their safety…Inside these extremes, don’t bother them with details.

Moreover, practical individualism that’s more concerned about living day to day than in making a pie-in-the-sky world is not just in the vast fly-over parts of America, but also well-represented on the coasts and (at least according to this map) in as much as half of Florida.

What do Kaplan’s heartland Americans think of entrepreneurs with their visions of social responsibility who also have the practical airs of frontier-conquering individualism?

What do the coastal elites who are farther from that frontier and more inclined towards ideologies for changing the world think about these technocrats, their companies and their solutions to our problems?

What should any of us think about these Silicon Valley pathfinders and their insistence on using their wealth and awesome technologies to “do good” for all of our sakes–even though we’ve never asked them to?

Who should be making our brave new world, us or them?

These tech chieftans and their increasingly dominant companies all live in their own self-serving bubbles according to Giridharadas in “Winners Take All.” (The quotes below are from an interview he gave about it last summer and an online book review that appeared in Knowdedge@Wharton this week).

Giridharadas first delivered his critique a couple of years ago when he spoke as a fellow at the Aspen Institute, a regular gathering of the America’s intellectual elite. He argued that these technology companies believe that all the world’s problems can be solved by their entrepreneurial brand of “corporate social responsibility,” and that their zeal for their brands and for those they want to help can be a “win-win” for both. In other words, what’s good for Facebook (Google, Amazon, Twitter, Uber, AirBnB, etc.) is also good for everyone else. The problem, said Giridharadas in his interview, is that while these companies are always taking credit for the efficiencies and other benefits they have brought, they take no responsibility whatsoever for the harms:

Mark Zuckerberg talks all the time about changing the world. He seldom calls Facebook a company — he calls it a “community.” They do these things like trying to figure out how to fly drones over Africa and beam free internet to people. And in various other ways, they talk about themselves as building the new commons of the 20th century. What all that does is create this moral glow. And under the haze created by that glow, they’re able to create a probable monopoly that has harmed the most sacred thing in America, which is our electoral process, while gutting the other most sacred thing in America, our free press.

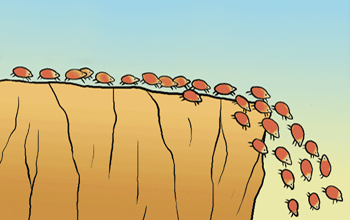

Other harms pit our interests against theirs, even when we don’t fully realize it. Unlike a democratic government that is charged with serving every citizen’s interest, “these platform monopolists allow everyone to be part of their platform but reap the majority of benefits for themselves, and make major decisions without input from those it will affect.” According to Giridharadas, the tech giants are essentially “Leviathan princes” who treat their users like so many “medieval peasants.”

In their exercise of corporate social responsibility, there is also a mismatch between the solutions that the tech entrepreneurs can and want to bring and the problems we have that need to be solved. “Tending to the public welfare is not an efficiency problem,” Giridharadas says in his interview. “The work of governing a society is tending to everybody. It’s figuring out universal rules and norms and programs that express the value of the whole and take care of the common welfare.” By contrast, the tech industry sees the world more narrowly. For example, the fake news controversy lead Facebook not to a comprehensive solution for providing reliable informtion but to what Giridharadas calls “the Trying-to-Solve-the-Problem-with-the-Tools-that-Caused-It” quandary.

Notwithstanding these realities, ambitious corporate philanthropy provides the tech giants with useful cover—a rationale for us “liking” them however much they are also causing us harm. Giridharadas describes their two-step like this:

What I started to realize was that giving had become the wingman of taking. Generosity had become the wingman of injustice. “Changing the world” had become the wingman of rigging the system…[L]ook at Andrew Carnegie’s essay “Wealth”. We’re now living in a world created by the intellectual framework he laid out: extreme taking, followed by and justified by extreme giving.

Ironically, the heroic model of the benevolent entrepreneur is sustained by our comfort with elites “who always seem to know better” on the right and left coasts of America and with rugged individualists who have managed to make the most money in America’s heartland. These leaders and their companies combine utopian visions based on business efficiency with the aura of success that comes with creating opportunities on the technological frontier. Unfortunately, their approach to social change also tends to undermine the political debate that is necessary for the many problems they are not attempting to solve.

In Giridharadas’ mind, there is no question that these social responsibility initiatives “crowd out the public sector, further reducing both its legitimacy and its efficacy, and replace civic goals with narrower concerns about efficiency and markets.” We get not only the Bezos, Musk or Gates vision of social progress but also the further sidelining of public institutions like Congress, and our state and local governments. A far better way to create the lives and work that we want in the future is by reinvigorating our politics.

* * *

Robert Kaplan took another hard look at the land that has sustained America’s spirit until now. Anand Giridharadas challenged the tech elites that are intent on solving our problems in ways that serve their own interests. One sees an opportunity, the other an obstacle to the future that they want. I don’t know exactly how the many threads exposed by these two books will come together and help us to confront the daunting array of challenges we are facing today, including environmental change, job loss through automation, and the failure to understand the harms from new technologies (like social media platforms, artificial intelligence and genetic engineering) before they start harming us. Still, I think at least two of their ideas will be critical in the days ahead.

The first is our need to be skeptical of the bubbles that limit every elites’ perspective, becoming more knowledgeable as individuals and citizens about the problems we face and their possible solutions. It is resisting the temptation to give over that basic responsibility to people or companies that keep telling us they are smarter, wiser or more successful than we are and that all we have to do is to trust them given all of the wonderful things they are doing for us. We need to identify our shared dreams and figure out how to realize them instead of giving that job to somebody else.

The second idea involves harnessing America’s frontier spirit one more time. There is something about us “as a people” that is motivated by the pursuit of practical, one-foot-in-front-of–the-other objectives (instead of ideological ones) and that trusts in our ability to claim the future that we want. Given Kaplan’s insights and Giridharadas’ concerns, we need political problem-solving on the technological frontier in the same way that we once came together to tame the American West. It’s where rugged individualism joins forces with other Americans who are confronting similar challenges.

I hope that you’ll get an opportunity to dig into these books, that you enjoy them as much as I am, and that you’ll let me know what you think about them when you do.

This post was adapted from my October 21, 2018 newsletter.

The book cover for “We Fed An Island” shows Andres holding a huge spatula and looking like he’s cooking. During his interview, he admitted that he didn’t do much cooking in Puerto Rico because his ability to manage the ever-changing demands was far more critical, “So, yes, my team probably is joking on these photos, saying, OK, the only time you would really cook [is when your picture is being taken].” Instead, his abilities enabled others to lead once he had gathered the raw materials and secured the facilities where they could do so. (“I became the leader, “ he said. “But actually, we had 25,000 leaders.”) As he later wrote:

The book cover for “We Fed An Island” shows Andres holding a huge spatula and looking like he’s cooking. During his interview, he admitted that he didn’t do much cooking in Puerto Rico because his ability to manage the ever-changing demands was far more critical, “So, yes, my team probably is joking on these photos, saying, OK, the only time you would really cook [is when your picture is being taken].” Instead, his abilities enabled others to lead once he had gathered the raw materials and secured the facilities where they could do so. (“I became the leader, “ he said. “But actually, we had 25,000 leaders.”) As he later wrote: