Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve written about some of the better escapes I’ve been enjoying in posts about “shoe gaze” music and “gourmet cheeseburger” TV, but after having these experiences and telling others about them, I always return to the same place I briefly left behind.

It’s the every-day-to-day where we spend most of our lives—because even when we’re trying to escape it’s routines and foregone conclusions, its mono-tones and tastes, we still carry its most troubling baggage with us. (Have you ever noticed how little you can truly “get away” on vacation?)

So I’ve been wondering for years now about ways to eke more sustenance out of the familiar places we want to escape from while reducing their uneasiness.

The question gained greater-than-normal urgency when we sheltered in place during the pandemic. At the time I argued for establishing everyday rituals to conjure more satisfaction, even meaning, out of a meal or how we get up in the morning (Extra From the Ordinary). I also drew some comfort from seeing how others—like comedian Bo Burnham—not only coped but almost thrived during the isolation because he knew, from being a kind of outsider as a child, “how to turn an uncomfortable situation into comedy” (Why We Gravitate Towards the Work We Do).

Moreover, the bankrupting aspects of everyday life don’t have to be a problem we solve on our own or just with the aid of our immediate families. By expressing our intention to face a common fate together, so-called “intentional communities” that share religious or social convictions can elevate some of the day’s opportunities and relieve some of its burdens by enabling their adherents to approach them together (The Re-Purposing of Ancient Wisdoms).

That time my example was of a kind a modern, Benedictine-Rule-based monasticism. But even then, its high level of commitment to any community made its solution wobble a bit (particularly here in America) where we keep saying we value our freedom and independence far too much to subordinate ourselves to the tyranny of any group. Like Groucho Marx, I feared too many of us would rather be alone than join any club that would be willing to have us.

So if we can’t imagine the long-term community benefits that might come with sacrificing some of our short-term personal preferences, what else might offer a consistent path to less stressful “living and working” on a regular basis? This week—yet another one I found difficult to weather “with my chin up”—I’ve been wondering out loud about the following:

Is it possible to experience a blissful relief within the boring intervals between our occasional escapes?

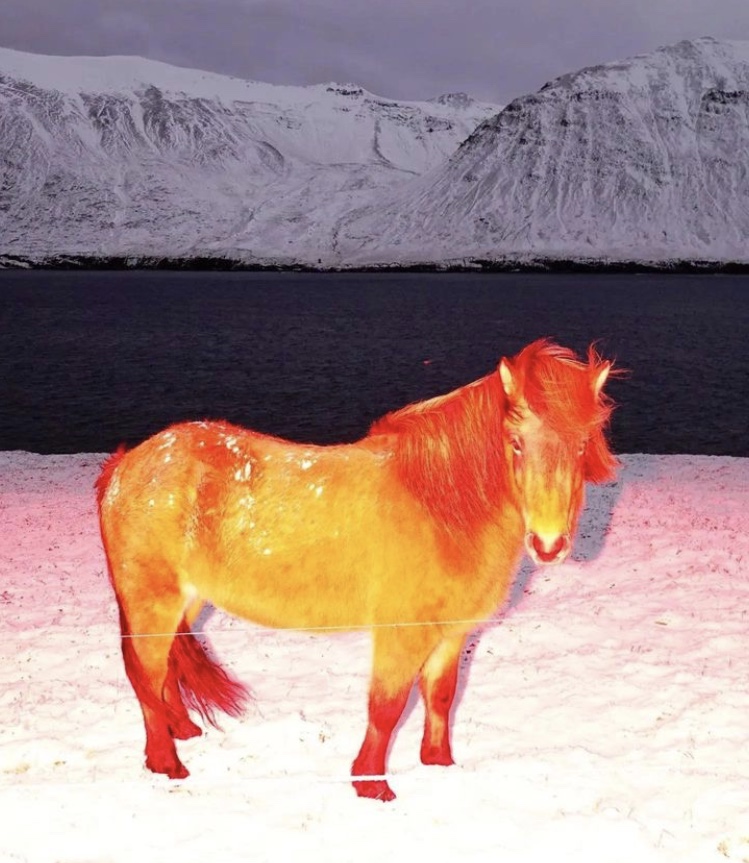

Pictured here (and up top) are different views of an “action sculpture” from 1999’s Wasser[or Water] installation Series by Swiss artist Roman Signer. As a boy, Signer dreamed of navigating white-water rivers and as an adult embarked on kayaking trips in remote mountainous areas until, one day, a companion of his failed to return with him. The kayak has been a recurring element in his work ever since. According to one commentator,“Wasserinstallation creates a vacuum where the beginning and the end of an imaginary journey converge.” You can explore more of Signer’s lifetime of visual artistry here.

When Robert Signer lost his kayaking companion, he tried to make sense of it, but when he found that he couldn’t he started creating what he called “action sculptures” to help him (along with those viewing them) go inside themselves, into a kind of meditative place, where instead of providing answers to impossible questions “meanings flow into one another effortlessly, without ever taking definite shape,” thereby offering a semblance of peace.

It’s akin to the facility that science-fiction writer and all-around-sage Ursula K. Le Guin was describing when she said once:

“To learn which questions are unanswerable, and not to answer them: this skill is most needful in times of stress and darkness.”

—in other words, in times like we’re in today.

Why has another child needlessly been killed in a refugee boat, border war or neglectful home?

Why did the flood sweep away this family or that village?

Why do the venal and wicked always seem to triumph over the honest and virtuous?

Why did my kayaking companion fail to return, but I did?

Then I asked:

How can we learn to sit with questions like these without sadness or remorse, anxiety or recrimination?

Where in our lives and work would finding relief from these gnawing discomforts be possible?

Could it be within our least engaging and most boring activities every day?

Well, that’s exactly what Justin McDaniel wanted me to believe. He’s the Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and (to my surprise) he’s been thinking and teaching others about the liberating effects of boredom for more than 20 years. McDaniel talked about the theory and his own experience testing it out on a podcast that I listened to this week.

I wouldn’t have thought of boredom—and in particular doing the kinds of things that we associate with it—as an escape hatch “from stress and darkness,” but for some reason I started playing closer attention as he started to explore the linguistic roots of the word “boring.”

The word’s root is “to bore,” of course, like putting a hole in a container and (by doing so) “rendering it useless” because it can no longer hold what it was intended to hold. In other words, it’s still a vessel, just not one that can also do something else, like hold water. In much the same way, many of our daily activities are similarly without much broader “use,” particularly when we refuse to fill them with some higher agenda, like “being more productive.”

When simply done “for their own sake” with no broader purpose, boring activities can be “incredibly liberating” according to McDaniel, allowing us to find simple relief in the task itself and not in what we’re getting done or producing. As a result, activities that are “boring” and effectively “useless” in this positive sense can trigger “a new beginning, a reset,” as he calls it, from the negativity that regularly weighs us down.

It’s a principle that’s been institutionalized for centuries by Buddhist monks in Southeast Asia where McDaniel studied as a student. Their days (and his) were consumed with tasks, repeated daily (like sweeping the same path or washing the day’s fruits and vegetables) that allowed them to empty their minds of everything beyond the task itself—like “boring a hole in yourself” and letting the extraneous out. Instead of aiming to do more, the point of boring/repetitive activities is actually to do less. In essence, McDaniel and the monks he was learning from found escape in boredom, or the repetitive monotony that characterizes many of our days too–at least when we refuse to compound the monotony with worry.

To somebody like me, who often feels overwhelmed by a 24/7 overload of “bad news” and my inability to absorb (let alone respond to) even a portion of it, hearing about an escape into boredom sounded like Relief. It was then that McDaniel started talking about how our brains “crave nothingness, crave non-productivity.” Stepping back from his remarks, I recalled making a similar point in a post from a couple years back called We Don’t Have to be Productive All the Time. But what McDaniel gestured towards was something that had been more elusive back then, namely, the potential cure that was offered by the non-productive activities that I perform all the time in the course of living and working.

It’s the every-day boredom of tasks at home: the cleaning, dressing, washing, eating, shopping, mowing the lawn, taking the dog out. It’s the daily boredom of tasks at work: research, writing, emailing, calling, meeting, promoting, monitoring information flows. All of these tasks have a repetitive monotony in them. To find their relief, I just need to strip them of their larger goals, objectives, the anxieties that I’m (somehow) not meeting them, and everything else I might be worrying about.

It really is like turning all the charging switches off while leaving the boring one on.

During his podcast appearance, McDaniel gave a beautiful illustration of this healing kind of boredom, and as he recounted it I realized he was talking about something he clearly does himself.

As a chaired professor at a prestigious university, his book-filled office likely hosts many “highly charged” but also “anxiety inducing” activities that could benefit greatly from the relief of a little boredom. For example, the students who visit it may want an “A” in his course, his endorsement for an internship, or a letter of recommendation that will flatter them when the time comes. As a professor, he might be hosting an ambitious colleague seeking tenure, a rival being competitive, or the professional pressure to do more impactful research himself. What all of these purposeful acts have in common, said McDaniel, is “do, do, do.”

But at that point in the podcast, he tried to offer us the same view that he simultaneously has of the books on his office’s bookshelves. “Who cares what’s in them,” he exclaimed (without the reverence I might have expected from a scholar.) What I do sometimes is “just look at them, and all the variety of the colors on their covers.” At that point I realized, that’s exactly what Justin McDaniel can be found doing in his office sometimes, particularly when his brain “craves non-productivity” and all the “do, do, do” that’s around him needs “a reset.” In these intervals, hiis books don’t have the higher purpose of scholarship or greater wisdom but simply the boredom of covers with many colors.

To me, this everyday and always-available peace is not unlike what Roman Signer is also offering in another one of his kayak-related installations.

Good luck with the boredom this week! I’ll see you next Sunday.

This post was adapted from my October 8, 2023 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes I post the content from one of them here. You can subscribe (and not miss any) by leaving your email address in the column to the right.