Even with a death toll that now exceeds 1100 from the clothing factory collapse in Bangladesh, it is far from clear that consumers of “fast fashion” are pausing before they make a beeline for the cash registers. Sure they feel bad about what happened and don’t want to support sweatshops in unsafe factories—at least in theory. But when the trade-off is foregoing the trendy jeans or sweater that will make them look good, desire overwhelms hesitation every time for most shoppers. Two studies seem to prove it.

At least some of it is because the concrete trumps the abstract nearly every time. What does this shirt or those shorts that I’m holding in my hands have to do with a thousand deaths I can’t even imagine in someplace called Bangladesh? What we don’t know simply doesn’t “hurt us enough” to make us change our behavior.

Thinking about how work can be more fulfilling starts with your own work. Are you proud of how it’s done, of what it accomplishes? It’s thinking that gets us wondering about whether our own consumption of energy or food or “fast fashion” has a dehumanizing impact on other’s people’s work. (“Do unto others. . . .”) But our wondering will never be enough as long as the “dehumanizing effects” are just platitudes or abstractions at odds with our convenience, our vanity, or the thrill of a bargain. In other words, it takes more information.

It’s a fact that women are literally dying to make “fast fashion” in one place so that women in another place can enjoy it. Women comprise 90% of the workers making clothes in Bangladesh. No other industry in that country (or in many others) absorbs as many female workers with little education or skill. Poor women make, rich women take.

Per capita income in Bangladesh is currently $850, while in the clothing sector it is almost half that: $456 a year or $38 a month. Not surprisingly, the Rana Plaza factory collapse has prompted talk about raising the minimum wage in this sector, but even without better pay Bangladeshi women will continue to make these clothes for the simple fact that no other jobs are available. Most of these women left male-dominated villages, where they had few opportunities to support themselves, for seven days of work, 8 to 12 hours a day, at clothing factories in the cities. Still, they barely make enough to live.

This week, a Wall Street Journal article quotes one woman who was injured in the factory collapse:

Sometimes I have to borrow to get to the next payday. But in the village I’d have to starve.

No alternative, no living wage, but she went on to say:

I’ll go back to work as soon as I get better. Not all buildings will collapse.

The “fast fashion” industry is built on indentured servitude, not so different than slavery. That is what it is: with outlets at a mall near you.

There have been some changes this week, like Western retailers signing on to finance safety audits and to pull their work from factories that don’t pass them. However, real progress will only come when we (as consumers) are more aware of the harmful effects of our consumption. Like the drug trade, as long as there is unfettered demand the supply will continue, much as it is today.

The “fettering” of our demand begins with knowledge about the consequences of our actions. In one of the studies referenced above, it is not surprising that shoppers interested in more expensive items (better educated, with better jobs themselves?) were also better at imagining the consequences of their purchases, and willing to pay more for a “sweatshop free” label.

As Jedediah Purdy noted in For Common Things, it is essential for us to grasp the often complex interconnections between what we buy here and what happens over there. To do so, we need:

an educated imagination, able not only to understand general principles through local efforts, but also to perceive local events as they are caught up in much larger schemes of production, exchange, and political and economic power.

It’s not just simply “getting as much as possible of a good thing” like low prices, “when in fact we are choosing where and whom to sacrifice for it.”

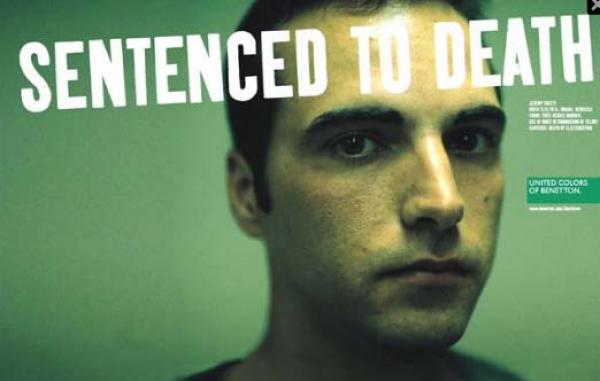

If understanding requires education, then maybe what the “fast fashion” retailers need to be doing is educating, both in their advertising (why I mentioned Benetton’s ads in my last post), and at the point of purchase. It could be pictures of women making clothes for other women. It could be pictures of women who died in 2013 making clothes like these. It could be asking shoppers: would you be willing to pay 10 cents more so that these women who are making your clothes could take home “a living wage”?

“Fast fashion” retailers need to start believing, as Sy Syms once said, that “an educated customer is our best customer.” Change in this industry will only come with improved customer knowledge.

Almost everyone can learn, when someone steps up to teach.