Our work impacts the world around us. It’s what we take from it, such as the raw materials or energy needed to produce our products or services. The work we do can benefit or burden our suppliers, our business partners, the community at large and the environment.

Our consumption of other people’s products and services also affects the world around us—although these impacts are harder to appreciate or take responsibility for. By buying their cotton shirts or bananas, sneakers or iPads, we sanction (tacitly and often unwittingly) what providers of our consumer products and services are taking or giving back in the course of providing us with the things we want.

Part of finding fulfillment in the work we do is being conscious of its various impacts, even proud of them. When our work is bringing the world closer to the way we think it should be, it accomplishes something important to us. What we do at work becomes part of a web of interconnections that is fitting, “as it should be,” from our vantage point.

When we’re thoughtful about the consequences of our own work, it becomes harder to ignore the impacts of the work that produces the things that we buy everyday. The recent factory collapse in Bangladesh that killed more than a 1000 people is a case in point. In the global marketplace where we shop today, we could all be wearing articles of clothing produced under dangerous conditions like this.

What responsibility do any of us have for the consequences of work that we support with our purchases—particularly when it all goes so terribly wrong?

Benetton is one retailer that kept their prices low in a highly competitive clothing market by making some of its garments in that devastated factory outside Dacca.

The factory Benetton used was a deathtrap like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York was a deathtrap. But when the Triangle Shirtwaist fire killed 146 garment workers in 1911, Americans responded to the carnage more out of kinship with the workers than because of anything they gained from the products that were being made there. It was empathy that fueled the rallying cry for worker safety a century ago.

Our forebears were “close enough” to see what this tragedy had to do with them and to understand what had gone so terribly wrong. It was their proximity, the smell of death and familiarity with faces that drove the efforts at reform that followed.

Half a world and a cultural divide away in Bangladesh, it is not so much the abstraction of their shared humanity that ties us to the victims in this collapsed factory, but the fact that the clothes they made were ending up on shelves at a mall near you. This is the overlap of their lives on ours that helps us to internalize the impact of their deaths. Wendell Berry describes the emotional calculus this way:

To hear of a thousand deaths in war is terrible, and we ‘know’ that it is. But as it registers on our hearts, it is not more terrible than one death fully imagined.

These clothes that we know and could have purchased are what tie our imaginations to those who died producing them. If ours (and Benetton’s) endless pursuit of “lower prices” contributed to the tragedy, what should any of us do about it?

It is often difficult enough to comprehend the impacts of our own work, let alone the far-flung impacts of the work that others do to produce all the things we consume. (Did slave laborers pick your bananas? Did children make your sneakers? Is your diamond ring financing brutality in a conflict zone?) The drive for more localized supply chains and to consume more local products comes, in part, from wanting to be close enough to their various impacts so that we are can “imagine” the consequences and make the responsible decisions that need to be made about them. Local is more comprehensible and manageable than global.

There are no easy answers here. But the difficulty of understanding the harsh realities around much of our consumption does not mean that we have no responsibility for them. This tragedy allows us to pause and consider what they should be.

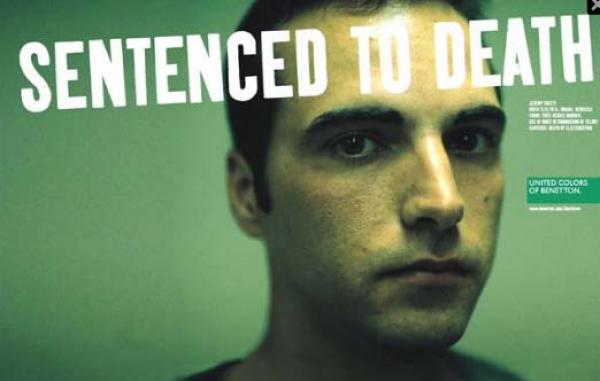

As for Benetton, it has announced that it will make funds available to aid the victims of this factory collapse. For a company that has long used provocative advertising to promote its views on conscience-tugging issues like racism and the death penalty, this is hardly surprising. What I’m waiting for is the Benetton ad that helps us to calculate the terrible costs that are being incurred so that consumers like us–a half a world away–can keep paying the lowest possible price.