Listening to myself tell you about something that happened in 5th Grade makes me feel like it was a hundred years ago, almost lost in the mists of time.

Either the weather was bad or there was some other reason that we couldn’t go outside for recess so our teacher—Sister Dennis I think her name was—needing some way to redirect our 10- or 11-year-old restlessness, asked if we’d like to hear her read us a story.

To call our muffled response a “Yes” that day would have been generous, but that’s what she chose to hear, having no better idea about “what to do with the lot of us” under the circumstances.

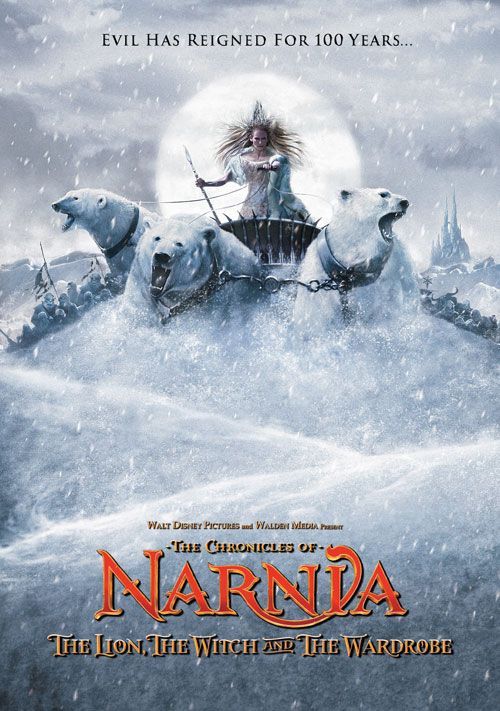

The book she’d selected was “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe” by C.S. Lewis. and this is how it begins:

ONCE there were four children whose names were Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy. This story is about something that happened to them when they were sent away from London during the war because of the air-raids.

That was really all it took to settle us down & put us on our way to finding out more about this refuge from the Blitz, the furtive games of hide & seek that took place there, and how one such game found Lucy (the youngest of the 4) hiding in a wardrobe that became a portal to a another world as she pushed her way inside and started feeling snow & ever-green branches instead of simply coats and sweaters.

Us 5th Graders ended up having the whole book read to us during that season of grade school because every time we couldn’t go outside (and even some times when we could) we called out for it in something like a chorus, not being able to wait any longer to hear what happened next as those children met the White Witch, a fearsome Lion and a taking faun named Mr. Tumnus.

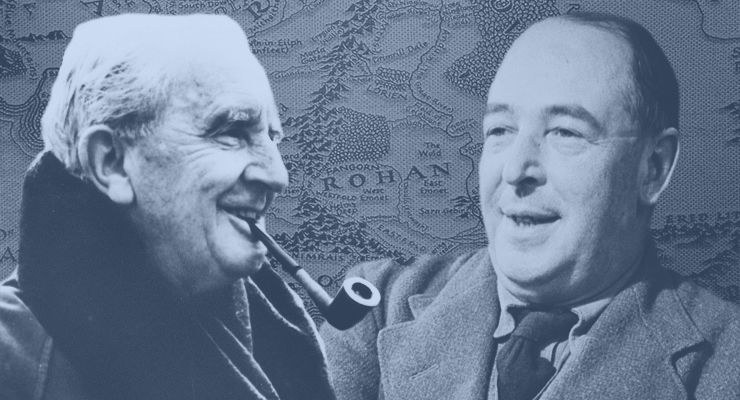

I mention all this because a new book came out recently about C.S. Lewis, his friend and Oxford University colleague J.R.R. Tolkien, and how both came to pen sagas about marvelous worlds that were more hopeful & noble & loyal than the worlds that had collided around them during World War II. This book is called “The War for Middle Earth,” and it begins with the fantasy world that Lewis called Narnia, a place “with endless winter and no spring,” and with an equally menacing one that Tolkien conjured out of hobbits, dwarves, humans & elves and their struggles to defeat the malevolent forces that had gathered around the Lord Of the Rings.

In “The War for Middle Earth,”author Joseph Locate’s main point is that both Lewis & Tolkien wanted to bring a broken world stories that were powerful enough to re-animate human virtues like wisdom & friendship, courage & self-sacrifice we seemed at risk of losing in our modern battles of Good versus Evil.

Both Lewis and Tolkien had fought in the Great War (1914-1918) and the experience had (in the words of one reviewer) “endowed them with a tragic sensibility and a perception of true heroism” instead of the “twin drugs of ideology and nihilism” that too many of their fellows had turned to in order to manage the pain of that barbaric conflict. Concerned that the second great war also saw too little virtue and “faith in human dignity,” Lewis came to write his Chronicles of Narnia (1950-56) and Tolkien his Lord of the Rings trilogy (1954-55). As this reviewer continued:

Much of Mr. Loconte’s history concerns Lewis’s and Tolkien’s efforts as scholars. Their positions in Oxford’s English department gave them authority to promote classic literature as a solution to modern discontent. Tolkien, a scholar of Old English, studied the ‘theory of courage’ found in poems such as the ancient epic ‘Beowulf,’ redeeming what he called the ‘noble northern spirit’ from the fascists who would pervert it. Lewis, meanwhile, sought to recover the ideas of love that animated medieval and Renaissance literature. Both authors admired the way that the medievals combined pagan virtues with Christian theology to sustain a culture that was simultaneously vital and humane.

Lewis & Tolkien believed that the West’s literary tradition provided the moral grounding that can enable individuals “in the face of death” to forsake their own safety in the struggle to save others from subjugation. In Loconte’s view, both hoped their imaginative stories would help to counter “many in the West” who had come to doubt and even resent our civilization’s ideals in their cynicism and retreat from what would have once been seen as necessary commitments. Arsenals like fellowship and a wider respect for human dignity would be necessary to counter new despots as they sought to spread their particular brands of tyranny.

In other words: What is still worth fighting for after all the darkness and horror they had seen?

What virtues will humanity need for its next battles?

“Evil has reigned for100 years.” What will we need to replace it?

Legions of orcs are one face of Evil in the battle for Middle Earth.

A couple of hundred posts ago, I wrote here about an exhibit at Oxford’s Bodieian Library of watercolors that Tolkien had painted before writing either “The Hobbit” or “The Lord of the Rings” so he could envision the world that his heroes would be fighting for. In that same newsletter, I quoted from a local philosophy professor who lamented the near-impossibility of imagining such an ideal world today—our “utopia of desire”—and what it would feel like to be returning there after the additional shocks the human race has experienced in the 80 years since Lewis & Tolkien had offered us their ways back home.

He despairingly told us:

The utopias of desire make little sense in a world overrun by cheap entertainment, unbridled consumerism and narcissistic behaviors The utopias of technology are less impressive that ever now that—after Hiroshima and Chernobyl—we are fully aware of the destructive potential of technology. Even the internet, perhaps the most recent candidate for technological optimism, turns out to have a number of potentially disastrous consequences, among them a widespread disregard for truth and objectivity, as well as an immense increase in the capacity for surveillance. The utopias of justice seem largely to have been eviscerated by 20th-century totalitarianism. After the Gulag Archipelago, the Khmer Rouge’s killing fields and the Cultural Revolution, these utopias seem both philosophically and politically dead.

That catalog of smashed ideals was compiled almost 8 years ago, before a global pandemic, growing political divisions, media’s assault on our attention spans, and the rise of artificial intelligence had defeated even more of our hopes.

So it’s fair to ask: how much more do we need collective stories—ones that affirm the best in humanity, show us how to have courage & conviction—in our current battles against nihilism & tyranny?

Such a story might begin with our visualizing what we cherish most about our lives. For Lewis & Tolkien, it was the communal life of the countryside and the heroism that everyday people could muster in challenging times. For both, it was also courageous action emboldened by faith.

In their respective writings, their challenge was to combine these elements into more compelling narratives than the fascists or communists had been telling. To that end, Lewis & Tolkien took what was best in the Western literary tradition and wove it into characters & plot lines that effectively “critiqued and opposed the point-blank threat of what was worst in our tradition,” as another reviewer has noted. These sagas “made qualities like courage and fortitude deeply attractive to an otherwise skeptical generation.”

Said Lewis himself: “When we have finished [these narratives], we return to our own life not relaxed, but fortified.”

The early-teen protagonists in the streaming saga “Stranger Things,” arrayed against the forces of Evil that treaten their hometown.

By now you’ve probably gathered that I wish every unexceptional inhabitant of this troubled planet could have the benefit of new stories & sagas that could bolster the fortitude and courage they’ll need in their current struggles against cynicism, despair and resignation.

How long has it been since a story you’ve read or watched actually left you emboldened or (as C.S.Lewis put it:) “fortified” instead of merely entertained?

Late last fall, I joined the daughter of close friends who was visiting from graduate school, we got to talking about stories we’d recently enjoyed, and she strongly recommended that I watch Season 3 of “Stranger Things,” an 80’s-inspired, sci-fi/horror-saga with large doses of comic relief about a close-knit group of small-town kids who play games like Dungeons & Dragons far from the in-crowd of their middle school before mustering their talents to confront the ultimate Evil.

The recommendation came with certain demands, like watching the first 2 seasons of the show to get to know the characters and their fight against the horrors of the mirror world that exists beneath them as well as a federal government that aims to harness its potent powers. Well I took her advice, made it through the Season,1, marveled at the uptick of Season 2, and was (as promised) amply rewarded by the remarkable confrontations of Season 3.

The story profiles young heroes in impossible situations while their adolescent hormones intrude & shows their self-sacrifice and courage in genuinely terrifying circumstances, all while celebrating (in technicolor) the aspects of their town (the mall & community pool, annual fair & middle-school dance) that they love the most and rally to protect.

The Duffer Brothers behind “Stranger Things” are not C.S.Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, but what they built in this multi-dimensional & deeply human saga about a more “contemporary” battle between Good & Evil is noteworthy, and their success as storytellers in the storytelling marketplace even more so.

The entire 5 season franchise has gotten more than 1.2 billion views. It has become a global cultural phenomenon for younger generations that have lived much of their lives during the Great Recession, a global pandemic, through the downsides of cellphones and social media & amidst their ever growing fears about the future. If the show’s fans were looking for heroes who embodied loyalty & bravery against impossible odds they would have found them in Season 3—several of them in fact.

So if “Stranger Things” demonstrates anything, it is the ravenous hunger that young viewers have for stories that might help them cope with the daunting array of challenges they’re facing on a daily basis.

And while the show will likely be less fortifying for anyone over 30, I found Season 3 to be a sometimes unnerving, sometimes hilarious & often heart-rending thrill ride through some of my best memories of the 1980’s, all delivered with the soundtrack, hair, clothes, cars & destinations that made it a slice of America that actually may be worth fighting & dying for.

“Stranger Things” is not quite the successor to the Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings, but it demonstrates our burning desire for a story that can help us prevail in what is far too often a horrifying & dismaying world,

This post was adapted from my February 1, 2026 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes I post the content from one of them here, in lightly edited form. You can subscribe by leaving your email address in the column to the right.