I’m not afraid of poetry, but I don’t read it as often as I should. Somebody mentioned What Work Is, a poemby Philip Levine on the radio today.

I read it, then heard him read it, then wanted to share it with you for what it has to say about the work we do. Here it is:

We stand in the rain in a long line

waiting at Ford Highland Park. For work.

You know what work is–if you’re

old enough to read this you know what

work is, although you may not do it.

Forget you. This is about waiting,

shifting from one foot to another.

Feeling the light rain falling like mist

into your hair, blurring your vision

until you think you see your own brother

ahead of you, maybe ten places.

You rub your glasses with your fingers,

and of course it’s someone else’s brother,

narrower across the shoulders than

yours but with the same sad slouch, the grin

that does not hide the stubbornness,

the sad refusal to give in to

rain, to the hours wasted waiting,

to the knowledge that somewhere ahead

a man is waiting who will say, “No,

we’re not hiring today,” for any

reason he wants. You love your brother,

now suddenly you can hardly stand

the love flooding you for your brother,

who’s not beside you or behind or

ahead because he’s home trying to

sleep off a miserable night shift

at Cadillac so he can get up

before noon to study his German.

Works eight hours a night so he can sing

Wagner, the opera you hate most,

the worst music ever invented.

How long has it been since you told him

you loved him, held his wide shoulders,

opened your eyes wide and said those words,

and maybe kissed his cheek? You’ve never

done something so simple, so obvious,

not because you’re too young or too dumb,

not because you’re jealous or even mean

or incapable of crying in

the presence of another man, no,

just because you don’t know what work is.

You can also hear Philip Levine introduce his poem and then read it.

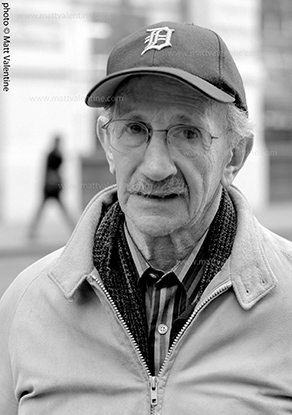

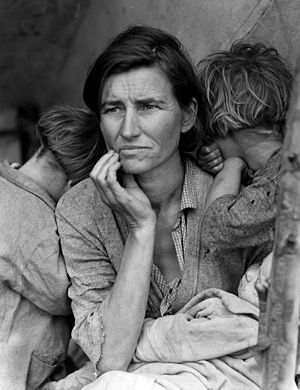

Levine is a Pulitzer prize-winning American poet, who is currently the poet laureate of the United States. He frequently writes about life in working class Detroit. His life story left me thinking about a different era in American life, of dustbowls and Woodie Guthrie and photographs by Dorothea Lange. About waiting for work and the opportunity to be productive.

We are in our own hard times. There is no less nobility in the work that we’re doing, and waiting to do.