We all like feeling rewarded for work that makes things better. Many of us are finding this kind of satisfaction in social benefit games. At the same time, we’re also learning how to bring transformative change into the world by getting some practice first.

Your rewards include feeling good about yourself because of all you’re accomplishing and the abilities you’re developing while doing so. In social games like WeTopia, you reap other rewards too. There is pride in the growing productivity of your community, empowerment from your ability to support those in need, and your own increasing prosperity.

Games like this also bring the best ingredients of the for-profit and non-profit worlds together.

They give you the virtual experience of work where you can do well by doing good. They stir your imagination, and get you thinking about new kinds of work that you could be doing right now in the real world.

On the other hand, it’s disquieting to feel that someone is “behind our screens” watching us and gaining insights about human behavior because of how you, me (and millions like us) are playing these games. These social scientists and marketers are looking at how we respond to different sounds, colors and kinds of movement. They are even changing the variables we encounter in these games while we’re playing them to see if we do things differently or faster or better.

What’s going on here, and where is the upside for us in this kind of scrutiny?

Kristian Segerstrale is an economist and co-founder of a company called Playfish that makes on-line games. In an interview, he described the difficulty social scientists have traditionally had gaining reliable information from behavioral experiments because they can’t control the variables that exist in the real world. By contrast, in virtual worlds:

the data set is perfect. You know every data point with absolute certainty. In social networks you even know who the people are. You can slice and dice by gender, by age, by anything.

Segerstrale gave the following by way of example. If your on-line experience requires buying something, what happens to demand if you add a 5 percent tax to a product? What if you apply a 5 percent tax to one half of a group and a 7 percent tax to the other half? “You can conduct any experiment you want,” he says. “You might discover that women over 35 have a higher tolerance to a tax than males aged 15 to 20—stuff that’s just not possible to discover in the real world.”

What this means is that people who want to sell you things or motivate you to do something are now able to learn more than they have ever been able to learn before about what is likely to influence your behavior.

Being treated like ingredients to be “sliced and diced” has risks for us, but also possibilities.

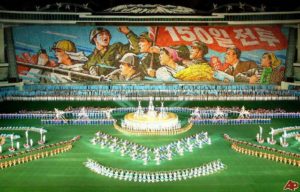

None of us want to relinquish our freedom and become automatons, manipulated into doing what others want us to do. We do well to remember national experiments in social engineering, like the tragedy of the Cultural Revolution in China and the choreographed death spiral in North Korea.

But we also need to recognize the potential in this brave new world for good.

The behavior of millions of men and women whose voices had never been heard before was changed by lessons learned on-line, ultimately producing the Arab Spring.

The behavior of individuals facing repression every day in places like Iran and Syria is fortified by the virtual support of those who are struggling with them.

Your behavior, and the behavior of millions of people who are playing these social games, is being shaped and reinforced in similar ways. It is a training ground for changing the real world with new and better kinds of work.

Social benefit games are giving us a recipe for transformation—and the ingredients are getting better all the time.

But most of the venting missed the truly provocative question Keegan was asking: for those in her generation who want to make a difference in the world, how can you get a job that will enable you to start doing so?

But most of the venting missed the truly provocative question Keegan was asking: for those in her generation who want to make a difference in the world, how can you get a job that will enable you to start doing so?