When we change our routines in a fundamental way—either because we need that change or the interruption is foisted upon us—we sometimes experience our world differently when we return.

Glimpses of those differences are possible after vacations, but they usually need to be long enough and far enough away. These differences in perspective also need to become realizations: our conscious efforts “to capture” what our time away “was really about” and consider its impacts “on what we do next.” At this point, the contrast between before and after might be bold enough to change our outlook going forward—like eat more pasta or dance everyday—but these realizations seldom change the basics about our living, our working or how we think about them. They’re more like souvenirs.

Clearer and longer breaks between departure and return generally have a greater impact because there’s more time to ponder the differences between this new place and the one we left behind. When we return to where we started, we are able to compare how it seemed before with how it seems to us now in light of the new perspectives that we’ve gained. As a result of these realizations, we sometimes do change our basic routines or broaden our rationales for doing them.

Insights about what-came-before, what-came-next and now-that-you’re-back can be even more profound if your physical or mental abilities changed during this interval. For example, you needed a new environment because you were injured in some way or found yourself facing an unfamiliar limitation. Only after time-away were you healed enough to return to the world you had left behind. Your judgments can be more nuanced when the changes to your body or spirit have also sharpened your awareness of where you’ve been and where you find yourself now.

Insights about before, next and now might be sharper still if changes in your perceptual abilities were behind your initial departure. If, say, you’d been partially blinded and had to rely on the heightened senses that remained to “map” the new environment where you retreated and the old one that you returned to “with new eyes.”

Finally, your insights might be at their sharpest and most valuable if the world you left had also changed in some fundamental way in the months or years before your return. The heightened awareness that you gained while away would be encountering this new topography for the first time. It is this final vantage point that Howard Axelrod brings to his new book, The Stars in Our Pockets: Getting Lost and Sometimes Found in the Digital Age.

Axelrod’s short story is that he was accidentally blinded in one eye during a college basketball game, took the next 5 years to graduate and recover physically, and spent the two years that followed living off the grid and reorienting himself with his natural environment in the woods of northeastern Vermont. After his time away, he began a teaching career at two urban universities.

Between his partial loss of sight and his return to civilization, smartphones had not only become ubiquitous, but in startling contrast to his back-woods life, these “stars in our pockets” seemed to be changing “how we navigated the world” right in front of him. It was an insight that might not have been possible if the contrasts between the world he’d departed, the one he retreated to and the one he re-entered had been less stark, or the realizations that he took from his experiences had been less acute.

In the “cognitive environment” of northern Vermont, Axelrod deepened his sense perceptions, made lucky discoveries as he wandered in the outdoors, and cultivated a sense of curiosity and patience that had been commonplace for much of human history. He learned to pay attention to the weather, the seasonal changes, the time of day, the life of the forest around him, and realized that doing so reinforced a particular kind of “mental map” that enabled his understanding of the world and how he could find his way through it. When Axelrod returned to urban life, he realized that the smartphones people were now holding as they walked down the street or sat across from one another at lunch were changing how almost everyone—including him—understood and experienced the world. In other words, the mental map that a smartphone enables is fundamentally different from the mental map he’d been using to navigate during his time off the grid.

The message in Axelrod’s book is not that one map is better than the other. His writing is more “meditation” (as he calls it) than argument or indictment. Instead, he wants to highlight some of the complications that can arise when you alternate between how humans have always navigated their lives and work and the new ways of doing so that mediating devices like our smartphones have enabled. In a recent interview and from postings on his website, Axelrod wants to convey what happens when adapting to a new environment means “losing traits that you valued” in your first one.

Just as we’re losing diversity of plant and animal species due to the environmental crisis, so too are we losing the diversity and range of our minds due to changes in our cognitive environment.

Several of these losses are worth our noticing with him. For example,:

–Tech tools may replace natural aptitudes and weaken the memories that they depend upon. Axelrod suggests that relying on GPS to navigate undermines not only the serendipity that often comes “when you’re finding your own way,” but also your reliance on innate navigational memories so that you don’t get lost. Axelrod says:

Our memory is tied inextricably to place. In our brains, the memory center, the hippocampus, is the same center for cognitive mapping — figuring out the route you’re going to take. If we’re no longer using our brains to navigate [and] coming up with these cognitive maps, studies show that we start to have problems with other kinds of memory.

–External prompts change our attention spans. As we grow more accustomed to on-line suggestions before taking the next step, autonomous actions—including immersing yourself in an activity and entering into what psychologists call productive “flow states”—become more difficult.

What [American philosopher William] James [once] said is that an attention span is made of curiosity. It’s the ability to ask subtly different questions. Whether you’re talking about intellectual attention, or sensorial attention, if you’re looking at a tree or watching a bird. Are you asking subtly different questions? Can you ask a question about one facet and then another? It feels like you’re paying attention steadily, but you’re really paying attention to a lot of different things, driven by your curiosity.

Online, there’s always something prompting your attention. It’s like a pseudo-curiosity. It comes in and will give you the next thing to purchase, the next article to read, the next video clip to watch. You don’t have to ask the next question — it’s provided for you. Your attention span will shorten because you don’t need to ask those questions, you don’t need to drive your own attention.

–Rapid-fire “likes” on-line also requires much less involvement from us than empathy requires off-line. Axelrod notes how disorienting it can be as we shuttle between our tech-enabled environments and the rest of our lives and work, where we often need to come to what he describes as “slower” understandings of one another:

[W]hen you’re on social media, part of what’s being called for is attention that can shift really rapidly from one post to another post. And also what’s being called for is a kind of judgment: Do you like this? Do you love this? Do you retweet this? Whereas in real life, what’s called for is a slower attention, where you’re able to listen, be patient while the person is pausing, thinking, not quite sure what they’re saying. And also what’s called for is to defer judgment, or not judge at all. To have empathy. Those are very different traits, depending on which environment you’re in.

–It is hard to reconcile or internalize the different, competing ways that we use to navigate our on-line and off-line realities. Moreover, the world we experience behind the screen can become a substitute for (or even replace) the frameworks that come from navigating in the off-line world. What we risk losing, says Axelrod, are:

our connection to something larger than ourselves, our sense of perspective, our sense of what came before us or what will come after, our sense of being a part of the natural world — that doesn’t really show up anywhere on the maps on our phones.

As we adapt to a virtual world, we’re often disoriented because its cognitive maps are so different and “we’re effectively living in two places at once.” But our adaptations change how our minds work too. In what Axelrod calls “neural Darwinism,” a kind of “natural selection” also happens “on both sides of your eyes” as we adapt to living and working through our screens. “[C]ertain populations of neurons get selected and their connections grow stronger, while others go the way of the dodo bird.” In other words, the faculties that we exercise on-line grow stronger, while those from the off-line world that we rely upon less frequently weaken from disuse.

These losses are tangible: Remembering how to navigate the world without on-line short-cuts. The longer attention spans that we need for concentration. The slower attention spans we need for empathy. Perspectives that extend from the past and into the future. Feelings that we are a part of the natural world.

Our smartphones and other virtual companions are changing our capabilities in each of these ways, but like that frog in water coming to a slow boil, too many of us may be lulled into complacency by the warmth of their star-power.

Axelrod returned from the Vermont woods when the rest of us were already caught up in their magic. With the heightened sense of being human that came from his own particular odyssey, he could see more clearly not only what we’d been gaining while he was away but also might be losing as we gradually moved off our old navigational maps and started our pell-mell quest to adapt to very different ones.

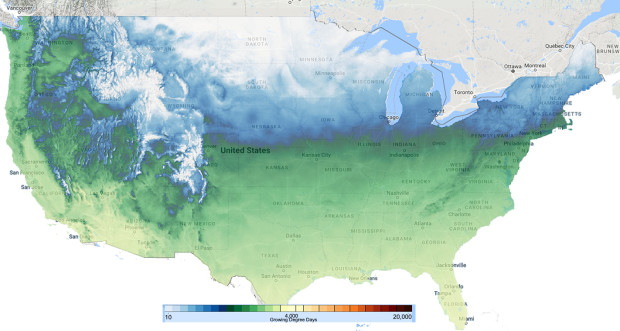

The map at the top of this post illustrates how navigation, weather, visibility, air pollution—a dozen different variables—might change in light of the fires that have recently burned through much of the western US. A poor attempt at metaphor (perhaps), but many of the fires on this map also originated in northern California, where many of the technologies behind our smartphones originated.

These “stars in our pockets” with their shortcuts, search engines and diversions are causing us to adapt to the navigational demands of an entirely new environment, where the potential costs of doing so include the loss of deep-seated memory, the ability to make our own choices, and discomfort with the “slow art” of interacting with others. Because we don’t exercise these aptitudes when navigating our new mental maps, we risk losing them as we attempt to navigate the old maps of our parallel, off-line worlds.

In a December post, I shared Tristan Harris’s theory that our brains may simply not be able to handle the challenges posed by these tech-driven interfaces. Harris went on to argue that the overwhelming information they provide also produces a kind of learned helplessness in us that’s not so different from where the frog, coming to a slow boil, finds herself.

The trick, I think, is making a deliberate effort to exercise the human capabilities that enabled us to navigate the world before these awesome devices came along—not letting them atrophy—even if we have to spend some equivalent of Howard Axelrod’s time in the northern Vermont woods to come to that realization.

We may need the sharpness, the clarity, of something like his departure and return to notice that much seems to be going awry before we resolve to do something about it.

This post was adapted from my February 2, 2020 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning and the contents of some of them are later posted here. If you’d like to receive a weekly newsletter, you can subscribe by leaving your email address in the column to the right.