Some days it’s good to be reminded.

I saw the aftermath of a terrible car and motorcycle accident a few days ago, and couldn’t help being caught in its blast radius because its impact reverberated almost to my doorstep.

From the epicenter, I heard the wailing of civilian rescuers huddled over what was surely the rider, the motorcycle he’d been on strewn in pieces a few feet away. Several cars had stopped already and knots of onlookers were clustered at the intersection’s nearest corners.

Traffic had backed up for much of the very long block and was throbbing to break through. One neighbor or pedestrian wearing a bright green shirt took to the center of the street, not embodying “Go” but shouting just the opposite: “You’ll have to turn around,” as one car defiantly entered the empty, opposing lane to push through his impatience. “Really,” the Green Man countered, “are you in such a hurry that you’re willing to risk more injuries?”

At their confrontation I thought of going back inside, but feeling his protectiveness too I strained for a look at the aura of assistance that was closer in than this spontaneous traffic monitor who was bravely putting himself between his own safety and more cars that were feinting to get through.

Just then, an equally improvised town crier–perhaps sensing the ambivalence of our sympathies– shouted: “It was an illegal turn, the motorcycle was not at fault” because she too may have been assuming that it was. In the murmuring that followed, it also became clear that the illegal turner had fled the scene, which made the witnesses and passers-by seem to move even closer in, as if to shelter the body that had been left alone in the middle of two city streets. Surely, it wasn’t just moth-to-flame interest that held us here. I tried to gather my vaguer explanations before another driver tried to power through the threads and associations or the sirens arrived.

They ended up converging on what Fred Rogers had said one day to a kid who regularly visited his Neighborhood:

When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’

Some years ago I’d been in the middle of a different accident when I hit a dog who’d run into the road and a whirlwind of help, rubbernecking and road rage had spun around me as I cradled that dog in the middle of an even crazier intersection. It added up to one of my worst and best days for many of these same reasons. I can still feel strangers hovering over me, trying to hold back the traffic like a gathering storm, helping.

People help because it allows them to draw on their ability to act–that is, to take matters into their own capable hands–before “experts,” like the police, the ambulance crews, the tow truck drivers who have been on the lookout for wreckage, show up. It’s also acting on the common bond they feel with the fallen, maybe remembering when a stranger had helped them or sensing an as-yet unrealized potential to intervene in the same way themselves.

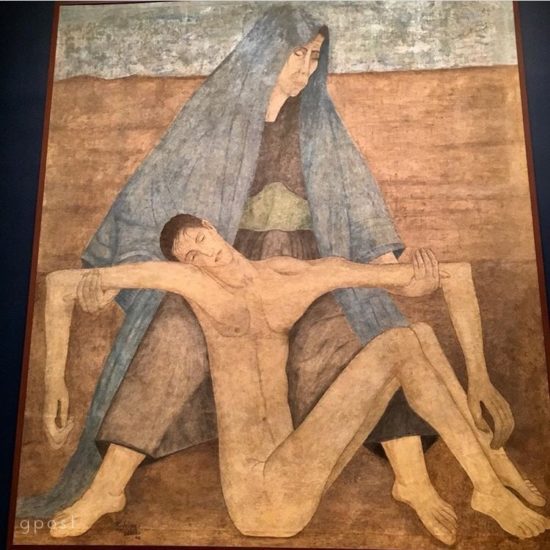

During days like today when selfish and mean can seem front and center, there’s always hope to be found in the helpers. I, for one, never trust that they’ll come, but they still, always seem to. It’s the surprise of grace. And they were there again this week, gathering around a body that had been hit and broken before it was abandoned.

Fortunately, fatefully, these expressions of shared humanity are everywhere when we look for them, from the most extreme circumstances to the most mundane. Writer Rebecca Solnit described “improvisational communities of help” around earthquakes like the tremor that destroyed much of San Francisco more than a century ago, hurricanes like Katrina that ravaged New Orleans, and the terrorist attack on 9/11 in New York City. A half a year ago, I wrote about a helping community that materialized in a Walmart parking lot after a terrible fire had nearly obliterated a place that could no longer be called Paradise California without shaking your head.

In a new article, Yale sociologist and physician Nicholas Christakis has created “a record for analysis” out of the information that still exists about survivors of shipwrecks over a period of 400 years (from 1500 to 1900), drawing tentative conclusions about their post-wreckage collaborations and potentially opening up new ways of assembling “data sources” for testing by social scientists.

In today’s post, there is more on Solnit’s observations about human nature and Christakis’ thoughts about cooperative behavior after tragedy.

Tracking on Christakis’ research, the pictures here are of turbulent seas and the inevitable shipwrecks, all by perhaps England’s greatest painter, J.M.W. Turner. Each one invites us to imagine what comes next and to be continuously surprised by how good that can be.

1. Spontaneous Helping Communities

Rebecca Solnit’s A Paradise Built in Hell: the Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster alerted me to how average people became rescuers during several of the worst catastrophes in American history. She explains it, in part, by how “diving in to help” brings a sense of confidence and liberation that is lacking in people’s private lives. For these civilian rescuers, it’s almost experienced as enjoyment:

…if enjoyment is the right word for that sense of immersion in the moment and solidarity with others caused by the rupture in everyday life, an emotion graver than happiness but deeply positive. We don’t even have a language for that emotion, in which the wonderful comes wrapped in the terrible, joy in sorrow, courage in fear. We cannot welcome disaster, but we can value the responses, both practical and psychological….The desires and possibilities awakened are so powerful they shine even from wreckage, carnage, and ashes.

It’s as if we can see better versions of ourselves as leaders, problem-solvers, caring adults and members of a flesh-and-blood communities shining through.

Speaking with any assurance “about life today” is always risky, but it does seem that we exalt “minding your own business” as an excuse today for not getting more involved while building as much insulation as we can afford between our private and public lives. It may explain low voter turn-out, general political apathy and cynicism, our involvement with arms-length communities (like Facebook) instead of real ones where we have to get our hands dirty and look our neighbors in the eye, and the time we spend in echo-chambers that reinforce our sense of “us vs. them” But at exactly the same time that our private lives seem paramount, Solnit’s argument is that we also crave more meaningful engagement than we’ll ever find living behind safety glass.

It is this longing that has a chance to be satisfied when regular people find themselves helping during a car accident or other emergency. We suddenly feel more fully alive than we felt before. Solnit analogizes the fullness that regular people feel under these circumstances to the solidarity and immediacy that soldiers often experience during wartime.

We have, most of us, a deep desire for this democratic public life, for a voice, for membership, for purpose and meaning that cannot be only personal. We want larger selves and a larger world. It is part of the seduction of war William James warned against—for life during wartime often serves to bring people into this sense of common cause, sacrifice, absorption in something larger. Chris Hedges inveighed against it too, in his book War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning: ‘The enduring attraction of war is this: Even with its destruction and carnage it can give us what we long for in life. It can give us purpose, meaning, a reason for living. Only when we are in the midst of conflict does the shallowness and vapidity of our lives become apparent. Trivia dominates our conversations and increasingly our airwaves. And war is an enticing elixir. It gives us resolve, a cause. It allows us to be noble.’ Which only brings us back to James’s question: What is the moral equivalent of war—not the equivalent of its carnage, its xenophobias, its savagery—but its urgency, its meaning, its solidarity?

The clutch of men and women kneeling over and attending to the victim sprawled on the intersection near my front door were finding it.

It’s why the Green Man turned himself into a traffic cop right before my eyes. He was finding something that he needed too.

2. How Shipwrecked Survivors Came Together Time After Time

In the course of his research about how people behave in social networks, Nicholas Christokis ran an experiment using data he gathered about shipwrecks that took place over the span of four hundred years. He wanted to know how survivors who had “narrowly escaped death and were psychologically traumatized,” often arriving on remote islands “nearly drowned and sometimes naked and wounded” came together (or broke down) as a network of survivors. His findings tended to prove his theory that we carry “innate proclivities to make good societies” even under the most extreme circumstances.

His “Lessons from Shipwrecked Micro-Societies” appeared in the on-line platform Quillette a little over a week ago. Christakis acknowledged many of his experiment’s limitations up front:

The people who traveled on ships were not randomly drawn from the human population; they were often serving in the navy or the marines or were enslaved persons, convicts or traders. Shipboard life involved exacting status divisions and command structures to which these people were accustomed. Survivor groups were therefore made up of people who not only frequently came from a single distinctive cultural background (Dutch, Portuguese, English and so on), but who were also part of the various subcultures associated with long ocean voyages during the epoch of exploration. These shipwreck societies were [also]…mostly male.

Still, given the similarities and differences among these survivor groups in terms of race, gender and hierarchy, it is noteworthy that they rarely devolved into a state of selfishness, brutality or violence in their quest to survive. Instead, they tended to model fairness and cooperation in their interactions, a reduction in previous status divisions, noteworthy demonstrations of leadership and the development of new friendships.

Survivor communities manifested cooperation in diverse ways: sharing food equitably; taking care of injured or sick colleagues; working together to dig wells, bury the dead, co-ordinate a defense, or maintain signal fires; or jointly planning to build a boat or secure rescue. In addition to historical documentation of such egalitarian behaviors, archaeological evidence includes the non-separation of subgroups (for example, officers and enlisted men or passengers and servants) into different dwellings, and the presence of collectively built wells or stone signal-fire platforms. Other indirect evidence is found in the accounts of survivors, such as reports of the crew being persuaded, because of good leadership, to engage in dangerous salvage operations. And we have many hints of friendship and camaraderie in these circumstances.

Christakis is best known for demonstrating how networks of strangers can promote positive behaviors and even altruism through “the contagion” that their influence exerts in the course of their interactions. His new book Blueprint: the Evolutionary Origins of a Good Society makes the additional argument that our genes affect not only our personal behaviors but also provide the drive to join together “to make good societies” whether they are in on-line networks or in the communities where we live and work. The encouraging data from shipwreck communities that Christakis summarized in his article is part of that argument.

In what can seem like a mean-spirited and selfish time, there is hope to be found in the circumstantial evidence that “helping one another” may be hardwired into our genetic programming.

There is hope to be found every time that regular people pitch in to help instead of walking by or refusing to get involved, not because they’re heroic or brave but because they experience something akin to enjoyment and even liberation by doing so.

Whenever hope in the future seems to be flagging, look for the helpers. There are several reasons that they’re always around.

This post was adapted from my July 21, 2019 newsletter. When you subscribe, a new newsletter/post will be delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning.

Thinking more broadly about what we value and bringing that perspective into new kinds of problem-solving in the commons seems the most fruitful way forward—however cobbled together my current game plan. If you’ve been thinking about what divides us today and what can be done to bring us together, I’d love to hear from you.

Thinking more broadly about what we value and bringing that perspective into new kinds of problem-solving in the commons seems the most fruitful way forward—however cobbled together my current game plan. If you’ve been thinking about what divides us today and what can be done to bring us together, I’d love to hear from you.