To make the hard decisions around climate change, we need the pull of a compelling story that tells us about all the great things that will follow and the ways we’ll be rewarded when we do.

Because changing the ways we live and work will be hard, disruptive, (and given the nature of change generally) uncomfortable, we’ll need to want, really want, what comes after if we’re ever going to bite all the bullets that we should be biting already.

So far, there’s not been enough biting—and the clock is ticking, at two seconds to midnight or whatever, like a cattle prod—because our imaginations have yet to be captured by a version of the future that gives us enough to look forward to so that all those necessary changes, “our adopting simpler lives fueled by windmills etc.,” will finally feel like they’ve been “worth it” when everything settles down again.

Or to illustrate with a different, supposedly dumb animal, if we’re ever to get through the maze of our fossil-fueled obstacles and over the desire to consume our entire planet, we’ll need a really strong whiff of the new cheese in the middle—and our twitching noses just haven’t picked it up yet.

That “we” is you and me of course, a really specific and fairly small number of Earth’s nearly 8 billion inhabitants. That’s because (as Rebecca Solnit wrote about so well this week):

By saying ‘we are all responsible’ [for the environmental catastrophe], we avoid the fact that the global majority of us don’t need to change much, but a minority needs to change a lot. This is also a reminder that the idea that we need to renounce our luxuries and live more simply doesn’t really apply to the majority of human beings outside what we could perhaps call the overdeveloped world. What is true of Beverly Hills is [simply] not true of the majority from Bangladesh to Bolivia.

So the people who need to be convinced by a better story are the relatively few of us who either live in this “overdeveloped world” or in gated communities with gun turrets in the less-developed parts of it.

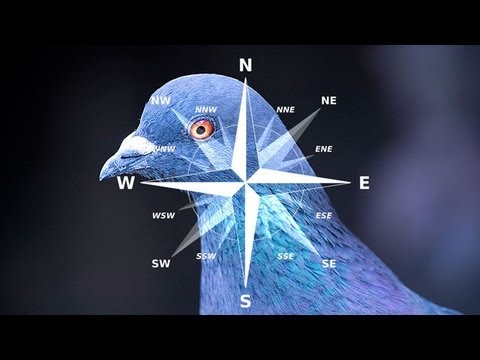

We are the ones facing the hardest, most disruptive choices. But, says Solnit, the only stories about what comes next and how we’ll get there are coming from scientists, with their mind-boggling charts and “climate models” and speculative technologies. Her call is for artists—on the scale of Dickens—or science fiction writers who can tantalize us with the promise of marvelous tomorrows instead of paralyzing us into “deer in the headlights” with their views of dystopian ones. (We really are like cattle, rats and deer.) Solnit also goes on to describe some of what these new storytellers should be weaving into their narratives and how they should go about doing so, but before we turn to her remarks a few words about the images—they’re photo collages—in my post today.

Because he includes “us” as passive spectators in our own disaster narratives, a 30-something visual artist who’s working in Brussels captures “where many of us are these days” quite affectively: tourists viewing their own apocalypse, swimming while the surrounding hills burn, jumping into the unknown when we could be helped to know (and even look forward to) whatever’s down there.

The artist’s name is David Delruelle, and by capturing today’s mood with his brilliant juxtapositions it’s almost like he wants to jar us out of our dumb-animal complacency. If you’re as captivated as I am by his work, here’s a link to a catalog that features more of it and another to a 4-minute video about the creation of these surreal visuals.

“La Boîte Verte (The Green Box)” or swimming while the rest burns.

The Solnit essay in The Guardian this week says it was adapted from a speech she gave at Princeton last November but in all the ways that matter it’s the most recent child of her 2004 book, Hope in the Dark. That book’s important arguments showed how history is written by committed individuals who find the conviction to take the next small step, in difficult times, towards a goal that seems beyond reach and may never materialize. That’s why the brand of “Hope” that Solnit writes about there needs to find its conviction to act “in the Dark” instead of waiting for the imminent victory of a rising sun.

Her Guardian essay describes the folly of expecting the battle against climate change (or whatever we’re up against) to unfold like a Hollywood action movie, yet that is what many of us seem to be magically thinking. (We won’t have to make difficult decisions. All we’ll need to do is wait for somebody else to sort things out and turn the lights back on.)

These movies also encourage the myth that our salvation will come in battles, fought by loners, with “the capacity to inflict and endure extreme violence,” while the skills that we’ll ACTUALLY need (according to Solnit) are “solidarity, strategy, patience, persistence, vision and the ability to inspire hope in others.” At the same time, the rescuers that will save us “are mostly not individuals [at all], they are collectives—movements, coalitions, campaigns, civil society [and]….We are sadly lacking in stories in which collective actions or the patient determination of organizers is what changes the world.”

A similarly fanciful lesson “from our [‘entirely inadequate,’ she’d say] films and fictions” is that there will be “a sudden victory, a celebration, and the trouble [will be] over.” From her own activism and from writing about social change for decades, Solnit has learned that “[c]hange often functions [more] like a relay race, with new protagonists picking up where the last left off,” citing the following example for resonance:

In 2019, a Berkeley city councilwoman decided to propose banning fossil-gas connections in new construction, and it was passed by the council unanimously. This small city’s commitment to all-electric new buildings could seem insignificant, but more than 50 other California municipalities picked it up, as did the city of New York. The state of New York failed to pass a similar measure, but Washington state succeeded, and the idea that new construction should not include gas has spread internationally.

The trick, as she describes it in Hope in the Dark, is to maintain your convictions and your hopes for the desired outcome at each stage of our real-world rely race, because without reserves of endurance during periods of uncertainty (and lots of new blood joining the chain), we often abandon our victories and concede our defeats too quickly. In that book, Solnit illustrates the quandary as well as our way out of it through this example, about the struggle for pay equity for women:

[A] cranky guy wrote in that women used to make sixty-two cents to the male dollar and now we made seventy-seven cents, so what were we complaining about? It doesn’t seem like it should be so complicated to acknowledge that seventy-seven cents is better than sixty-six cents and [at the same time] that seventy-seven cents isn’t good enough, but the politics we have is so pathetically bipolar that we only tell this story two ways: either seventy-seven cents is a victory, and victories are points where you shut up and stop fighting; or seventy-seven cents is ugly, so activism accomplishes nothing and what’s the pint of fighting? Both versions are defeatist because they are static. What’s missing from these two ways of telling is an ability to recognize a situation in which you are traveling and have not arrived, in which you have cause both to celebrate and to fight, in which the world is always being made and is never finished.

In her Guardian essay, Solnit introduces a dozen additional themes for inclusion in a story about the future that might motivate us to intensify our struggle against climate change in the ways that we need to—including these:

– how ending “an era of profligate consumption by the few that has consequences for the many means changing how we think about [and imagine] pretty much everything: wealth, power, joy, time, space, nature, value, what constitutes a good life, what matters, how change itself happens.” It’s both the challenge and promise of radical reinvention.

– how “we’ve largely won the battle to make people [who are like us] aware and concerned” already, but that the story also needs to mobilize us to take the necessary actions now (like cutting back on our consumption and valuing nature differently) for the sake of a future that can pull us towards it while never being a certainty.

– how improving our literacy about profound and fundamental change in the past (like the transformative nature of the Industrial Revolution, or even more recently, the rise of the smart phone) can fuel the effort to produce equally profound and fundamental changes for the sake of our future.

Each of these elements is part of a new story that will need to take us beyond the crisis of climate change to a world that we want to live in far more than the one we’re living in today. That story also needs to show us how to “break things we’re attached to” in order to get there, while dazzling us with the promise of its wonders and fullness once we arrive. Because as Solnit says so well in this, the heart of her remarks:

Every crisis is in part a storytelling crisis. This is as true of climate chaos as anything else. We are hemmed in by stories that prevent us from seeing, or believing in, or acting on the possibilities for change. Some are habits of mind, some are industry propaganda. Sometimes, the situation has changed but the stories haven’t, and people follow the old versions, like outdated maps, into dead ends.

We need to leave the age of fossil fuel behind, swiftly and decisively. But what drives our machines won’t change until we change what drives our ideas. The visionary organizer Adrienne Maree Brown wrote not long ago that there is an element of science fiction in climate action: ‘We are shaping the future we long for and have not yet experienced. I believe that we are in an imagination battle’….

[And since we are,] for too long the climate fight has been limited to scientists and policy experts. While we need their skills, we also need so much more. When I survey the field, it’s clear that what we desperately need is more artists.

What the climate crisis is, what we can do about it, and what kind of a world we can have is all about what stories we tell and whose stories are [engaging enough to be] heard.

“Great Mountain Fire” or jumping into the unknown.

In reviewing old posts that I’ve written about the challenges facing the health of the Earth—including the hazards of climate change, global warming and biodiversity loss—I was surprised by how hard I’ve been looking for that new story (or at least some key themes) that will mobilize me to reduce my consumption, find new forms of gratification (beyond eating the planet), stop the environmental damage I’m causing, restore what I can mend (like how to bring rabbits, or certain kinds of birds back to my backyard), discover new ways of living and working, and help to build a future that’s more satisfying than the one I’m anticipating today. So in closing, I’d like to add a few of the storylines and themes that I’ve considered to the ones that Rebecca Solnit is proposing.

– how something called “the Clock of the Long Now,” which calculates time 10,000 years into the future, operates as a kind of “act of faith” in our long-term prospects, and how we reaffirm that belief and the value of such a clock whenever we invite a new baby to join us down here. (Bringing a Child Into a World Like This, April 24, 2023).

– how we’re finding new ways to cover the costs to industries and workers of changing today’s harmful environmental practices. Demonstrating a kind of “virtuous economic circle,” this is a storyline about New England’s lobster industry, a declining right whale population, and how valuing the whales’ contributions to ocean health differently could finance changes in lobster trapping so current methods no longer endanger these migrating giants. (Valuing Nature in Ways the World Can Understand, November 13, 2019).

– how the UK’s government has gotten behind a breathtaking proposal to value nature like an asset, and natural systems like portfolios of assets, so a dollars & cents world can finally join in finding sustainable solutions to biodiversity with “a common grammar” of economic costs and benefits. (Economics Takes a Leading Role in the Biodiversity Story, February 21, 2021).

– and how the future can look better—more interesting and far more promising—when we put ourselves in that future and look back at how far we’ve come, because we’re finally experiencing the combined impact of the much smaller changes we made in the 2020s in areas like battery technology, urban design and soil management. (A Different Future Will Get Us Out From Under the Cloud, September 19, 2021).

Particularly as our political landscape degraded and the pandemic surged—that is, when the future seemed particularly bleak over the past few years—I dove into these stories to see if I could find in them “some hope in the dark” for me and maybe for you. And there was a kind of glimmer in the growing realization that our imaginations in the face of environmental peril might indeed see us through these daunting challenges.

Now if only I were enough of an artist to write the compelling story that could help to carry humanity to a more sustainable finish line. Or that someone far more talented could.

This post was adapted from my January 29, 2023 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes I post the content from one of them here. You can subscribe (and not miss any) by leaving your email address in the column to the right.