Jury Duty is a Slice of Life That You Want to Have

My reflex on getting called to jury duty is still “how can I get out of it,” but I know that’s mostly the reptilian, fight-or-flight part of my brain. Who’s asking, and why are you picking on me? But these days one of my higher order functions is quicker to declare (just a little more loudly): I hope that I’ll be fit enough to serve.

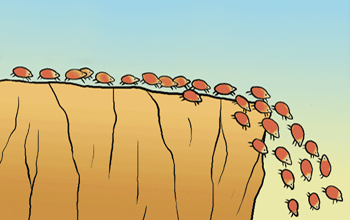

When put on notice for jury duty, nobody wants their routine to be interrupted, to rub elbows with strangers, or spend days in an airless courtroom for the bus fare plus change you’ll be paid. The first impulse is running the other way. But on the flip side of “No-o-o-o” are some pretty persuasive “yeses.”

Jury duty is a call for neighbors to come together and decide whether someone else who lives or works here has failed to act in the ways they’re supposed to. The first question worth asking is whether you want to have a say in the matter or leave it to someone else? In the 2016 presidential election, 40% (or more than 92 million eligible voters) left it for somebody else to decide—perhaps the most alarming statistic in America today.

“Being a good citizen” used to be all most people needed. You didn’t ignore the jury summons, the IRS letter, or a chance to vote for your representatives. Well no longer.

More of us are scofflaws today—literally scoffing at the law—because (maybe, hopefully) these civic obligations will just forget about us altogether if we keep on disregarding them. Here in Philadelphia, so many ignore their calls to jury duty (175,000 out of 545,000 summons issued in 2015) that the court system has simply thrown up its hands when it comes to enforcement. Of those who respond, my guess is that many do so grudgingly. This is A VERY BIG (AND RESENTFUL) VOICE that says: “I just don’t care enough to help decide ‘what’s acceptable’ and ‘what’s not’ for those of us who live here.”

I’d argue that jury duty is at least as “citizen-gratifying” as marching with a protest sign, but there are other benefits that may sound less like a civics course for those who still need convincing.

I was picked for a jury this week, so these benefits are fresh in my mind. Lawyers never used to get picked, but this was the third time for me. Aside from seeing one of the jobs I do from an entirely different angle, the two most compelling pluses involve connection and storytelling. Here’s what I mean.

The deeper we dive into our phones, the more disconnected we become from other people. There is nothing like a closet-sized jury room to introduce you to members of your community. In your hours together, you share snippets about lives and work, while your deliberations together are an intimate opportunity to encounter them through their senses of right and wrong. Close quarters seldom get warmer than that.

Particularly in big cities, the other jurors are likely to come from different “walks of life” than your neighbors next door. The bubbles we increasingly inhabit have everyone looking more or less the same and agreeing about nearly everything. A Philadelphia jury allows very different bubbles to touch and merge for a brief common purpose, and that’s been a cause for optimism each time I’ve experienced it. When you fear that America’s sky is falling, you are reminded how FUNNY, WISE, HUMBLE and DECENT other members of the public can be when you come together this way.

The stories you see and hear as a juror also tend to make the ones you’d otherwise be following pale in comparison. Sometimes the vivid characters or plot lines emerge from friendships that develop among jurors. As often, they’re from the comedies and tragedies that are playing out in front of you in the courtroom.

The comedy is usually unintended. This week, for example, counsel for a widow suing her husband’s doctors had such a strong accent that when he introduced himself all he could communicate to us clearly was his first name. His elderly client entered the courtroom in a wheelchair that appeared to be stolen from one of the airlines. And the attorney for the doctors had a skirt that was so short she practically mooned us when she sat down after introducing herself. There are no second chances to make first impressions like that.

But the stakes involved in “who’s telling the better story” can also be soul crushing or inspiring. I’ve also been on a jury that had to decide whether to impose the death penalty. Before we were selected, the testimony from the potential juror pool on their beliefs about crime and punishment said more about personal character than you’re likely to hear anywhere else.

The defendant in this case had allegedly killed his confederate in a drug deal, along with several potential witnesses who were unlucky enough to be there too when it all went down. The prosecutors thought they were hotshots. The accused was a 20-something who seemed impossibly blasé about being there. Whose facts would we believe—whose story—with this many lives in the balance?

Every trial is not a murder trial, but it’s also true that the rest of our lives rarely approach the influential place where jurors go to work everyday. As a juror, you’re helping to decide how one storyline in your community draws to its conclusion. For a little of your time, you become a character in the narrative, part of its truth as well as its consequences.

A version of this essay appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer on March 12, 2017. It also appeared in Newsday, the Charlotte Observer and Cleveland Plain Dealer.