“If those around him had known how to intervene to stop him, it would never have gotten to this point,” someone might have said about New York Governor Andrew Cuomo recently.

I wasn’t expecting to write about bystander interventions today, but was jarred (as many were) by the longstanding accommodation of Cuomo’s harassment. His temper, directed at everyone in his orbit, was a common secret. Like Churchill once said about Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, Cuomo was apparently another “bull who brings his own china shop with him.” But in addition to the tolerance that those around him had for his temper tantrums, Cuomo’s groping and touching were also common knowledge. Many around him knew he was grabby with women, but none of them intervened to stop him (or protect him from himself), so apparently it became “the way that things were for years” if you were in the Governor of New York’s orbit.

The longstanding tolerance for Cuomo’s conduct reminds me of Harvey Weinstein’s decades-long run of predatory behavior in Hollywood. Like Cuomo, those in Weinstein’s sphere of influence were afraid of crossing him because they relied on the power of his support and feared the wrath that might jeopardize it. Too many came to feel that accepting Weinstein’s abuse was the price of admission. And because (like Cuomo) the power disparities between Weinstein and almost everyone else were so profound, “the way he acted” became an open secret, widely known and effectively normalized, while he continued to groom his prey and damage more lives.

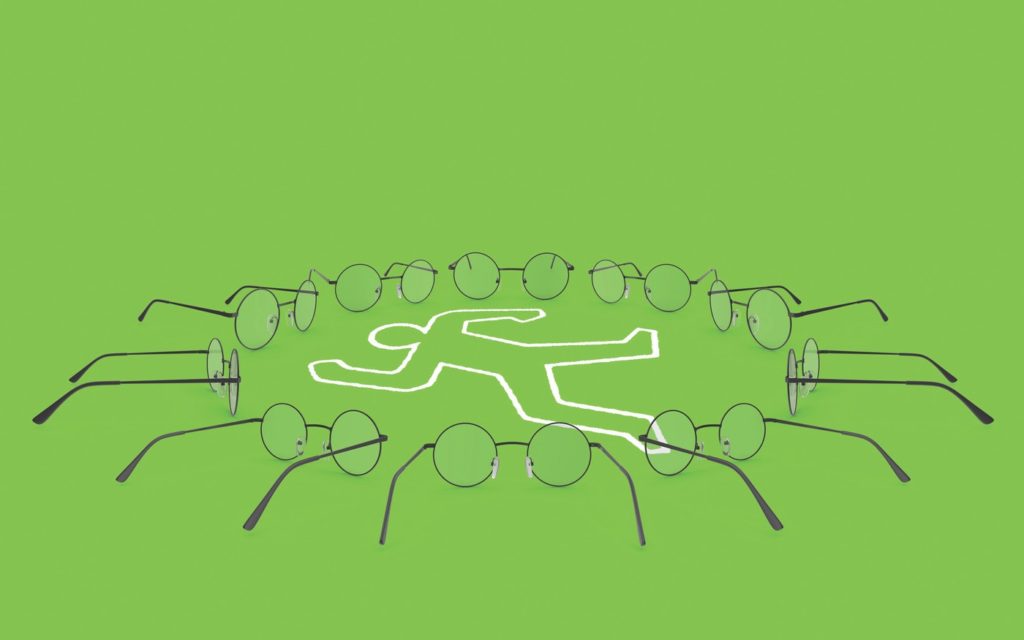

Because so many in the entertainment business “knew about Harvey,” those who were “in on the joke” regularly got to have an uncomfortable laugh when somebody (usually a comedian) had the gumption to drag the stinking truth onstage.

As reported by one outlet after his first accusers got press coverage, the finger pointing had been ongoing in mainstream comedy for years. For example, Weinstein’s behavior was a punchline in the TV show “30 Rock,” where the character played by Jane Krakowski says in one episode: “I turned down intercourse with Harvey Weinstein on no less than three occasions out of five.” And while announcing actress nominees for an Oscar in 2013, comedian and comedy writer Seth MacFarlane joked in front of Weinstein himself, the rest of those in the “live” audience, and the 40 million people viewing on TV: “Congratulations, you five ladies no longer have to pretend to be attracted to Harvey Weinstein.” As time goes on, we’ll probably hear about the jokes that staffers and favor-seekers in Albany were telling one another about Cuomo too, instead of doing anything more than laugh among themselves about it or cringing in a corner as he headed their way.

Part of what was so compelling here was the high visibility of Weinstein’s and Cuomo’s misconduct. After all, they were acting out their dark fantasies in Hollywood and the Empire State, with their wall-to-wall press coverage, enterprising scoop-hunters, and hangers-on with blackmailing agendas. Yet for both of them, it took years and a long trail of victims before collective action started to puncture their skeevy underbellies.

Clearly, some basic checks and balances were missing in the workshops that Weinstein and Cuomo once dominated.

Clearly, far too few at their stratified elevations knew how to inoculate their workplaces from the diseases that undermined them, along with every individual who worked with these two and tacitly permitted their misconduct.

Clearly, Weinstein/Cuomo/comedians Bill Cosby and Louis CK/artist Chuck Close/ former House Speaker Dennis Hastert/former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick/former Olympic gymnastics’ doctor Larry Nassar/all those victimizers in the American military who continue to act with impunity towards their subordinates: each of them was or is enabled by others in their reigns of terror, and it was more than their closest victims that lost something of value by not having healthier places to work before “what almost everybody seemed to know already” finally became unacceptable.

In the wake of the report about Governor Cuomo by New York’s attorney general in early August, there was a brief interview with an employment law professor named Marcia McCormick about redesigning employee training and reporting systems to fight sexual harassment in the workplace. What caught my attention was the interview’s focus on “activating bystanders” who already knew about the harassment so they could join in the fight against it.

This angle in the discussion could be traced back to a 2016 report by the EEOC (or Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) which insisted that victims were not the only ones who needed to know the rules about workplace harassment and discrimination; every employee needs to be empowered to challenge both perpetrators and their fellow employees to drive predatory conduct out of the workplace. Said Professor McCormick:

[B]ystander training in particular is very effective, to allow co-workers [of the person being harassed or discriminated against] to intervene in ways that are not [as] risky to them…[W]hen people complain about discrimination against themselves…they are perceived to be whiners. Their complaints are sometimes not taken seriously…[but] when a person advocates on behalf of another, that usually doesn’t happen…[R]eporting by a bystander doesn’t trigger the same kind of psychological backlash and potential for retaliation that the person who experiences it might.

Moreover, when all employees are trained to recognize, intervene and demonstrate their solidarity with targets of illegal behavior, they are better able to disrupt new overtures before they happen and help victims to report and gain more backing from fellow workers afterwards.

A 2018 article in Harvard Business Review acknowledges that empowering an entire workforce like this is a lengthy and difficult task (far more so than having “a canned training session” and an employer’s checking “the legal liability box” afterwards) but when executed properly, empowerment training almost immediately begins to deter likely perpetrators, from the boss’s office on down. This is how one expert described the root problem that needs confronting to the article’s author:

Jane Stapleton, co-director of the Prevention Innovations Research Center at the University of New Hampshire and an expert in bystander interventions, told me about an all-too-familiar scenario: Say there’s a lecherous guy in the office — someone who makes off-color jokes, watches porn at his cubicle, or hits on younger workers. Everyone knows who he is. But no one says anything. Co-workers may laugh uncomfortably at his jokes, or ignore them. Maybe they’ll warn a new employee to stay away from him. Maybe not. ‘Everybody’s watching, and nobody’s doing anything about it. So the message the perpetrator gets is, My behavior is normal and natural,’ Stapleton said. ‘No one’s telling him, I don’t think you should do that.’ Instead, they’re telling the new intern, ‘Don’t go into the copy room with him.’ It’s all about risk aversion — which we know through decades of research on rape prevention, does not stop perpetrators from perpetrating.

Once again, when the bystanders aren’t empowered to act, harassing and discriminatory behavior is “normalized” in the same way that rape or child abuse is normalized when the family where it’s happening pretends that it’s not.

Enabling bystanders, the author writes, “is leveraging the people in the environment to set the tone for what’s acceptable and what’s not acceptable behavior.”

A still from the 1985 movie, Witness

Because I’m sometimes unable to act on my best (or even better) impulses when confronted with something that seems wrong, I spent a lot of ink in early book drafts considering how any of us might do a better job of it.

From behavioral studies that delved into the mechanics of helpful intervention, it seems that the cure for bystander inertia comes in two doses: already having a better plan in mind before the unacceptable happens and seizing the occasions to act on your plan when it does.

The deeper I dug, the more I appreciated how visualizing the path we want to take before being called up to act almost always improves our responses. It’s the difference between being ready when the time comes versus having to make up what you’ll do (or far more commonly, refrain from doing) on the spot. But this requires preparation. You have to want to act in a certain way—like treating others in the same compassionate way that you hope they’d treat you in similar circumstances—so you’ll make the effort to devise a plan that you’ll already have it in your pocket when the need arises.

If it’s really as simple as that, why weren’t more people in Weinstein’s or Cuomo’s or other predatory orbits—and why aren’t more onlookers of “bad stuff” generally—able to follow their better angels and intervene to stop (or at least help in stopping) the damage that they’re witnessing?

In my case, I’ve usually been delusional enough to imagine that “I’ll be as brave as my best hopes” when I’m called upon by circumstance to right some wrong, or stand up for somebody who needs my help. Unfortunately, whenever I’m surprised by the need to intervene in a bad situation, I usually find it easier to fret about my skill set, whether I want to get involved or have enough time, or if someone else is in a better position than I am to step in and make a difference. In other words, my hoped-for better self usually never shows up and I end up making lame excuses to explain to whomever’s listening why I failed to do much of anything at all.

In research I did at the time, I learned that it doesn’t have to be this way, that even considering my thoughts and feelings more deeply in advance of witnessing, say, sexual harassment at work or one stranger being tormented by another, would likely have enabled far better responses on my part.

One study I found had some of the study participants attend a lecture on the ethics around rescue and the bystander effect (where they’d presumably imagined their own responses to various situations) and other study participants who missed that lecture, before all of them encountered a stranger who’d actually fallen and couldn’t get up outside the lecture hall. While the scenario was staged by the study’s authors, its findings were not: 43% of those who’d just attended the lecture ended up coming to the victim’s aid, while only 25% of bystanders in the study who’d missed the lecture stopped to offer their help. It’s a resonant statistical difference between those who already knew something about overcoming bystander reluctance and those who never may have thought about it at all. (Notwithstanding these findings, I still recall being surprised and disappointed by the fact that only 43% of the lecture goers actually stopped to apply what they’d just supposedly learned!)

Another study revealed that even taking a relatively minor step “in the right direction” (beyond just learning more about it and imaging how you might act beforehand) makes an additional difference in determining how you’ll act or fail to act going forward. This tendency was demonstrated by an experiment in which some teenagers pledged to remain virgins until marriage while others in the study were never given the option to make such a pledge. Given teenage hormones, It doesn’t seem like much of a commitment, but this study found that those who took the pledge had sex much less often than the non-pledgers. Indeed, even the non-pledgers who said in advance that they supported abstinence before marriage ended up having sex far more frequently than their pledge-taking peers. In other words, even as small an act as making a verbal commitment tended to reinforce attitudes and lead to behavior that was consistent with one’s helpful intentions going forward.

To test this behavioral guidance system—and to pay-it-forward on behalf of all who had came to my assistance over the years when my car has broken down on a busy road—I did some of my own committing in advance. The next time I saw a car broken down in traffic, its driver in distress and I could pull over safely to help, I promised do so. I rehearsed the likely scene in my mind, and a couple of months later the opportunity presented itself.

A woman outside of her car was being confronted by an angry truck driver during rush hour on North Broad Street in Philadelphia after an apparent collision. I could and did pull over and offered her my assistance which, after some initial surprise (who is this white guy in a suit offering to help me?), she ended up being visibly grateful for.

Without an action plan, I would likely have found a dozen excuses for not stopping. Once I acted, I knew even better what I’d do the next time, the likely range of emotions I’d feel while intervening, and the best part, how I’d feel afterwards—which was genuinely enabled. On the other hand, without a plan of action beforehand, my hopes alone about being a helper would likely have left me at the bystanding sidelines.

When we want to, it’s not so hard to empower ourselves towards helpful action.

It’s not so hard to train ourselves to help confront the Weinsteins and Cuomos who can end up dominating our worklives by finding ways to move in a constructive way beyond the “common secrets” and “inside jokes” about the boss or “that guy over there” or the touchy-feely holiday party.

It’s learning about the bystander inertia that naturally holds us back by plotting our ways to helping when the need arises.

Maybe when more of us make this commitment, there will be enough people in every workplace who are ready, willing and able to intervene on behalf of victims who will almost never be vindicated when standing alone.

This post was adapted from my August 8, 2021 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning and occasionally I post the content from one of them here. You can subscribe by leaving your email address in the column to the right.