Someone starts telling a story so that those who are listening can start imagining.

We need stories that challenge us with new ways to find political consensus, to confront climate change, to learn from the triumphs as well as the shortcomings of our common past.

Without the liberation of stories like that, we can be paralyzed when confronting the hostility of our politics, the inevitability of a rapidly degrading earth, and the unfinished work of our imperfect but often noble forebears.

And sometimes, as with this particular story, no less than Prince Charles, Boris Johnson and David Attenborough were invited to play bit parts on the story’s opening night (more about that below).

These very different men stood front and center for a few minutes because this story had already invited them into it. When a storyline is bold and surprising, curiosity often finds famous listeners before it blossoms into broader engagement and we’re sharing it with those that we care about too.

A report presented earlier this month begins to tell such a story, skillfully deploying economic theory to get our juices flowing in new directions.

– It admits what we already know: that humanity is taking more from the earth—extracting more of its minerals, fishing more from its seas, destroying more of its diversity, undermining more of its climate patterns, polluting more of its habitats—than the earth can replenish, correct or restore on its own.

– It wonders out loud—in a flight of real-world imagination—about what might happen if we treated Nature’s systems and productive capacity not as “free” for the taking (as we still do almost everywhere today) but as “economic assets” that we must start “investing in” (like we invest in the homes where we live) and managing, as we would any “portfolio.” We’d utilize concepts like “asset value” that acknowledge not only the price that a natural asset commands in the marketplace (its so-called “use value”), but also its “intrinsic value” as part of an ecosystem “that is greater than the sum of its productivities” and contributions. Similarly, we’d account for the “depreciation” of these assets so we could understand their diminishing value to us and their systems as we continue to rely upon them.

– It’s a story that begins to tie “the regeneration of the biosphere…to the sustainability of the human enterprise” (or our economic activities on this planet) in a way that’s never been told before.

– It’s a story whose drama comes from the uncertainty of our survival because, given the current rate of Nature’s depletion and imbalance, the Earth will be unable to sustain life as we know it into the foreseeable future.

This story, formally presented earlier this month by the U.K.’s Treasury Department, was written by Cambridge University professor Partha Dasgupta and is called The Dasgupta Review on the Economics of Biodiversity. You can read an abridged version of it (around 80 pages) or his full Review (at 600 pages) by downloading them here.

The Dasgupta Review begins with the simple observation that: “We are all asset managers.” Professor Dasgupta then describes how we all must learn to manage Nature’s limited and deeply-troubled portfolio of assets in ways that an economist might:

Nature’s goods and services are the foundations of our economies. They include the provisioning services that supply the goods we harvest and extract (food, water, fibres, timber, medicines) and cultural services, such as the gardens, parks and coastlines we visit for pleasure, even emotional sustenance and recuperation. But Nature’s processes also maintain a genetic library, preserve and regenerate soil, control floods, filter pollutants, assimilate waste, pollinate crops, maintain the hydrological cycle, regulate climate, and fulfil many other functions besides. Without those regulating and maintenance services, life as we know it would not be possible.

Biodiversity is a characteristic of ecosystems. It enables ecosystems to flourish and supply [this] wide variety of services… [J]ust as diversity within a portfolio of financial assets reduces risk and uncertainty, so biodiversity increases Nature’s resilience to shocks, and thereby reduces risks to the ecosystem services on which we rely.

As breathtaking a view of “a new world” as Tolkein’s (in fantasy) or Asimov’s (in science fiction), Dasgupta’s storytelling perspective invites us to imagine how governments, businesses, and individuals whose work depends on the vibrancy of Nature’s goods and services, along with the rest of us who enjoy the quality of our lives on this planet, can begin (at last) to sustain “the economic value” of the Earth’s biodiversity for everyone’s benefit. As surprising as it might seem, there has never been anything quite like The Review before.

Well into the 1970’s, we almost universally believed that human ingenuity could free us from Nature’s constraints and limitations. They were the days of “the Green Revolution” which brought rapidly increasing crop yields to smaller and smaller plots of land. They were the days when concerns about “over-population” (such as those voiced by Paul Ehrlich—a contributor to The Review) seemed grotesquely exaggerated. Until quite recently, we’ve acted like the Earth’s ability to fuel our continued “economic growth” and improve our living standards would be inexhaustible as long as human genius helped it along. Today, as we approach the environmental brink, we’re not only confronting our hubris but also beginning to storyboard our way out of the dead-end street where we currently find ourselves.

Even the abridged version of The Review will familiarize you with Dasgupta’s artistry when he identifies Nature’s asset classes and how they impact one another, how the planet’s stakeholders need to “re-invest” some of their profits into portfolio replenishment, and how all of us need to learn more about Nature’s “webs of interrelatedness” so that we’ll be more personally invested in managing these assets in our backyards and beyond them.

The Review is too rich in detail to summarize here and I hope you’ll to read it. But if you need more encouragement, an hour-long video-introduction to its findings, an overview teed up by the forenamed personalities, might convince you.

Why limit your exposure to Britian’s royals by watching another episode of The Crown? For example, I couldn’t remember the last time that I’d heard the real Prince Charles talk about anything important, but he puts himself garumphingly behind the findings of The Review in this film clip. Then, in a startling juxtaposition, there’s a wild-haired Boris Johnson putting his government behind proposals that have easily-imagined economic consequences for his voters (much like an American president announcing “exciting new taxes”), but here he is doing precisely that. And if you need even more convincing, the beloved naturalist David Attenborough writes the introduction to The Review itself.

As a storytelling exercise, here are perhaps the keys to how we can start imagining and then protecting the Earth’s biodiversity. In his video remarks, Professor Dasgupta says the Review’s contributions include:

[a new] grammar for understanding our engagements with Nature, how we transform what we take from and return to it, why and how in recent decades we have disrupted Nature’s processes to the detriment of our own and of our descendant’s future, and what we can do to change that direction.

What then is to be done to direct humanity to a sustainable mode of living, to reducing the gap between what we demand of Nature and what Nature is able to supply on a sustainable basis? It requires that we reduce our demand and help to increase Nature’s supply. It will require measured but transformative change for the task is to so change individual incentives that they direct the choice of our actions to actions that align with the common good.

This will require an implementation effort that easily dwarfs the Marshall Plan after World War II. Sometimes, the scale of The Review’s efforts to marry economic with environmental dynamics can take your breath away.

While economic incentives will be utilized locally to sustain the planet, an international equivalent of the WTO or World Bank will also need to be created to address (say) far-flung extraction practices in the Arctic and Antarctic, in the seas beyond territorial boundaries, and in places like the Earth’s rainforests, all of whose economic benefits are continental if not global in nature. As a piece in the New York Times observed when The Review came out:

International arrangements are needed to manage certain environments that the whole planet relies on, the report says. It asks leaders to explore a system of payments to nations for conserving critical ecosystems like tropical rain forests, which store carbon, regulate climate and nurture biodiversity. Fees could [also] be collected for the use of ecosystems outside of national boundaries, such as for fishing the high seas, and international cooperation could prohibit fishing [and other kinds of resource extraction] in ecologically sensitive areas.

New governance bodies that will monitor and value global assets while also collecting and re-distributing asset-related payments and fees in a kind of global clearing house are difficult–but still necessary–to start imaging, particularly at a time when competition among nations instead of international cooperation is on the rise.

The Review’s recommendations are also built upon a staggering number of economic checks and balances that will need to be administered locally.

A little more than a year ago, because I was unable to wrap my mind around a global model of this complexity without a “grammar” like Professor Dasgupta’s, I tried to imagine how economic incentives might support biodiversity closer to home. I looked at current research on lobster trapping in the Northeastern U.S., how the harvest impacts migrating whales, and whether the lobstermen could be reimbursed for changing their harmful trapping practices by monetizing the whales’ broader ecological value. A 2019 post called Valuing Nature in Ways the World Can Understand was my attempt to comprehend the economics of sustainability in a situation that had a smaller number of stakeholders and far fewer asset variables.

By contrast, the story told inThe Review is both top-down and bottom-up, envisioning at its horizons a dizzying array of parts that will eventually move in a synchronized fashion, but Professor Dasgupta ends his narrative with the same dilemma that probably led me to my post about lobsters and whales. We will never protect the Earth’s biodiversity until we understand the value of protecting it much closer to where we live and work. As he astutely notes, that’s because no international or local enforcement system can protect the diversity of life on this planet. That’s our job.

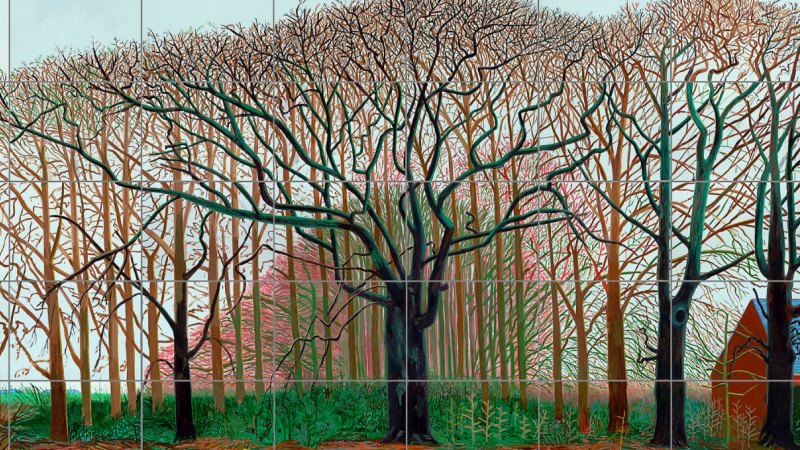

[U]ltimately, we each have to serve as judge and jury for our own actions. And that cannot happen unless we develop an affection for Nature and its processes. As that affection can flourish only if we each develop an appreciation of Nature’s workings, [my] monograph ends with a plea that our education systems should introduce Nature studies from the earliest stages of our lives, and revisit them in the years we spend in secondary and tertiary education. The conclusion we should draw from this is unmistakable: if we care about our common future and the common future of our descendants, we should all in part be[come] naturalists.

It’s a point that bears repeating. We will only treat the natural diversity that’s around us like an asset when we’ve gained “an affection” for it. Some of us gain that affection naturally but most of us—particularly in the developed world–have to learn it. A story like this one about imagination and survival invites us, both elegantly and engagingly, to do just that.

This post was adapted from my February 21, 2021 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning and occasionally I post the content from one of them here. You can subscribe too by leaving your email address in the column to the right.