In a much quoted phrase, Rebecca Solnit said that: “Sense of place is the sixth sense, an internal compass and map made by memory and spatial perception together.”

I tried to track down where Solnit said this, but (apparently) once something that you’ve said becomes “a famous quote” it tends to live in the ether alone, untethered to its origin. But it doesn’t really matter, because so much of Solnit’s writing over the past 30 years has been about what it means to fully inhabit a particular place—like the boat above, locating itself within the present, as well as by longitude and latitude, memory and destination, under the stars and above the depths of the sea.

Solnit is a kind of wandering minstrel and storyteller who rouses her readers into awareness (and even to action—like in Hope in the Dark), by drawing on her own deep engagement with the world. As an observer of turn-of-the-century life, she has written field guides that almost anyone who has read them seems to want to follow.

These field guides embody what Solnit means by Sense of Place: a lived experience that includes the present time, memories and dreams about particular pasts and futures, along with the stories of others who share the experience of those places with you.

Why does this almost cosmic sense of geo-location matter? Maybe it’s because we’re so unmoored today, with facts themselves in flux, mobs at war with one another, and 24/7 cycles of news and social media commentary that usually gravitate towards the “unsettling” while failing to put “what’s being blared about” into any kind of meaningful context.

As it becomes harder to find perspective or comfort–a useful frame for lived experience–it’s always possible for us to sink down deeper and more nurturing roots and to gaze into more promising horizons by the conscious act of locating our living and working within the rich variables of the particular places where they unfold.

Rebecca Solnit helped me to do this in a very specific way a couple of years ago. Among her many writings are a series of travel books about U.S. cities she’s been drawn to (like San Francisco and New York) and they include her insights about them along with telling points of view from others like local musicians, autobiographers, oral historians and weather experts. Each of these storylines is accompanied by detailed maps that follow each angle or interest from actual place to actual place in these cities. So before I returned to New Orleans two years ago, I took her Unfathomable City: a New Orleans Atlas (with all its maps and previews of coming attractions) with me.

Here she is, writing (with her co-author) about their intentions for this book in its opening essay:

We have mapped New Orleans and its surroundings twenty-two times, sometimes with two or more subjects [or areas of interest] per map, but we have not drained the well with these few bucketloads.

Instead we hope we have indicated how rich and various, how inexhaustible is this place, and any place, if you look at it directly and through books, conversations, maps, photographs, dreams and desires.

One of these extraordinary maps eventually brought me to New Orleans’ “cities of the dead” and, more particularly, to Holt Cemetery, which is the City’s potter’s field (or place where those who can’t afford a traditional burial, put their loved ones into the ground). I included a picture essay about my visit there in a 2019 post called A Living Rest. From her field guide, I discovered that local families have picnics at the gravesites, refreshing them with flowers, momentos and messages as they honor and continue to correspond with their family members for months and even years.

Solnit has not written a travel book about Philadelphia, but her curiosity led me to a potter’s field closer to home at a time when a disproportionate number of my neighbors were dying unvaccinated and a charitable corner of Chelten Hills Cemetery seemed to be exploding with activity every time I passed by.

In Same World Different Stories from a couple of months ago, I posted pictures from Chelten Hills potter’s field and talked about how that visit and what I took away from it deepened my appreciation of the place where I live, while at the same time it got me thinking about my own mortality and how it will be marked in the ground and on other peoples’ memories.

This picture shows how a Gingko’s fan-shaped leaves turn yellow just before, in a mad rush, they drop down all at once- like a loose pair of pants.

Another sense-of-place marker for me is the Gingko tree that nestles in the armpit of a majestic Tulip next to my house.

Before we get to his sense of the extraordinary place where he currently resides (below), novelist Richard Powers wrote memorably about trees in general, and about Gingko trees in particular, in The Overstory, a book that won him the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction two years ago:

Adam looks and sees just this: a tree he has walked past three times a week for seven years. It’s the lone species of the only genus in the sole family in the single order of the solitary class remaining in a now–abandoned division that once covered the earth—a living fossil three hundred million years old that disappeared from the continent back in the Neogene….

The fruit flesh has a smell that curdles thought; the pulp kills even drug-resistant bacteria. The fan-shaped leaves with their radiating veins are said to cure the sickness of forgetting. Adam doesn’t need the cure. He remembers. He remembers. Gingko. The maidenhair tree….

Its leaves leap out sideways in the wind…. It falls from one moment to the next, the most synchronized drop of leaves that nature ever engineered. A gust of air, some last fluttered objection, and all the veined fans let go at once, releasing a flock of golden telegrams down West Fourth Street.

In this single tree, Powers conjures familiarity (“he has walked past [it] three times a week for seven years”); its deep roots in time (“back to the Neogene”); its awful and magical properties (“a smell that curdles thought” while it’s “said to cure the sickness of forgetting”); its mythical moniker (“the maidenhair tree”) and perhaps its greatest trick (“the most synchronized drop of leaves that nature ever engineered”).

I now recall all of those things when I walk under the dual archway of Tulip and Gingko on the northwest edge of my house as it marks the season’s time every year in my own particular place.

It depends on when it’s cold enough, or cold enough for long enough, or when it gets subsurface signals from the Tulip that presides over everything that lives under its massive canopy that the time has come for your leaves to fall.

How will Philadelphia’s warming, its longer “Indian Summers,” effect the great drop when it finally happens in a month or so? I want to be ready, because in most previous years, I’ve tried to stand below its rain of yellow softness, as soft as this because none of its leaves have lost their cooling moisture yet and their skin still feels supple, a light kind of velvet. They’ll blanket me (and sometimes Wally) with everything below them in a shag rug of Asian fans. Nothing else feels quite like it.

The Gingko that lives here is a time piece, but not of the 24-hour variety. It has some deeper, environmental clock in the complicated network where it lives. This time of year, I keep some of my time by it too.

We’re hard-wired to navigate through space and time too.

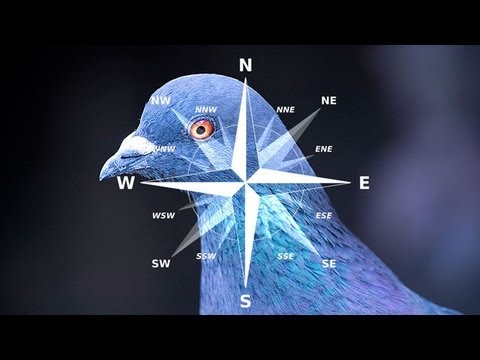

M.R. O’Connor’s Wayfinding: the Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the World (2019) looks to neuroscientists, anthropologists and master navigators to understand how our ability to navigate through space and time gives us an essential part of our humanity. But before climbing the evolutionary ladder to our human ancestors, she begins by discussing the extraordinary geo-location and time-keeping abilities of migrating birds and animals.

For example, humpback whales can travel thousands of miles before returning to the inlet or estuary where they were born. Bird species like flycatchers, blackcaps and buntings appear to adjust their flight patterns to the pole star when flying at night. Honeybees may visit hundreds of far-flung flowers during their miles of daily travel but still manage to find their way back to their hives by nightfall. Some dung beetles, desert spiders and cricket frogs have been found to use stars in the Milky Way like a compass. As O’Connor recounts, nearly every insect, bird and animal that’s been tested has demonstrated the ability to orient itself to the earth’s geomagnetic fields.

Humans have retained some of these capabilities to navigate through space and time while (sadly) allowing others to atrophy, because like all capabilities they require regular use and exercise. The “wayfaring” of O’Connor’s book title comes from American psychologist James Gibson, who used the word as a kind of informal shorthand for spatial navigation. “There [is] no separation between mind and environment, between perceiving and knowing,” Gibson wrote. “Wayfinding [is] a way that we directly perceive and involves the real-time coupling of perception and movement.”

To read O’Connor’s book is to find out about the remarkable navigational abilities of tribal peoples like the Inuit of Arctic Canada, the Australian Aborigines, and the native peoples of the Marshall Islands and Hawaii who learn to navigate thousands of miles of featureless ocean without maps or modern technologies. Their skills could be our skills if we made the effort to develop them.

We find our extraordinary sense of place through the integrative functions of our brain’s hippocampus, which enables us to “locate ourselves” through various points of view, prior experiences, memories of traumatic and nurturing events as well as by recognizing our goals and desires. Particularly while we’re asleep, the hippocampus helps to organize where we’ve been and hope to navigate tomorrow into a meaningful and sustaining narrative. Key to these inner workings may be the time-and-space orientations that we first developed as children, with early home life exerting a disproportionate influence on how comfortably we navigate the rest of our lives. O’Connor writes:

Often the places we grow up in have an outsized influence on us. They influence how we perceive and conceptualize the world, give us metaphors to live by, and shape the purpose that drives us — they are our source of subjectivity as well as a commonality by which we can relate to and identify with others.

These formative influences give us the perspectives that we use to test all new points-of-view. They show us (or never quite manage to teach us) how to navigate romance or office politics, how to encounter a stranger or weather a global pandemic. Towards the end of her book, O’Connor gets almost poetic while discussing the navigational aptitudes that we either nurtured at an early age or can learn to nurture today from deep within the temporal lobe of our evolutionary brains and out into the big, wide world around us.

Navigating becomes a way of knowing, familiarity, and fondness. It is how you can fall in love with a mountain or a forest. Wayfinding is how we accumulate treasure maps of exquisite memories.

Building our wayfinding capabilities can enable us to deepen our sense of place and to take more satisfaction from life as well as work by becoming more alive to the places where they’re located.

Mist, moss and branches that are busy returning to earth in an old growth forest.

While Richard Power’s The Overstory is about our external interactions with the natural world and our attempts to re-establish a restorative kinship with it, his new book, called Bewilderment,, is about the internal changes that need to occur in us if we’re ever to “come to our senses” and avoid an environmental catastrophe.

In this flipside of his earlier story, Powers uses his skills as a storyteller and student of science to show the impacts that the natural and social environments around us—that is, how the deep sense that each of us nurtures in the places we inhabit—can transform not only our personal well-being but also our collective ability to champion the health of the natural world for its own sake and for the sake of our interdependence with it.

To illustrate his ambition, Powers refers to a structural metaphor in a sweeping conversation he had with Ezra Klein 12 days ago in The New York Times. In the same way that “[we] shape our buildings and ever afterwards they shape us,” building our sense of place could change much that ails us today while preserving the restorative balances of our natural environments.

For example, Powers recounts how he moved, fairly recently, to one of the last places in North America unchanged by human “development,” a patch of old growth forest in the Smoky Mountains of Kentucky. He says of that journey:

[W]hen you stumble across an 1,100 or 1,200-year-old tree that’s as wide as a house and as tall as a football field, it puts a different context on your dinner table conversations with humans who are trying to [fend off aging and] escape death.

Untrammeled nature provides a time scale that’s beyond any individual’s concerns about living longer, having new conveniences or consuming one more Amazon delivery.

[W]hen I first went to the Smokies and hiked up into the old growth in the Southern Appalachians, it was like somebody threw a switch. There was some odd filter that had just been removed, and the world sounded different and smelled different. And I could see how elevated the species count was…. it’s really the first time in my life that I have lived where I live…

In his life before, Powers was always striving to be as productive as possible, “waking up every morning and getting 1,000 words that I was proud of.” But since moving East and publishing The Overstory,

my days have been entirely inverted. I wake up, I go to the window, and I look outside. Or I step out onto the deck — if I haven’t been sleeping on the deck, which I try to do as much as I can in the course of the year — and see what’s in the air, gauge the temperature and the humidity and the wind and see what season it is and ask myself, you know, what’s happening out there now at 1,700 feet or 4,000 feet or 5,000 feet.

You know, how much has it rained? How high are the rivers going to be? What’s in bloom? What’s fruiting? What animals are going to be at what elevation? And I just head out. I head out based on what the day has to offer….

I can’t really be out for more than two or three miles before my head just fills with associations and ideas and scenes and character sketches. And I usually have to rush back home to keep it all in my head long enough to get it down on paper.

For the first time in his life, Powers is sharing his sense of place with the natural world that’s around him. It’s not just a tonic for writers, it’s also a sensation that’s available wherever a sliver of nature is available to enter into a kind of kinship with everyday.

Of course for Powers, it’s not just the birds, animals, insects, trees and plants in this magical place, it’s also the people he can influence and collaborate with in his noble (or quixotic) quest for both inward and outward-facing transformation. In other words, what he’s selling is not only for those who will read and be changed by his books, it’s also to mobilize his fellow conservationists so that one day every one of us might be able to amplify the kinds of personal benefits that find Powers thriving in an old growth forest.

The largest single influence on any human being’s mode of thought is other human beings. So if you are surrounded by lots of terrified but wishful-thinking people who want to believe that somehow the cavalry is going to come at the last minute and that we don’t really have to look inwards and change our belief in where meaning comes from, that we will somehow be able to get over the finish line with all our stuff and that we’ll avert [an environmental] disaster, as we have other kinds of disasters in the past.

And that’s an almost impossible persuasion [or rose-colored mindset] to rouse yourself from if you don’t have allies. [But] I think the one hopeful thing about the present [moment] is the number of people trying to challenge that consensual understanding and break away into a new way of looking at human standing…. [I believe] there will be a threshold, as there have been for these other great social transformations that we’ve witnessed in the last couple of decades, where somehow it goes from an outsider position to absolutely mainstream and common sense.

In The Overstory and Bewilderment, we are invited to enter the “contraption” of two books that transform us while we read them. In different ways, each of them show us how enabling an external sense of place reinforces the same qualities that we use internally to organize time, space, memory and hope for the future. Powers’ genius is to argue that when the bond is strengthened like this, we’ll finally be able to start caring for the natural world as much as we’re caring for ourselves.

I’ve written about “sense of place” in other posts recently. Here are some links if you want to check them out for the first time or revisit them again: Technology Is Changing Us (how reliance on navigational technologies like GPS—that give us directions and destinations but no relational context—are causing us to lose, through disuse, capabilities that were once hardwired into being human); A Movie’s Gorgeous Take on Time, Place, Loss & Gain (The Dig is a story about using the history and experience of a particular place to bring what its inhabitants need most into the future that they most want); and Embodied Knowledge That’s Grounded in the Places Where We Live and Work (learning from people who are living and working on the edge of degraded environments so we also can start to embody some of the physical knowledge they have been gaining in order to survive in the years to come).

This post was adapted from my October 10, 2021 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes (but not always) I post the content from one of them here. You can subscribe and not miss any by leaving your email address in the column to the right.