For a semester or two in college I wanted to be a political cartoonist, but after drawing 3 or 4 for my college paper I gave it up as a career—although not gladly at the time. I was all over the place, and liked how confining my message to a panel or two simplified to the essentials what I had to say for myself.

A good cartoon is like fitting your point of view into Twitter’s original 140-characters. There is a discipline to visual or verbal restrictions like that, and I tend to drift out of the lines into smoke and blather without them. Unfortunately, political cartoonists are going the way of the printed newspaper and Twitter is letting us blubber on almost indefinitely these days.

That’s by way of saying that both of the stories below feature cartoons or cartoon-like images, because they make their points far better than I can.

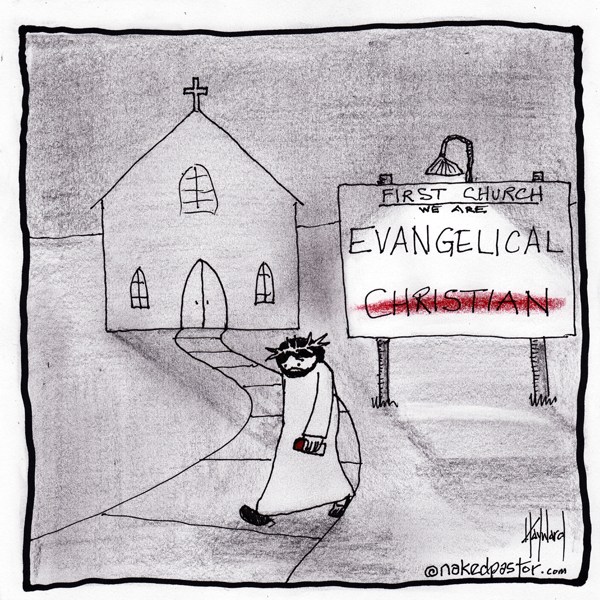

The first is about how organized religion no longer provides a space where most of us can meet regularly to figure out how to do good work and to live a good life. To the extent that houses of worship occupy our lives at all, most of them are no longer in the “values-forming” business. The second story is about Adrian Piper, an artist and philosopher who has found some of her own ways to fill this void.

I hope that you’ll reach out and tell me what you think.

Where Can You Go Today To Consider Doing Good Work or Living a Good Life?

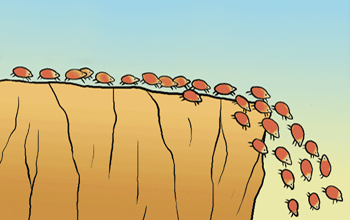

Many gatherings in the name of religion today are neutral containers that contain platitudes about love, respect or tolerance, tell stories about how much Jesus gave for us, or how hard Moses fought against our sinfulness. They rarely speak to what we’re going though in our lives or connect us to other people’s struggles and the wider world. They fail to give us a context for deciding what we should and shouldn’t do when we’re at home or at work–how we should act, the choices we should make. As a result, many of us who were raised in houses of worship have decided that it’s not worth returning to them.

On the other hand, those of us who continue to meet around a religious campfire do so less to develop our Judeo-Christian values and more commonly to confirm the political convictions that we’ve brought with us.

In her forthcoming book, “From Politics to the Pews: How Partisanship and the Political Environment Shape Religious Identity,” Penn professor Michele Margolis argues that:

Most Americans choose a political party before choosing whether to join a religious community or how often to attend religious services.

According to her statistics, since 1970 many who identify as Democrats have stopped going to church altogether while many Republicans have continued to attend religious services because doing so validates their political values. Smaller numbers of Democratic congregations have also begun to pursue their own progressive political objectives. Over the same 40 years, churches and synagogues that lack a political agenda have struggled to survive.

Before 1970, nearly all American houses of worship tended to have a politically diverse membership according to Margolis. As important social institutions, their religiously-sanctioned civility reduced political bias and fostered tolerance in their communities. This kind of civility is essential to productive, democratic exchange, and no other social institutions in America today are providing the moderating effect on our politics that houses of worship once did.

We need a place where we can meet to develop the values (like generosity of spirit) that are necessary if we’re to have an effective civic life.

Given escalating levels of political animosity, sociologists and political scientists have been looking into how the social exchanges between an individual and the groups that he or she belongs to affect that person’s politics. One study that Margolis cites has demonstrated that our meeting places (such as churches and schools) play a major role in determining how much partisanship influences our personal values. Another has confirmed what common sense had previously suggested, namely, that your exposure to conflicting political viewpoints enhances your respect for differing opinions; clarifies the bases for your own points of view; and improves your tolerance for and acceptance of those who disagree with you.

Without social institutions that can moderate our partisanship today, it’s difficult to imagine how Americans will learn how to cooperate again so we can start solving the important problems that affect us all. I’m thinking about providing affordable health care, fixing our crumbling infrastructure, and investing the monies that we need to support the oldest and educate the youngest in our society.

Rising hostility along our political divides and gridlock in government are our consequences as citizens of losing that shared space. But there are personal consequences too.

As our churches and our schools (America’s colleges and universities, in particular) have become places that confirm our partisanship instead of reducing bias and fostering a diversity of opinions, we are increasingly on our own when deciding what to do and not do with the rest of our lives and work. Many if not most of us have no place at all where we can ponder with others how to live a good life or do good work.

Perhaps in response, the ways that Adrian Piper has been living and working may help us fill at least some of this void.

Adrian Piper’s Valuable Witness

Artists can see into the future better than the rest of us. Given their own visions of a life worth living, philosophers use the rigor of their arguments to tell us how we should live and work to claim that future. Adrian Piper has been filling both of these roles since her work began in the 1970’s.

You may have caught some of the publicity around her current show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The museum is currently hosting the largest exhibit it has ever mounted of a living artist’s work (a 50-year retrospective of Piper’s contributions). Embracing her dual commitments, the New York Times reporter who covered the show said: “you see thinking happening right before your eyes.” It’s a dynamism that makes “the museum feel like a more life-engaged institution than the formally polished one we’re accustomed to.”

I haven’t seen it yet, but I hope to.

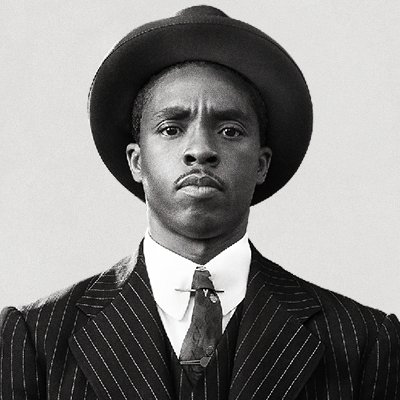

Adrian Piper is a white-looking black woman. Not surprisingly, race and gender have been two of her lifelong preoccupations, but that doesn’t mean she falls into a presumed political category. Instead Piper seems to know more about “our fishbowl” because essential parts of her have spent so much time outside of it. As a result, she’s ended up approaching nearly everything “her way.”

Adrian Piper is a white-looking black woman. Not surprisingly, race and gender have been two of her lifelong preoccupations, but that doesn’t mean she falls into a presumed political category. Instead Piper seems to know more about “our fishbowl” because essential parts of her have spent so much time outside of it. As a result, she’s ended up approaching nearly everything “her way.”

And that, I think, is why she’s useful for us to turn to as we face the gap that’s been left by the social institutions that once helped shape our convictions. Piper has figured out how to sponsor her own dialogue about what’s important and what’s not with the wider world—and then to tell us about it.

Piper went to art school in New York City at the end of the 1960’s. Over the next ten years her texts, videos and performance art aimed at challenging viewers and readers to take a clear-eyed stand for themselves. For example, she often used her own body as a primary image for unannounced public performances, such as walking City streets soaked with wet paint or wearing an Afro wig, fake mustache and mirrored sunglasses to confront people with the stereotype of a young aggressive black male whom she called the Mythic Being. During this time, Piper also got her doctorate in philosophy from Harvard. She has been producing works of art and philosophy ever since.

Piper went to art school in New York City at the end of the 1960’s. Over the next ten years her texts, videos and performance art aimed at challenging viewers and readers to take a clear-eyed stand for themselves. For example, she often used her own body as a primary image for unannounced public performances, such as walking City streets soaked with wet paint or wearing an Afro wig, fake mustache and mirrored sunglasses to confront people with the stereotype of a young aggressive black male whom she called the Mythic Being. During this time, Piper also got her doctorate in philosophy from Harvard. She has been producing works of art and philosophy ever since.

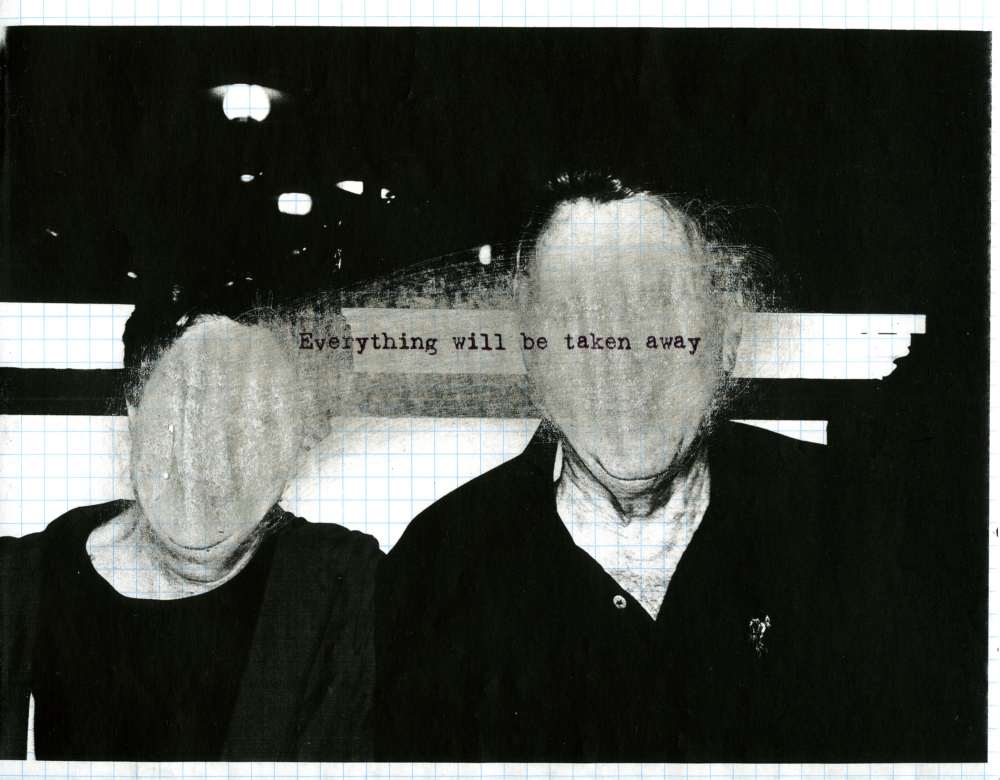

In a 1981 essay called “Ideology, Confrontation and Political Self-Awareness,” Piper discussed concepts she explores through her art and later expanded upon in her 2-volume “Rationality and Structure of the Self, published in 2009 and 2013, respectively. At the great risk of over-simplifying what she has to say, a key theme is that our beliefs (or ideologies) go unquestioned until they are attacked by new experiences that introduce doubt. Oftentimes, we either don’t allow our cherished beliefs to be interrupted by doubt or aren’t aware enough to realize that they have been undermined. According to Piper, doubling-down and obliviousness are responsible for “stupid, insensitive, self-serving [behavior], usually at the expense of other individuals and groups.” Her antidote is acknowledging these doubts and continuously questioning our beliefs: a kind of moral nakedness.

I can’t do justice to Adrian Piper’s art or philosophy here, but I hope you’ll be intrigued enough to explore both of them further. The following quotes, from an interview she gave when her exhibit opened at MOMA, may help in peaking your interest.

Truly Opening Your Mind in the Face of Someone Else’s Arguments

To really read any discursive text… is a disturbing and cognitively disorienting experience, because it means allowing another person’s thoughts to intrude into your own and rearrange your beliefs and assumptions — often not in ways to which you would consent if warned in advance. Even when you deliberately decide to learn something new by reading, you put yourself, your thoughts and your most cherished suppositions in the hands of the author and trust her or him not to reorganize your mind so thoroughly that you no longer recognize where or who you are. It’s very scary; hard, painstaking work of determined concentration under the best of circumstances. So particularly with philosophical texts, the whole point of which is to reorganize your thinking, people often don’t really read them at all; they merely take a mental snapshot of the passage that enables them to form a Gestalt impression of its content, without scrutinizing it too closely.

Second-Guessing Your Own Judgments (and Why Women Are Particularly Good At It)

As an attitude…epistemic skepticism consists in always second-guessing your own judgments — about yourself, other people and situations; always monitoring those judgments to make sure you’re seeing clearly, have the facts right, aren’t making any unfounded inferences or deceiving yourself, etc. Women are particularly skilled at this because their judgment, credibility and authority start to come under attack during puberty, as part of the process of gender socialization. They are made to feel uncertain about themselves, their place in society and their right to their own opinions. If that socialization doesn’t work, they can’t be made to obey, to defer and to depend on others to make important decisions for them. Obviously this is a horrible, misogynistic practice, now known as “gaslighting” after the 1944 George Cukor film. But the benefit is precisely this self-critical attitude — of careful review of and reflection on the adequacy of one’s own thought processes.

For several years, Piper challenged the orthodoxy of how philosophy was written and taught in the U.S., and suffered both academically and personally for the stands that she took. Today she lives in Berlin.

Adrian Piper’s Most Important Achievements

I can name four off the top of my head:

(1) To have taken care of my mother during the last two years before her death from emphysema.

(2) To have escaped from the United States with my life.

(3) To have successfully treated most of my post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms myself, by writing “Escape to Berlin.”

(4) To have finished “Rationality and the Structure of the Self “at the same standard of quality I apply when I criticize other philosophers’ work — thereby demonstrating to my own satisfaction that it is not an unrealistic or impossible standard to meet. Of course you do have to be willing to get kicked out of the field in order to meet it.

It is essential to have social institutions like churches and schools to build and test your convictions. But it is also possible to do some of that work on your own, as Piper has done. It involves presenting yourself to others honestly and forthrightly (her art), always second-guessing your beliefs (her skeptical attitude), and using a journal or other kinds of writing to see your way through the triumphs and disappointments of living a good life (her books).

(This post was adapted from my July 22, 2018 newsletter)