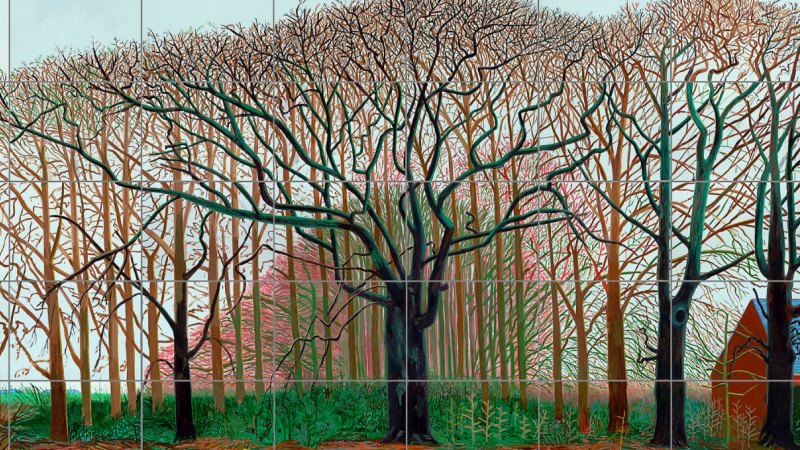

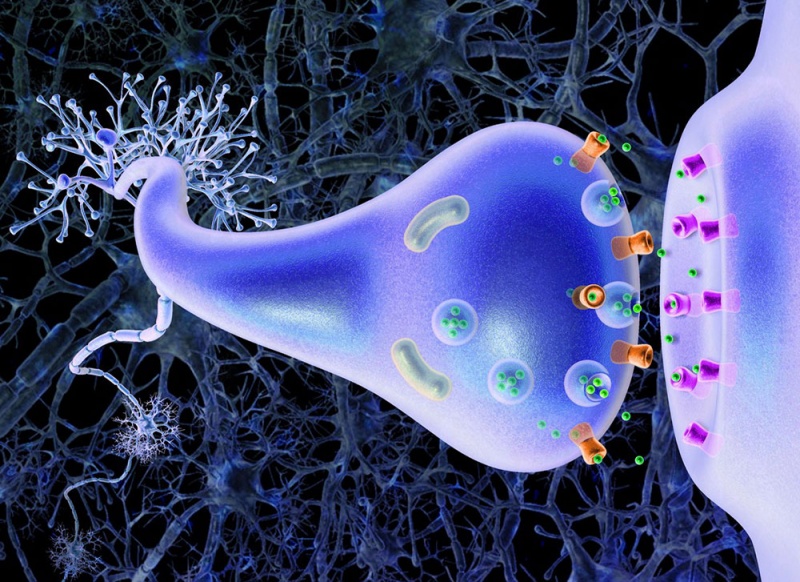

“Embodied knowledge” is a kind of understanding where the body knows what is happening, and sometimes even how to react to it, without really thinking about it. There is no need to verbalize or connect a string of thoughts. You just know or “feel it in your bones.” It happens via the neurotransmitters in our brains, as depicted in the striking image above by Arran Lewis.

Here are some examples of embodied knowledge:

– I’ve already learned how to distribute my weight on the seat of a bike, put my feet on the pedals, lean forward, so I no longer have to think about how to do it, I just know how get on my bike and ride.

– I know that when I get a certain kind of headache, a high-pressure weather front is moving in and I need a pain reliever. My head is like a barometer “automatically” telling me what to do.

– A farmer nearby might know from the way his chickens are acting or his kids are behaving that the run-off from a nearby plant has been getting into their water, whatever the township or elected officials are saying about it.

It’s the kind of knowledge that internalizes complicated experiences without the need for an elaborate thought process.

This last example of embodied knowledge—where a deep understanding of the land and the people and fauna that live there differ from what the authorities are telling you about it—has been Kate Brown’s preoccupation for much of the past twenty years.

Brown is a professor at MIT, interested in “where history, science, technology and bio-politics converge to create large-scale disasters and modernist wastelands.” She is a storyteller who has put herself into her stories so she can interview and experience the lives of people with “embodied knowledge” in places like Chernobyl and the Nevada dessert after terrible nuclear accidents. From their first person accounts and her reactions to them, she identifies discrepancies from the expert “investigations,” challenges the official narrative once politicians get involved, and shows how the embodied knowledge of those affected by disasters resonates beyond the borders that we usually place around them.

This week, I heard Brown speak about her work as part of a interview series sponsored by Duke University. That continuing series explores ethical responses to The Anthropocene, or the time in Earth’s evolution where human forces have matched (or overtaken) natural forces in determining the fate of the planet. The Series question to Kate Brown and others has been: What can we, what should we be doing about it?

Brown’s most straightforward answer would be: listen to the people with embodied knowledge. The people who are “closest to the ground of disaster” can tell us much that we need to know about how to deepen our own sense of place in order to survive in a world that has already entered a kind of death spiral. Their world of disaster is increasingly our world too. The ways that embodied knowledge have been gained in Earth’s disaster zones can become a kind of template in our own quests to survive in environments that have been degrading more rapidly than most of us would like to admit.

Kate Brown’s books have won a cascade of awards for history writing and non-fiction. They include: A Biography of No Place: From Ethnic Borderland to Soviet Heartland (2004); Plutopia: Nuclear Families in Atomic Cities and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters (2013); Dispatches from Dystopia: Histories of Places Not Yet Forgotten (2015); and her acclaimed Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future (2019).

I found three things about Kate Brown’s life and research to be particularly noteworthy. First, why has she focused her work on the embodied knowledge of people in disaster zones? (My real question: how do people find their work priorities?) Secondly, as I’ve been thinking about deepening my own “sense of place,” I was fascinated by the role that specific environments and peoples’ deep-seated knowledge of their places play in Brown’s history-writing and storytelling. And lastly, because Brown has traveled to and reported from Earth’s calamitous edges—she calls herself “a professional disaster tourist”—I wondered some more about the message that she’s been carrying back for the rest of us.

What can or should we be doing in order to survive?

Why any of us gravitates towards the work we end up doing may itself be explained by a kind of “embodied knowledge.”

For Kate Brown, I wondered what it was in her experience that made her seek out people who were burdened by the nuclear catastrophe at Chernobyl or the plutonium incidents in Nevada where (according to her) the fallout of “radioactive iodine from atmospheric detonations of nuclear bombs dwarfed Chernobyl emissions three times over”? Clearly, it was not the origin story of someone who would automatically believe that Soviet propaganda is more misleading than the American variety.

Brown’s formative years were spent in a small Midwestern town that was gutted after its economy collapsed. She literally grew up among its ruins. As Brown recounts:

The year I was born, 1965, the Elgin watch factory [in Elgin, Illinois] shuttered, and they blew up the watch tower. It was a company town, and that was the main business. I grew up watching the supporting businesses close, and then regular clothing stores and grocery stores went bankrupt.

It was nothing near what I describe in wartime Ukraine, or Chernobyl, or one of [the] plutonium plants, but I finally realized I was so interested in modernist wastelands because of my own background.

Before she was born, Brown’s mother had already moved four times because of “deindustrialized landscapes,” and her parents “moved to Elgin thinking it was healthy, small-town America. So how many times do they have to jump?…What if you care about your family and [your] community” and didn’t want to abandon them? So she gravitated towards groups of people who stuck it out in the much the same way that her family did.

The drive behind Brown’s work made me think about naturalist and writer Barry Lopez, who has also chronicled our impending environmental disaster. Only in 2013, towards the end of his long career, was he able to describe how he’d been repeatedly victimized as a child in a Harpers magazine article. He told us that the “sliver of sky” in its title was what he was reaching for in his own work from “the edges of our throttled Earth,” an unwaivering attempt “to find a way to turn the darkness [he’d experienced himself] inside out.”

In her stories about other places that have been grievously injured, I was also reminded of Arlie Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land. Not only do the Americans who live there deserve our understanding during this politically divisive time, but Hochschild’s approach as a sociologist to those who live in the most damaged parts of Louisiana, is startlingly similar to Lopez’s as a naturalist and Brown’s as an historian. Each of them put themselves in the stories they are telling, frankly acknowledging their personal perspectives as interviewers and interpreters, while (in the process) giving their audiences narratives that are intimate and involving precisely because of the personal roles they have chosen to play in them.

Brown, Lopez and Hochschild have been continuing to write their own stories as they invite the rest of us into them.

Many of you know that I’ve been thinking a great deal about “sense of place” recently. (Last week, I gave my reactions to the movie “The Dig” and its meditations on what any of us might want to preserve in the face of disaster, like these Englishmen and women were doing before the bombing of Britain in World War II. In mid-December, I ruminated about how the places where we live and work become more meaningful as we learn how to capture and retain their most vivid memories.)

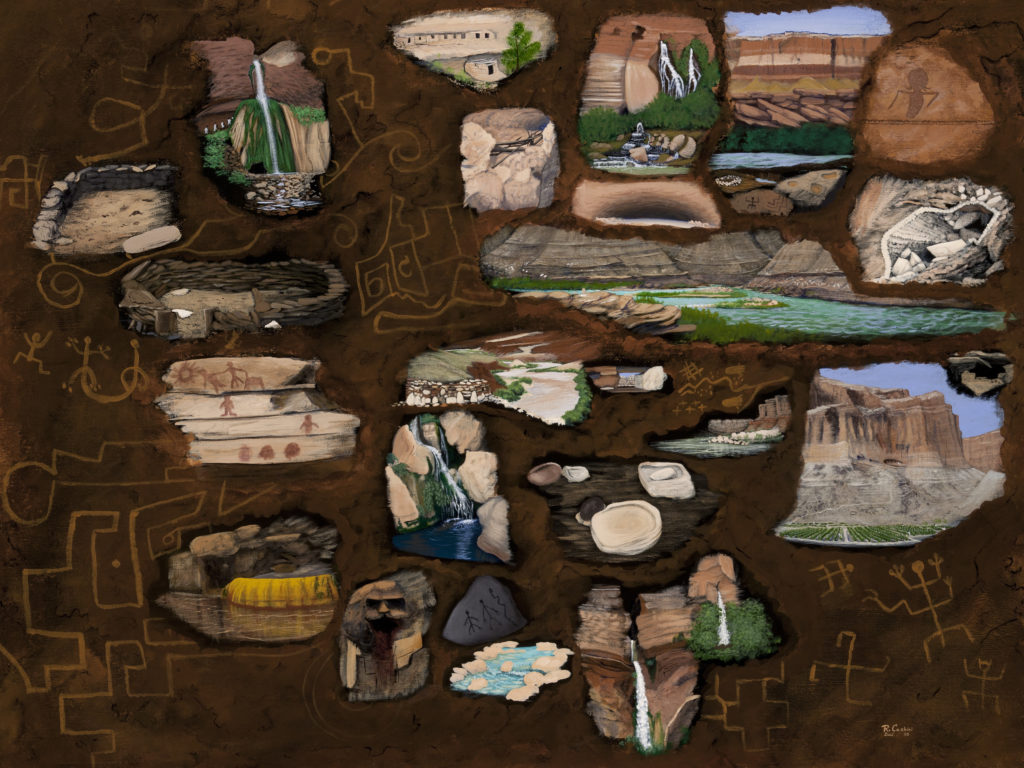

Something about “sense of place” for Brown can be understood from the images in her book titles: No Place, Borderland, Dystopia. The places she’s explored have been the toxic waste dumps of industrial civilization. The area around Chernobyl is called Polesia, swamplands populated by a mix of Poles, Germans, Jews and Ukrainians that was either forgotten or dismissed by the urban centers of Kiev and Moscow, with few outsiders expressing any interest in what its people had to say for themselves. Brown did listen, recognizing their “embodied knowledge” when they described what was happening to them, introduced her to their “radiant children” (or those who’d been stunted by radiation), and told her how they continued to survive in a contaminated landscape that the “outside world” wanted everyone to believe had fully recovered.

In one poignantly conflicted moment, Brown describes the tremendous generosity of a local family as they offered to share their homegrown feast with her and her reluctance to eat it and appear ungracious because she knew how contaminated by radiation the region’s entire food chain had become. With images like this, Brown argues that “what it means to be human” in places like this is different than anything we have ever seen before, and that as the climate and Earth begin to change in equally profound ways, what it means for the rest of us to be human is already changing too.

(For example, while Brown doesn’t recount them, think about how many weeks earlier the Spring will be coming this year than it did only a few years ago. Think about how much less snow there is on the ground or ice on the ponds in Northern states than we remember as kids during this time of year. Think about birds and animals you no longer see in your backyards. Think about how many more 100+ degree days there will be in Arizona this summer than there were only 10 or 15 years ago, or how many more deadly wildfires in California.)

How we experience the degrading nature of the “places” where we live and work profoundly affects us in ways that have much in common with the residents of Brown’s Polesia. But unlike many of us, Brown’s Polesians had gained an embodied kind of knowledge about what they’ve been experiencing. They’ve had to in order to survive. Farm animals became their Geiger counters (as in, “the cows have been acting funny”). Brown is astonished by how women at a local textile plant have learned how to attribute various aches and pains that they experience to particular isotopes lodged in specific organs of their bodies.

We will be gaining that kind of experienced knowledge too—knowledge that’s tied to the ground of our particular “places” as global warming affects them. We’ll need to deepen our sense of place in an embodied way too.

So what does Brown recommend, what else does she think we should be taking away from (and perhaps applying) after her deep, long look into the hinterlands of disaster?

I believe she’d say that it’s the practical guidance we can take from people who have learned how to cope in profoundly compromised environments. It’s more of their kind of “embodied knowledge”–and maybe less of what the experts and politicians have to say about what’s happening around us– that needs to be our guide.

In the way she has approached her history-writing, Brown also offers a counterweight to the obliviating impact of “contested knowledge.” About the farmers and factory workers around Chernobyl she notes:

These people got cancer, these kids have cancer, but we don’t know for sure what caused it.’ I saw how those statements of scientific uncertainty drilled down, undermining the claims of people whose families were riddled with illnesses. Rather than report two sides of a controversy (there are always far more than two sides), I wanted to leave the reader with an informed judgment. As I write in the first person, it’s clear that this is my studied opinion.

Brown’s role in determining the credibility of those she interviews and telling us why she believes them, effectively validates the “embodied knowledge” gained by these victims instead of leaving them in a further hinterland of sorts—one that’s in the shadows beyond credibility—because scientists or government officials lack the time, the money or the commitment “to connect and prove” each toxic cause they claim to each damaging effect. In other words, experts and politicians don’t need to confirm what your experience at surviving tells you to rely upon; they don’t necessarily “know any better” than the folks who are aready doing the hard work of surviving on the ground.

An essay comparing various Chernobyl accounts to HBOs 2019 dramatization also discussed how Brown’s “putting herself in the story” allows her to involve readers and listeners in what she’s saying by provoking us to formulate our own perspectives on the events she describes. She tells us her opinion about what farm and factory workers are claiming as well as why she believes them by (for example) referring to records she’s uncovered, and by doing so, invites us to have our own opinions about their testimony.

Crucially, Brown’s interjections of first-person narration are not merely ruminative or speculative. Rather, they are constructed to prompt the critical capacities of a reader who is invited to think with the author through a literal and metaphoric journey that begins with and eventually goes beyond the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

By choosing this almost interactive approach, Brown’s storytelling method not only “prompts” our critical capacities involving Chernobyl, it also invites us to bring the same faculties to places far closer to home (like the Nevada contamination sites that are far less known but even more toxic) or to the negative impacts of impending climate disaster that we’re experiencing in our own backyards. We can become more like actors in (and less like the passive victims of) the place-driven stories that we’re in.

Barry Lopez–who also put himself in his stories–seemed less hopeful than Kate Brown that all of us can be mobilized in time to confront the unfolding climate crisis. Writing about his final book called Horizon, I described the smaller group of actors that he hoped to enlist, but it was never in doubt that he also believed (along with Brown) in the power of hard-won, localized wisdom to help us through the difficult days ahead.

Lopez seems less certain that he can reach the tourists in their lounge chairs around the pool and more reliant on networks of wisdom that still include his ‘family, friends, mentors and professional colleagues’ but now depends at least as much on the wisdom of traditional cultures that have found ways to survive in the face of war, environmental destruction and natural disaster. Unlike citizens of the developed world who act like children looking for heroes to save them, for thousands of years adults who know how to make decisions to care for everyone and ensure that no one gets left behind have guided [what he calls] ‘heroic communities’ of indigenous people across the world. Today, Lopez tries to counter his doubts by imagining networks comprised of all the different communities that depend on adults with the knowledge to survive so that we can claim our uncertain future together.

In the hinterlands of our civilization—where we’ve dumped our refuse and conducted the industrial experiments that help us support our consumer-driven economies and comfortable lifestyles—there are people who have learned and are continuing to learn how to survive in places that many of us would rather forget. As a contrary voice, Brown says loudly and clearly (along with Lopez and Hochschild): Come with us, use your imaginations to become involved in these frontline stories, and perhaps you can also figure out what you need “to know now” and “do now” in order to survive.

This post was adapted from my February 14, 2021 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning and occasionally I post the content from one of them here. You can subscribe too by leaving your email address in the column to the right.