Our expectation that we’ll always pay less for consumer products has an impact on the people in the supply chain who bring us those products—and it’s not a good one.

I’m talking about those who mine the metals in your cell phone, pick the cotton in your socks, process the rubber in your running shoes. It’s the workers in places like Indonesia or Peru who put your toaster together, stick the pins in your dress shirt so it looks good in its package, or pack the parts you’ll assemble into an IKEA bookcase. Finally, it’s the American sales clerks, service managers, stock boys and checkout girls who get the final product into your hands.

To bring you “everyday low prices,” the people in these supply chains are paid “as little as their labor markets will bear” so that the factory owners, shippers and ultimately the stores you shop in can make a profit when you open up your wallet. With fewer dollars to go around and cutthroat competition between the on-line and bricks&mortar stores, every link in the consumer product supply chain is squeezed. This includes workers along the arc of production—including those in America.

How is our addiction to cheap stuff making the work that many of our neighbors do everyday a losing proposition—and why should we care?

At one level, this is how capitalism is supposed to operate. Workers trade their labor for wages, and the owners figure out how to make a profit after the labor and other costs of doing business are covered. In competitive markets, this means that there is constant pressure to produce as cheaply as possible. Manufacturers flee the US for cheaper labor in Mexico or Bangladesh, and as wages rise in those places, to even poorer countries with “surplus workers” for hire. American factories close because it costs so much less to make your shirt or toaster somewhere else.

But millions of Americans still staff the big box stores where you’ll likely buy that shirt or toaster this year. Over the years, we have grown accustomed to “the cheap foreign labor dividend” that enables us to pay less and less when we go shopping for consumer products. But there are only so many savings to be realized from cheap labor abroad. At some point, full-time American workers in this supply chain also get squeezed, often to the point where they can no longer live on the money they earn.

There are “acceptable” and “unacceptable” efficiencies in capitalism.

For example, you can’t make shoddy merchandise because it won’t sell in most markets. Child labor, sweatshops, safety and health risks, damage to the environment are also unacceptable (at least when it comes to making something in the U.S.). But what happens when all of the “acceptable” efficiencies have been obtained, and only “unacceptable” ones remain?

When it comes to many of our consumer products, we have already crossed that divide today—and our expectations as consumers have a lot to do with it.

Wal-Mart was a revolutionary company because it mastered the art of selling products to consumers more efficiently than they had ever been sold before. As discussed in a recent Atlantic article by Jordan Weissmann, it paid its workers so little that they had no alternative but to shop at discount stores. . . like Wal-Mart. However, it didn’t end there. Many full-time jobs at Wal-Mart and other big box stores barely take a family of three over the federal poverty line. These retailers are simply not paying most of their workers enough to live on, what we call “a living wage.”

Ultimately, this all comes back to consumers. We are the ones who choose where to take our business. And for the most part, Americans have chosen cheap.

It’s hard to blame middle class families for making that decision—not a lot of people have the extra cash to make a political statement out of where they buy paper towels and diapers. But it’s led to cycle of [worker] impoverishment….

Economists have considered what it would cost to break this cycle, and it turns out that the cost to us would come pretty cheap. Weissmann cites a study by UC-Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education suggesting that it would cost the average shopper only $12.49 more a year if Wal-Mart paid its workers a living wage.

So the questions remain: what’s to be done about the human cost of everyday low prices? And why should any of us care?

Most of us will voice our opposition to merchants paying full-time American workers less than a living wage, but our abstract moral concerns are trumped—almost every single time—by the consumer product we want and the low price we want to pay for it. So even if a wave of the wand could make it happen, would our behavior change if the trade offs were more explicit to us as consumers?

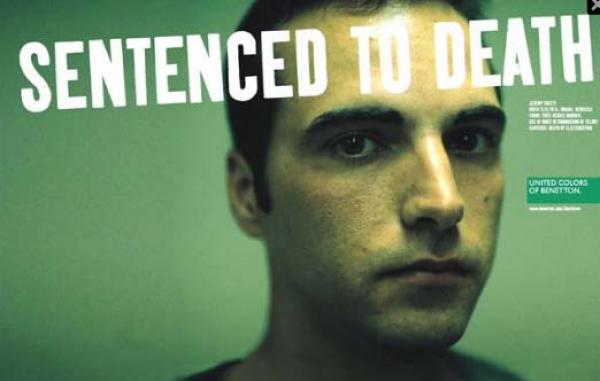

- Such as a sign you see before entering the big box store that says: “Be willing to pay a little more so that the workers here can get a paycheck they can live on.”

- The checkout girl wearing a badge that says: “Your addiction to everyday low prices means I can’t support my family.”

- Would realizing that the person harmed is standing in front of you be enough to get you to shop at the mom & pop store that charges more so it can pay its employees fairly?

- Would coming face-to-face with the social cost of consumer economics lead you to add a few bucks to your checkout bill, like a “tip,” for the “Big Box Employee Living Wage Fund”?

At the very least, the realities of our addiction to low prices and its human costs need to become more personal as close to the point of purchase as possible. That said, while there is always hope that the situation could change someday, there’s hardly cause for optimism if the consciousness raising goes no further than this.

What’s also needed is an understanding of why changing this value proposition in our consumer driven economy is important to you and the value of your work?

When some workers in your community are treated like property, it is easier for your employer to treat you that way—an economic instead of a human resource, little more than a cog in a wheel. As more and more full time, middle class jobs are lost to “the knowledge economy,” and more work is assigned on a part-time, piecemeal basis, it will become harder for any of us to make a living wage. Self-interest may lead us to start demanding that every single full time worker in America is making enough to live on.

It is also about community. The consumer product workforce is comprised of your family members and neighbors and people you see all the time. They don’t or can’t “move on” to better jobs, because increasingly those “better” jobs are unavailable. As an increasingly permanent part of our way of life, they are connected to you and to me, and have a face.

As we put our economy back together, there is an opportunity to rebuild our communities around the work that each and every person in it does. But communities where every worker is appropriately valued will never be possible until we confront our addiction to consumer prices that are lower than they have to be.

A version of this post also appeared on Marc Gunther’s Business & Sustainability Blog, where it provoked a range of comments.