It’s a kind of truism for a democracy like ours: When we’re divided we fall.

We’re not at that precipice, but it sure feels closer. In my feelings about how likely the danger really is today, I’m grateful to have traveled around this country and to have spent time in places like Missouri and Wisconsin so that I know such places as more than fly-over country and their inhabitants as people who are not that different from me.

In an important recent essay that we’ll get to in a minute, Jonathan Haidt describes these folks (who are, in fact, most Americans), as “the exhausted majority,” tired to the point of retirement of all the noisy damage from the progressive and MAGA extremes that tend to monopolize our airways and screen time. I remember meeting many of these same people when I was just a kid. Back then, they were called “the silent majority,” and while they might have seemed more prominent in places like the Mid-West, I think that’s just because they weren’t so easily obscured by the “always on” self-promotion that blares from media centers on the Coasts and from a few big cities in the middle.

I know that these Americans are everywhere because I’ve come to know many of the “silent and exhausted” as my neighbors in what otherwise seems like the bluest of blue cities. They’re here, they vote, they’re concerned, involved and a check on even Philadelphia’s excesses. Indeed, it’s the volume, the sanity and the decency of America’s vast waistline that keeps our feet (as a nation) on the ground and our head a lot clearer than it would otherwise be.

We’d be closer to the precipice without them. At their best, they operate like an anchor against our worst political impulses.

It’s the volume, sanity and decency of America’s vast waistline that keeps our feet (as a nation) on the ground and our head a lot clearer than it would otherwise be.

Some of my closest encounters with “just plain citizens” have happened in jury rooms. As a lawyer, I’m always surprised when I get accepted onto a jury (I recall a time when my profession was an immediate disqualifier) but now I get on panels routinely and, once I do, I try to melt into the crowd, someone whose expertise is a resource instead of an excuse for having a weightier point of view. From inside that room, I’ve been repeatedly reminded of what our forebears in English jurisprudence had discovered about juries: their power to project a community’s values and good sense onto a set of circumstances—in other words, to figure out “what happened” and “what society should do about it” by demonstrating their collective wisdom.

Serving as a juror has become one way to remind myself about the arrogance and elitism of professional classes and experts that think they “know better,” and it’s always been a rejuvenating way to re-involve myself in my community (“Jury Duty Is a Slice of Life That You Want to Have”). Wearing a juror badge a few years back also got me thinking about another civic commitment that can bind instead of divide us from most other Americans, namely thinking (in the sense of deliberating) about the dollars-and-cents investments that we make in our local, state and federal governments when we pay our taxes (something discussed in last week’s post “I Could Turn Myself Into a Tax Deduction (or Then Again, Maybe Not)”) Don’t I want to make wise, as opposed to mindless investments in my country, and aren’t those investment decisions worth talking about with others who are making them too?

There’s another area where we’ve lost but could easily recover our sense of community. The personal and financial burdens of America’s war-making would almost certainly be borne more equally—and at least some of our foreign wars might not be fought at all—if instead of being waged by a proxy army of “volunteers” with few other options, our military ranks were comprised of everyone’s children via a “universal” draft. Without that common investment, wars in places like Afghanistan are simply abstractions for too many until we’re confronted with a debacle like the evacuation of Kabul last summer. (In this regard, you might want to check out Andrew Bacevich’s Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country.) These are all places where Americans are meeting today—or could be meeting—across their divides.

Greater participation in civic commonalities like jury duty, tax paying, war-making and avoiding would all help to bind our communities together. National disasters can too. I’m thinking about the ways that “regular” people came together in ways that neither government nor governmental authorities (like FEMA or the CDC) could manage in the wake of 9/11 or the recent pandemic. In the later, the essential workers that we celebrated as heroes were regular folks who weren’t tweeting about their accomplishments or sacrifices, they were simply showing up to some very hard jobs day after day. (As I’ve mentioned here before, Rebecca Solnit writes magnificently about the everyday people who did the same after 9/11, Hurricane Katrina and similar catastrophes in A Paradise Built in Hell: the Extraordinary Communities That Arise In Disaster.)

These are places where Americans are meeting today—or could be meeting—across their divides.

But while regular/silent/exhausted/essential/middle Americans are surely a corrective in a democracy like ours, they may not be able to produce enough “spontaneous and timely” action to keep us from the precipice that we still seem to be heading towards. It’s out of that concern that Haidt, a social and moral psychologist at NYU, wrote an excellent article in the April 2022 issue of The Atlantic called “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.” You need to read it, because no summary of it that I can give here will do it justice. (If you confront a paywall in your efforts to do so let me know and I’ll get you a copy.) You also need to read it because despite its look-twice-at-it title, Haidt makes his argument for confronting our stupidity astutely and methodically, because perhaps more than any other critical observer, Haidt has been struggling to explain and then reduce our values-driven polarization since his ground-breaking The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion almost ten years ago.

In his Atlantic essay, Haidt’s argues that the confluence of social media platforms and trends in our politics have brought us closer to the edge as a cohesive nation than we have been since the Civil War. Because I’ve not seen this urgency expressed so simply, straightforwardly and elegantly before, I’ll highlight a couple of pieces of “evidence” that he cites (because they made better sense to me when viewed in his wider context), but I won’t attempt to summarize the entire waterfront that he covers here.

We all need to struggle against the stupidity that increasingly confronts us in our daily attempts to make sense of it all. His argument (which includes proposed “solutions,” that are brilliant in their modesty, nuance and precision) may be the perfect place to start.

The social media megaphone with some of its tokens of our current “stupidity,”

according to Haidt.

The childlike innocence of emojis that express our approval or disapproval, our “liking” and then retweeting or “sharing” what we like, all appear to be pretty benign, at least at first. But given the state of our politics in, say, 2011, these simple emotional messages on social media were anything but when they dropped, unannounced, into our lives.

I remember something about the state of our affairs 10 years ago. For one thing, while the Great Recession had happened in 2008 and 2009, for many businesses (including this family’s) its most challenging consequences were only felt years later, from 2011 on. At the same time, the US was still mired in two wars—first Afghanistan and then Iraq—and the political divisiveness around Bush-era decision-making in those wars and, to a somewhat lesser extent, from FEMA’s bungling after Katrina in New Orleans, had failed to produce a new consensus around Obama’s presidency, as we were soon to discover in the awkward launch of “Obamacare” in March of 2010 and the rise of the Tea Party in the mid-term elections of 2012.

Into this increasingly turbulent political landscape, a couple of seemingly modest, “user-friendly” innovations were introduced on social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. Perhaps it took a social psychologist like Haidt to recognize how efficiently “emojis, likes, retweets and shares” divided the world between “good” and “bad” and how effectively they amplified the morally-charged and highly-emotional judgments of a very small group of political partisans for the first time in the history of communication.

In other words, something entirely without precedent in human social, cultural, political and psychological experience had happened, and only now are we identifying the root causes as we confront the damage that’s been done in the intervening years by the Far Left and Far Right.

The first thing that Haidt’s essay managed to crystallize for me was how small groups of highly motivated people at both ends of the spectrum succeeded in polarizing the entire political debate by additional orders of magnitude, and the kind of narcissism that drove these small numbers of people when they had the opportunity to exert their influence over almost everybody else.

My second revelation was how vulnerable we are when it comes to governing ourselves given the foundations that are essential to cohesive decision-making in a democracy like ours, particularly when we’re confronted with the rise of new technologies and global conflicts that are likely to present further challenges of an existential nature to “our way of life.”

These arguments about manipulation and urgency of the moment are why we should all care about this. Let’s consider Haidt’s words in these regards.

Around 2011, a small group of people who aspired to be “thought leaders” saw the self-promotional value of new social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter:

they became more adept at putting on performances and managing their personal brand[s]—activities that might impress others but that do not deepen friendships in the way that a private phone conversation will.

Once social-media platforms had trained users to spend more time performing and less time [actually] connecting, the stage was set for the major transformation…the intensification of viral dynamics. [the italics are mine]

With “like,” “re-tweet” and “share” buttons fully deployed, the social media platforms developed algorithms that could put in front of each user the kind of content that could generate her “like” or encourage him to immediately “share” what he’d seen with others. The social scientists who guided the design of these algorithms soon had research in hand which proved that the posts that triggered emotions—especially anger directed at perceived enemies—are the posts that are most likely to be shared. Helping to prove his “they’re making us stupider” thesis, Haidt notes:

One of the engineers at Twitter who had worked on the ‘Retweet’ button later revealed that he regretted his contribution because it had made Twitter a nastier place. As he watched Twitter mobs forming through the use of the new tool, he thought to himself, ‘We might have just handed a 4-year-old a loaded weapon.

As Haidt goes on to explain: “[t]he newly tweaked platforms were almost perfectly designed to bring out our most moralistic and least reflective selves” given the expedited ways we could now endorse an inflammatory message and spread it around. The question, of course, is whether our democratic institutions and our on-going conversations as citizens are resilient enough to survive this kind of barrage.

According to Haidt, the pied pipers who lead this destructively stupid parade are drawn from of a very small number—less than 15%—of America’s population.

The ‘Hidden Tribes’ study by the pro-democracy group More in Common, surveyed 8,000 Americans in 2017 and 2018 and identified seven groups that shared beliefs and behaviors. The one furthest to the right, known as the ‘devoted conservatives,’ comprised 6 percent of the U.S. population. The group furthest to the left, the ‘progressive activists,’ comprised 8 percent of the population. The progressive activists were by far the most prolific group on social media: 70 percent had shared political content over the previous year. The devoted conservatives followed, at 56 percent.

These two extreme groups are similar in surprising ways. They are the whitest and richest of the seven groups, which suggests that America is being torn apart by a battle between two subsets of the elite who are not representative of the broader society.

What’s more, they are the two groups that show the greatest homogeneity in their moral and political attitudes. This uniformity of opinion, the study’s authors speculate, is likely a result of thought-policing on social media: ‘Those who express sympathy for the views of opposing groups may experience backlash from their own cohort.’ In other words, political extremists don’t just shoot darts at their enemies; they spend a lot of their ammunition targeting dissenters or nuanced thinkers on their own team. In this way, social media makes a political system based on compromise grind to a halt.

In addition to being lethal weapons in their own right, the weaponizing of uncivil discourse is likely to get worse in coming years. New technological advances and bad actors in places like Russia and China who see an upside to themselves in destabilizing America will see to that.

These arguments about manipulation and the urgency of the moment are why we should all care about this.

On the new technology side, Haidt reports that “artificial intelligence is close to enabling the limitless spread of highly believable disinformation.” (Indeed, in many places it already seems to be doing so.) Moreover, advances in the art of “the deep-fake” will make it more difficult to disbelieve our eyes when we see a deliberately altered and misleading image pop up on our screens.

There will also be implications for America’s ability to “hold its own” in the face of an increasingly hostile world.

We now know that it’s not just the Russians attacking American democracy. Before the 2019 protests in Hong Kong, China had mostly focused on domestic platforms such as WeChat. But now China is discovering how much it can do with Twitter and Facebook, for so little money, in its escalating conflict with the U.S. Given China’s own advances in AI, we can expect it to become more skillful over the next few years at further dividing America and further uniting China.

How close do we have to get to the precipice before we’re mobilized to do something about it—not through government necessarily, but as citizens who can speak out and mobilize from our silent/exhausted/essential/ middle, that is, in the voice of our vast majority?

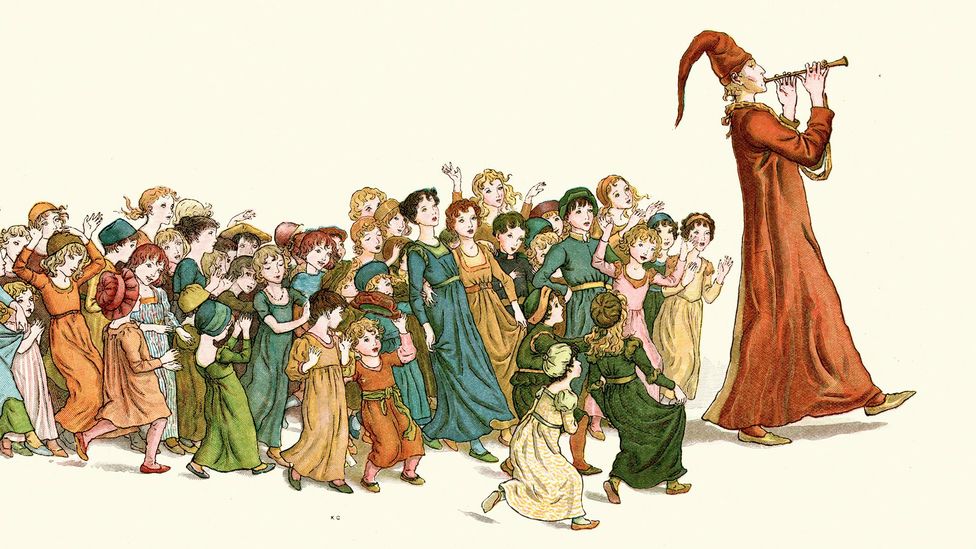

The Piper had taken out the rats before he took out the children.

I led off with an image of the Pied Piper (up top), trailed by his captivated young followers, who were being lured from town by the Piper’s malice after the townspeople had failed to pay him for his earlier work, which was to lead the town’s rats to their eventual demise.

It’s a chilling story, originating in medieval German folkfore, picked up by Goethe in Der Rattenfanger, the Brothers Grimm in a cautionary tale, and Robert Browning in one of his poems. Entranced by the brain-dulling notes of his flute, both the town’s rats and eventually its children are led to their doom. In the process, the Piper becomes a universal bogeyman, “one very grim reaper,” who uses his seductive wiles to administer some very final consequences.

His mind-dulling ways seem relevant here too.

Whether we are “on social media” or not, millions of us are caught up in the emotionally charged messaging that blares almost constantly from its direction. Just listen for the extremist din around “Roe vs. Wade” this week, or about Clarence Thomas’s or Anthony Fauci’s “lack of objectivity” last week.

Today’s pied pipers on the Left and the Right adroitly hook us through our confirmation biases, which are our tendencies to always be on the lookout for evidence that confirms our preferred beliefs and ways of understanding all manner of things. It’s a tendency that makes us “stupider,” according to Haidt, because “[t]he most reliable cure for confirmation bias is interaction with people who don’t share your beliefs” [italics mine]. Unsurprisingly, it’s also the most reliable way to get smarter.

Moreover, the extremists’ self-policing tendencies on social media—their constantly ferreting out deviators from their perceived orthodoxies, whether “woke” or “MAGA” in nature—have a milder, but still perceptible impact on the rest of us too, who gain some easy comfort from affiliating with our perceived tribes. For while these inquisitions to enforce “true beliefs” are most damaging to the small minority of extremists, it’s almost impossible to escape their toxic effects. As Haidt writes:

People who try to silence or intimidate their critics make themselves stupider, almost as if they are shooting darts into their own brain.

In other words, the darts we’re shooting at ourselves to align with our tribal instincts have their own detrimental effects. In Haidt’s parlance, as all this conformity is making us stupider, the internal threats (from tech advances) and external threats (from hostile adversaries) are getting more worrisome.

“The most reliable cure for confirmation bias is interaction

with people who don’t share your beliefs.”

In a post here from several months back (“The Way Forward Needs Hope Standing With Fear”) I discussed a lesson from Buddhist Pema Chodron, who (at 85) is the principal teacher at Gampo Abbey in Nova Scotia. With hope as we usually understand it, there is always a fear that whatever you long for won’t come to pass, Chodron says. But accepting that your hope is always bound up with your fear can liberate you from fear’s constraints, because instead of being tentative or even paralyzed by your alarm about the future, it is possible to generate as much curiosity about your fears as you have about your longings. It’s cultivating your curiosity about what you dread that can loosen fear’s disabling hold.

I hope you find, as I did, that Haidt’s essay helps to engage exactly that kind of liberating curiosity. What sometimes appears to be a dead-end today may become a hopeful way forward if our curiosity can enable us to do something about it.

This post was adapted from my May 8, 2022 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes (but not always) I post the content from one of them here. You can subscribe and not miss any of them by leaving your email address in the column to the right.