Values grounded in religion are moving into the workplace.

What might have been commonplace a hundred years ago for a church-going public became increasingly uncommon over the past 50 years as fewer people identified as believers and the Supreme Court circumscribed the role that religion had once played in public life. Among other things, that meant that most workplaces became religion-free.

At the same time, the American worker was introduced to so-called “corporate values.” As religious values had before them, the hope was that corporate values would provide commitments that the entire workforce could rally around to realize the company’s objectives. In my experience, corporate values have largely failed to either unite or motivate most employees—which is one reason why companies are reaching for deeper, and more explicitly religious hooks to drive that kind of unity and engagement today.

Another reason is the increasing alignment of “political values” with “religious values.” You’ll recall that discussion here a few weeks back, and it didn’t take long to discover how this development was manifesting itself at a local company.

The underlying business insight—that corporate values have proven shallow and largely meaningless—can’t be denied, but dressing work-oriented values in religious garb seems misguided for any company that ties its success to a workforce with diverse talents and experience. Since every company should be aiming for this kind of workforce diversity, employers should be creating work environments where the value priorities that its employees bring to work as opposed to the business owner’s religious values can be advanced.

Before elaborating, some context about the larger forces that are at play here might be helpful.

An Historical Perspective

Cyclical developments that play out over extended time periods can often help to explain what’s happening now.

Last week’s newsletter was about how change agents at work can take hope as well as practical advice from prior historical events when turbulence (like economic recession) permitted the reappraisal or outright rejection of basic assumptions in the workplace. Organized religion also tends to react to moral decline in predictable ways when viewed from history’s perspective. During times when the public seems to have abandoned its moral foundations, religious forces have always seemed to rise up to re-establish them in the workplace and elsewhere.

For the past 400 years, America has witnessed periodic social movements that were aimed at bringing those who had strayed into “sinfulness” back towards “godliness,” or at least “more upstanding” ways of living and working. Moral decline followed by moral revival is part of who we are.

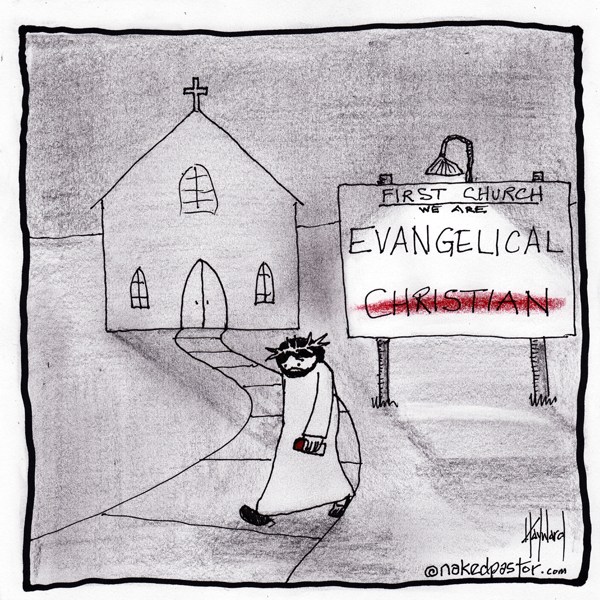

Some of these movements—like the First (1720-60) and Second (1800-1850) Great Awakenings—spanned decades and altered the public’s perceptions of “right and wrong” before the American Revolution and Civil War. More recently, Evangelical Christianity and its political acitvism have been fighting to restore our moral foundations today. In other words, from an historical perspective it’s almost inevitable that concerns about our moral fitness would eventually find their way back into the workplace.

Religious Values Where We Work

The local news article this week was called “Putting Faith at the Forefront: Burlco’s Productive Plastics Brings Corporate Ministry to Work.” Burlco is Burlington County, New Jersey and Productive Plastics is the company’s name.

Just inside the entrance to the workroom at Productive Plastics Inc., which molds plastic into parts for manufacturing companies, is a place to post prayers.

A sign above the section reads, “Welcome to Our Prayer Wall,” in English, Spanish, and Vietnamese, and a notepad and pen hang at the bottom of the space. Tucked into the wall are folded pieces of paper, each left by an employee and containing prayers offered up anonymously.

The company’s goal is an audacious one: To encourage all members of Productive Plastics to pray together for each other.

The prayer wall was discussed at Productive Plastic’s monthly “Caring Team” meeting earlier this month when managers, employees and two “corporate ministers” gathered to share ideas about employee well-being and “ways in which the company can better reflect its core values.

The company is privately held. It’s also “an openly Christian business,” so new employees know its owner’s commitments before signing on to work there. John Zerillo, Productive Plastics vice president of sales describes the company’s focus on its workers as follows: “We’re not there to proselytize. We’re there to care for the needs of the people.” By addressing these needs, Zerillo says the company is no longer losing employees “like we used to.”

The company’s CEO, Hal Gilham, initiated the change. After overcoming some personal challenges, Gilham regretted that he couldn’t extend his faith into his work life. He joined the Philadelphia chapter of C12, a network of Christian CEOs, business owners and executives and made the decision “to extend his born-again Christian values to the way he runs Productive Plastics.”

Beyond the annonymous prayer wall and prayers that employees voluntarily share with one another, each work shift starts with a “Take 5 Meeting.” The first 4 minutes are mandatory where meeting leaders share company notices and manufacturing priorities. The last minute—a short Biblical passage to keep in mind for the day—is optional. Outside its facility, Productive Plastics flies a Christian flag below the American flag. Its four “core company values” lead off with “honor God in all that we do,” followed by develop people, a relentless pursuit of excellence and the need to grow profitability.

Apparently by way of the C12 organization, the company has also hired Lifeguide, a “corporate chaplaincy service” started by Paul and Amy Shumski after years of doing traditional pastoral work. Lifeguide chaplains are available to employees at Productive Plastics who are experiencing work and life problems that affect their jobs and want someone to discuss them with on a confidential basis. Lifeguide charges companies that hire them around $5 per week per employee. According to Paul Shumski’s video presentation at C12, Lifeguide was already working with 7 companies in the greater Philadelphia area by 2017. When interviewed by the newspaper, Amy Shumski said Lifeguard “respects all beliefs” and tries to give employees “skills to help [them] handle their situations” rather than solve their problems for them. The article also indicated that there are at least two non-Christian employees in the company’s workforce.

In digging below the story, one question I had was whether these corporate chaplains also see themselves as missionaries seeking converts to their Evangelical Christianity.

My research couldn’t locate a website for Lifeguide and their ministry referrals may come through the C12 network. Dave Shoemaker, who runs the C12 branch in Philadelphia, introduced Paul Shumski’s corporate chaplaincy presentation in 2017 by saying:

70% of employees do not darken the door of a church. How are they going to find out about Christ?

In the talk that followed, Shumski indicated that he has had over 1800 conversations about spiritual hope in the workplace over the years, that at least 174 employees looked at religious texts during Lifeguide counseling (some for the first time), and how grateful he was for one employee who had “found Jesus” through his workplace ministry.

C12’s website includes a Vision Statement (“To Change the World by Advancing the Gospel in the Marketplace”), a Doctrine Statement (“Jesus Christ is Lord, the whole Bible is wholly true, God has an eternal plan for each believer’s life, and that plan includes their business”), and a library of resources about Christianity and business that appears to be shared by other local C12 groups nationwide.

Some Thoughts

While writing this newsletter, my research didn’t go deep enough to reach conclusions about either Lifeguide or C12, but the story about the rise of Christian chaplaincies in American workplaces did highlight the problem that led me to write my book. Moreover, C12’s and Lifeguide’s approach also differs markedly from the solution I’m proposing.

The Sixties in America challenged traditional authority of every kind. Among other things, mainstream churches lost millions of believers, the objective “truths” of science and social science swamped the more subjective “truths” of religion and the other humanities in colleges and universities, and, for many Americans, values that had been shaped by worshipping communities were replaced by individual perspectives on what is “good” and “bad,” that is, when people bothered to build new moral frameworks at all.

When moral perspectives get watered down or are abandoned altogether—and people become increasingly shallow, materialistic, selfish and self-absorbed— religious revivals like America’s Great Awakenings periodically jump into the void, seeking to restore the nation’s moral compass. The overlapping of Christian Evangelical values with conservative political values is today’s version of this moral revival. It aims to restore the traditional Christian values that many Americans rejected during the Sixties and to give our lives and work a sense of meaning and purpose that they currently lack.

When I started writing WorkLifeReward, I was also concerned that we had torn down the traditional value frameworks and not replaced them with new ones. For many people, morality became increasingly personal and self-contained—private spirituality with little or no public face. Other people seemed to lack direction in life altogether. I was interested in a moral framework that included work because work is about improving more than ourselves. It reflects commitments to others and, more generally, to the world—my internal well-being as well as what I do beyond my selfish concerns.

I was convinced that it would be impossible to “turn back the clock” and restore religious groundings for those who had left them behind. But at the same time, I wanted to identify basic imperatives that would be compatible with traditional beliefs for those who continued to hold them. I also feared the practical consequences of alienating people who could never accept a religious value system; it would exclude too many people who should have the opportunity for a committed and meaningful life but didn’t know how to realize that opportunity. In other words, even if the Lifeguide chaplains aren’t missionaries, they begin their outreach from a moral framework that too many Americans have already rejected as a point of departure when seeking to live their values through their work.

So I took a different approach. I proposed two basic priorities–for personal autonomy and generosity–that can be actively nurtured by non-religious as well as religious people in every kind of work that they do. Moreover a foundation that’s based on these personal values might be able to do a more comprehensive job of filling the moral void that exists today.

My argument—greatly stripped-down here–is that all people at work want to develop and grow in ways that they need to (in terms of competence, collaboration, and aspiration) along with realizing goals that are important to them personally (from bringing well-made products to consumers to improving their community or even the world in some way). This is the value of autonomy that every employee brings to work. Generosity is simply the complementary commitment to acknowledge and support the same drive towards autonomy in others.

These commitments are durable enough to provide the personal meaning and sense of purpose that is lacking today. We don’t “find” these values in the workplace. Instead, we bring these commitments with us when we go to work, hoping to nurture them there as well as in every other part of our lives.

In the same way that it is difficult to be a person who lives (and works) their faith, it takes effort to live (and work) the values of autonomy and generosity. A commitment to individual and collective flourishing is compatible with all traditional religious values, and drives similar levels of motivation and engagement. The first two “corporate values” in every company should be to support their employees’ autonomy and generosity (instead of their boss’s version of them). And when employees don’t experience a commitment to these basic values where they work, they should bring their energy and talent to a workplace that will support them.

Even in America, the revival of moral foundations doesn’t have to be religious in nature.

Note: this post is adapted from my August 19, 2018 weekly newsletter.

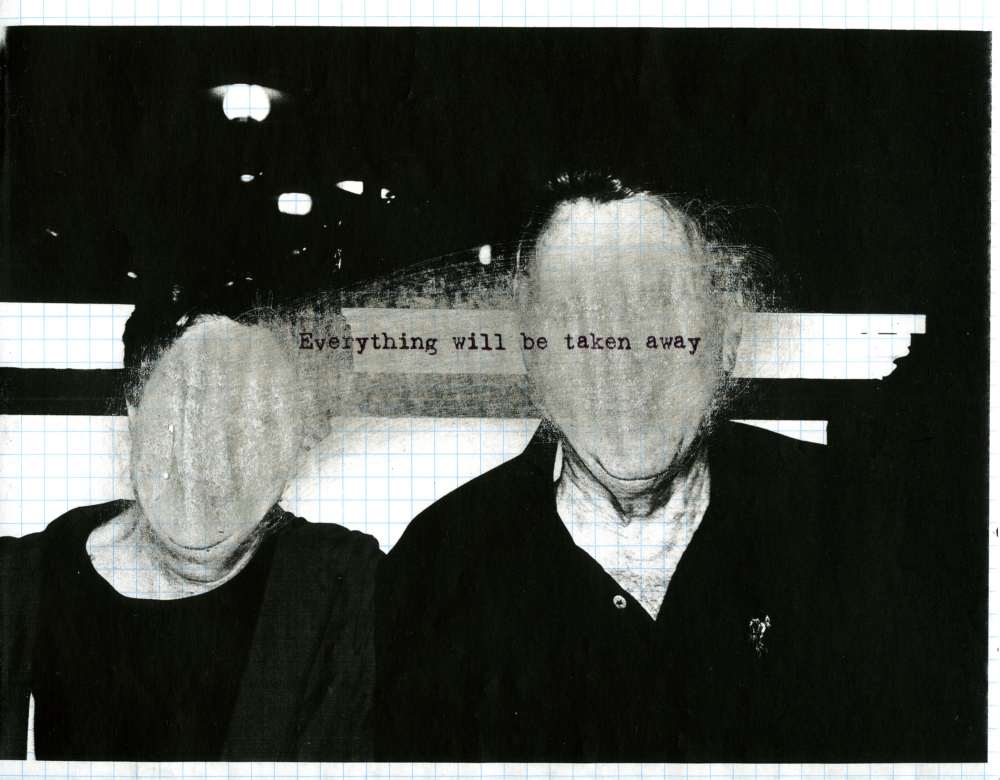

Adrian Piper is a white-looking black woman. Not surprisingly, race and gender have been two of her lifelong preoccupations, but that doesn’t mean she falls into a presumed political category. Instead Piper seems to know more about “our fishbowl” because essential parts of her have spent so much time outside of it. As a result, she’s ended up approaching nearly everything “her way.”

Adrian Piper is a white-looking black woman. Not surprisingly, race and gender have been two of her lifelong preoccupations, but that doesn’t mean she falls into a presumed political category. Instead Piper seems to know more about “our fishbowl” because essential parts of her have spent so much time outside of it. As a result, she’s ended up approaching nearly everything “her way.” Piper went to art school in New York City at the end of the 1960’s. Over the next ten years her texts, videos and performance art aimed at challenging viewers and readers to take a clear-eyed stand for themselves. For example, she often used her own body as a primary image for unannounced public performances, such as walking City streets soaked with wet paint or wearing an Afro wig, fake mustache and mirrored sunglasses to confront people with the stereotype of a young aggressive black male whom she called the Mythic Being. During this time, Piper also got her doctorate in philosophy from Harvard. She has been producing works of art and philosophy ever since.

Piper went to art school in New York City at the end of the 1960’s. Over the next ten years her texts, videos and performance art aimed at challenging viewers and readers to take a clear-eyed stand for themselves. For example, she often used her own body as a primary image for unannounced public performances, such as walking City streets soaked with wet paint or wearing an Afro wig, fake mustache and mirrored sunglasses to confront people with the stereotype of a young aggressive black male whom she called the Mythic Being. During this time, Piper also got her doctorate in philosophy from Harvard. She has been producing works of art and philosophy ever since.