When people decide what is most important to them—and bother to champion it in conversation, in voting, in how they act everyday—they are helping to build the future.

It’s not just making noise, but that’s part of it. For years, when Emily was in grade school, the argument for an all-girl education was that the boys dominated the classroom with their antics and opinions while the girls were ignored or drowned out. Those making the most noise hog the attention, at least at first.

Later on, it’s about the quality of your opinions and the actions that back them up. Power and money in the commons of public life is not synonymous with good commitments or actions, but it does purchase a position with facts and experts and a platform to share it that can hold its own (if not prevail) in the wider debate over what the future will be like and what its trade-offs will cost. Not unlike the over-powered girls in grade school, it takes courage to stand up against what the best-organized, best-financed and most dominant corporate players want.

Part of the problem with these companies today is that many of them are nurturing, so that they can also cater to, lower-level priorities that we all have. For example, we all want convenience in our daily lives and to embrace a certain amount of distraction. The future that some companies want to deliver to us aims at catering to these (as opposed to other) priorities in the most efficient and profitable manner. For example:

-companies like Amazon profit by providing all the convenience you could ever want as a shopper, or

-when when your aim is relief from boredom or stress, social media, on-line games and search engines like Google provide wonderlands of distraction to lose yourself in.

Moreover, with the behavioral data these companies are harvesting from you whenever you’re on their platforms, they’ll hook you with even greater conveniences, forms of escapism and more stuff to buy in the future. Their priorities of efficiency and profit almost perfectly dovetail with ours for convenience and distraction.

This convenient and distracted future—along with a human yearning for something more—is captured with dazzling visuals and melancholy humor in Wall-E, a 10-year old movie from Pixar. (It’s worth every minute for a first or second view of a little trash robot named Wall-E’s bid to save the human race from itself.) In its futuristic world, the round-as-donuts humans who have fled the planet they’ve soiled spend their days on a We’ve-Thought-of-Everything cruise ship that’s floating through space. Except, as it turns out, the ship’s operators aren’t providing everything their passengers want and need, or want and need even more, like a thriving planet to call home.

Wall-E’s brilliance doesn’t come from an either/or future, but from a place where more important priorities are gradually acknowledged and acted upon too. It’s deciding to have more of some things and somewhat less of others. Back in the real world, that change in priorities might involve diverting some of our national resources away from economic efficiency and profit to support thriving families and communities (January 27, 2019 newsletter). Or, as in Wall-E’s case, using fewer of our shared resources for convenience and distraction and more for restoring an environment that can sustain our humanity in deeper ways.

On the other hand, as anyone who has tried it knows: it can be hard to find enough courage to stand up to those who are dominating (while they’re also subverting) the entire conversation about what we should want most. It’s our admiration for Wall-E’s kind of courage that makes Toronto’s citizens so inspiring today. Why these northern neighbors? Because they are trying through their actions to meet a primary shared objective—which is to build a sustainable urban environment that protects its natural resources—without losing sight of other priorities like efficiency, convenience and strengthening the bonds of family and community in their city.

And as if that weren’t enough, there is another wrinkle to the boldness that Torontonians are currently demonstrating. The City is partnering with tech giant Google on a key piece of data-driven redevelopment. As we admire them from afar, maybe we can also learn some lessons about how to test-drive a carbon-free future while helping that future to evolve with data we provide as we live and work. This fascinating and hopeful city is raising the kinds of questions that can only be asked when a place has the courage to stop talking about its convictions and start acting on them.

I was walking in lower Manhattan this week when I caught the sign above, encouraging me to bring my hand in for a palm reading.

I knew the fortuneteller wouldn’t find my future there, but she was probably right about one thing. Your prior experience is etched in the lines on your hands and your face. But as to where these lines will take you next, the story that Toronto is writing today is likely to provide better guidance than she will—and more information about the priorities to be weighed and measured along the way.

1. A Carbon-Free Future

Toronto has initiated two experiments, one is to gradually reduce its carbon footprint to nothing and the other is to build a community from the ground up with the help of data from its new residents. Both experiments are in the early stages, but they provide tantalizing glimpses into the places where we all might be living and working if we commit to the same priorities as Toronto.

When I’ve visited this City, it always seemed futuristic to me but not because of its built environment. Instead, it was its remarkably diverse population drawn in large numbers from every corner of the globe. Only later did I learn that over half of Toronto’s population is foreign-born, giving the place a remarkable sense of optimism and new beginnings.

Declaring its intention to radically reduce its use of fossil fuels, Toronto has taken a long stretch of King Street, one of the City’s busiest commercial and recreational boulevards, and implemented a multi-faceted plan that bans most private traffic, upgrades the existing streetcar system, concentrates new residential and commercial space along its corridor, and utilizes these densities and proximities to encourage both walking and public transportation for work, school, shopping and play.

In contrast to a suburban sprawl of large homes and distant amenities that require driving, Toronto’s urbanized alternative offers smaller living spaces, more contact with other members of the community, far less fuel consumption, and reclaimed spaces for public use that were once devoted to parking or driving. One hope is that people will feel less isolated and lonely as proximity has them bumping into one another more regularly. Another is that residents and workers visiting daily will become more engaged in public life because they’ll need to cooperate in order to share its more concentrated spaces.

Toronto’s King Street experiment envisions a time when all of its streets will be “pedestrianized.” There will still be cars, but fewer will be in private hands and those that remain will be rented as needed—anticipating the rise of on-call autonomous vehicles. Streets and roads will also remain, but they will increasingly be paid for by those who use them most, further reducing the need for underutilized roadways and freeing up space for other uses like parks and recreational corridors.

Toronto’s experiment in urban living also promotes a “sharing economy,” with prices for nearly everything reduced when the cost is shared with others. Academics like Daniel Hoornweg at the University of Ontario’s Institute of Technology have been particularly interested in using reduced prices to drive the necessary changes. It’s “sharing rides, sharing tools, sharing somebody to look after your dog when you’re not there,” says Hoornweg. Eventually, the sharing economy that started with Uber and Airbnb will become almost second nature as it becomes more affordable and residents exchange their needs to own big homes and cars for other priorities like a sustainable environment, greater access to nature within an urban area, and more engagement over shared pursuits with their neighbors.

For a spirited discussion about Toronto’s King Street experiment that includes some of its strongest boosters, you can listen here to an NPR-Morning Edition segment that was broadcast earlier this week.

2. Toronto’s Quayside Re-Development

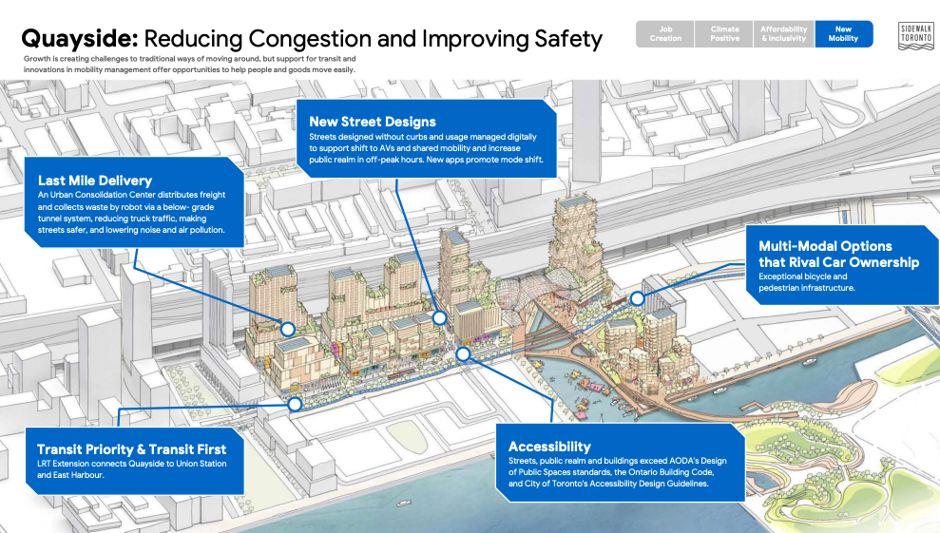

Much like in Philadelphia where I’m writing this post, some of Toronto’s most desireable waterfront areas have been isolated from the rest of its urban center by a multi-lane highway. In response, Toronto has set aside a particularly lifeless area “of rock-strewn parking lots and heaps of construction materials” that’s spread over a dozen acres for the development of another urban experiment, this time in partnership with a “smart-cities” Google affiliate called Sidewalk Labs. In October, a coalition of the City, Ontario and Canadian governments contracted with Sidewalk to produce a $50 million design for a part of town that’s been renamed Quayside, or what Sidewalk calls “the world’s first neighborhood built from the internet up”—a sensor-enabled, highly wired environment that promises to run itself.

According to a recent article in Politico (that you can also listen to), Quayside will be “a feedback-rich” smart city “whose constant data flow [will] let it optimize services constantly” because it is “not only woven through with sensors and Wi-Fi, but [also] shaped around waves of innovation still to come, like self-driving cars.” For example, in keeping with Toronto’s other pay-as-you-go priorities, one of Quayside’s features will be “pay-as-you-throw” garbage chutes that automatically separate out recyclables and charge households for their waste output.

Here are a couple of views of the future development, including tags on some of the promised innovations.

A truly smart city runs on data that is generated from its inhabitants and behaviorally informed algorithms instead of on decisions that are made by Sidewalk’s managers or public officials. Not surprisingly, this raises a series of legal and quality of life questions.

On the legal side, those questions include: who owns the data produced by Sidewalk’s sensors and WiFi monitors; who controls the use of that data after it’s been generated; and whose laws apply when conflicts arise? On the issue of data privacy (and other potential legal differences), the Politico article notes that there are:

few better places to have this conversation than Canada, a Western democracy that takes seriously debates over informational privacy and data ownership—and is known for managing to stay polite while discussing even hot-button civic issues.

Moreover, because Canadians view personal privacy as a fundamental human right instead of one that can be readily traded for a “free” Gmail account or access to Google’s search engine, Sidewalk has already stipulated that data collected in Quayside will never be used to sell targeted advertising.

Undesirable human impacts from machine decision-making have also been raised, and Sidewalk is hoping to minimize these impacts by asking the City’s residents in advance for their own visions and concerns about Quayside. A year of consultations is already informing the initial plan.

Longer term, urbanists like Arielle Arieff worry about “the gap between what data can and cannot do” when running a neighborhood. Part of the beauty of city living is the connections that develop “organically”–chance occurrences and random encounters that a database would never anticipate. Arieff says: “They really do believe in their heart and soul that it’s all algorithmically controllable, but it’s not.” As if to confirm her suspicions, Sidewalk’s lead manager seems equally convinced that today’s technology can “optimize everyone’s needs in a more rational way.”

Given the expertise and perspective Toronto will be gaining from its King Street experiment and its citizens’ sensitivity to human concerns (like privacy) over efficiency concerns (like convenience), there is room for optimism that the City will strike a livable balance with its high tech partner. Moreover, Sidewalk Labs has a significant incentive to get it right in Quayside. There is an adjacent and currently available 800-acre lot known as Port Lands, “a swath of problem space big enough to become home to a dozen new neighborhoods in a growing metropolis.”

To me, Toronto’s Quayside experiment seems to have little downside, with more serious issues arising in Sidewalk’s future smart city projects. Sidewalk may not be selling its Toronto data to advertisers, but it will be vastly more knowledgeable than other cities that lack either the rich pools of behavioral data it has accumulated in Toronto or the in-house expertise to interpret it. Among other things, this creates a power imbalance between a well-funded private contractor and underfunded cities that lack the knowledge to understand what they stand to gain or to forge a working partnership they can actually benefit from. Simone Brody, who runs the Bloomberg Philanthropies’ “What Works Cities” project, says: “When it comes to future negotiations, its frightening that Google will have the data and [other] cities won’t.”

But these are longer-range concerns, and there is reason today for cautious optimism that American regulators (for example) will eventually begin to treat powerful tech companies that are amassing and utilizing public data more like “utilities” that must serve the public as well as their own profit-driven interests. That kind of intervention could help to level the public-private playing field, but it’s also a discussion for another day.

In the meantime, Toronto’s boldness in experimenting its way to a future that champions its priorities through the latest innovations is truly inspiring. The cities and towns where the rest of us live and work have much to learn from Toronto’s willingness to claim the future it wants by the seat of its pants.

This post was adapted from my March 17, 2019 newsletter.