More than usual, I faced a blank screen when I sat down to write yesterday.

On the usual Saturday, I have an outline in my head, some sources down, and a bead on a compatible image or two.

Maybe, probably, it was the holiday, since I still haven’t completed everything I usually do on this day, like ruminating on those things I’m most grateful for in the past year.

When I came upon a recent list amidst the recipes, I had to laugh when I saw that I’d made note of this one: the occasional accuracy of my intuitions. Because when you put your wiriting out there, you can never even begin without some measure of confidence.

Which brings me to the related topic I landed upon today: How I decided what to write to you?

Some of it comes from the choices made by others.

Even though I’m reading fewer books, I still pour over the year-end booklists—for this reason of course, and also (I suppose) to feel guilty about not reading more tomes and chronicles that sound essential or fascinating.

As luck would have it, the “NYT’s 100 Notable Books for 2025,” “WSJ’s 2025 Guide to Holiday Gift Books,” and “The Economist’s Best Books of 2025” brought me to short reviews about John Updike’s 1989 memoir “Self Consciousness” and Susan Orlean’s 2025 memoir “Joyride.” (I ordered both “for the pile,” so my guilt can be closer at hand.)

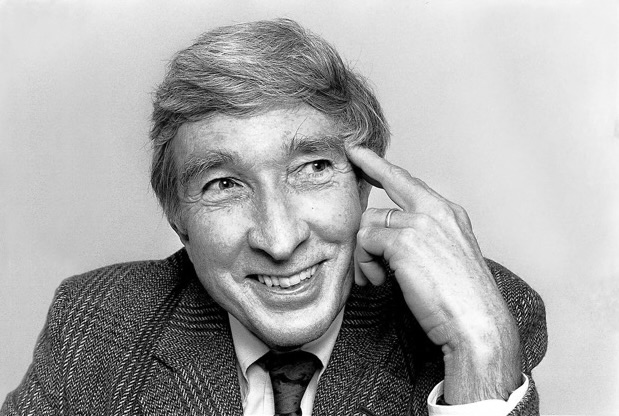

Of couse, Updike was one of America’s pre-eminent writers during much of my lifetime. I read, but didn’t get, “Rabbit Run” in high school, part of his series of droll & insightful takes on suburban life & love. As I started living what he’d written about, I grew to appreciate his Rabbit & other novels, but even more to value the economy of his wisdom when he’d pen an essay someplace or get candid in an interview and then proceed to bowl me over.

(That’s Updike, over-coming his bad teeth, psoriasis & ever-present shyness in the picture above.)

So I was overtaken again when I came upon the following about (essentially) where he begins as a writer, describing his childhood sense “of an embowering wide world arranged for my mystification and entertainment.”

His subject matter was set out for him like a buffet, in all its “embowering” (or “embracing,” in the way that trees would) possibility, with his job to make what he could of it all, a kind of bird’s eye view one minute, more closely-observed the next, but all there for his “mystification and entertainment”—and eventually ours.

If I were so inclined (in other words), all I had to do was look at the world around me and see what’s tickling my fancy.

Author Susan Orlean in the middle of one of her buffets.

Since I already knew Orlean’s “The Orchid Thief” and the non-fiction essays in the New Yorker that spawned both it and other absorbing romps, I quickly zeroed in on the review of “Joyride,” because that’s exactly what her job as a writer always felt like to me whenever she invited me along

Orlean, like Updike, confesses that she too “believe[s] the world has something to tell [her],” and her amazement at what she heard is one of the qualities that makes her writing so infectious.

For example, “The Orchid Thief” is broadly about her reporting of the 1994 arrest of an horticulturist and members of the Seminole nation for poaching rare orchids in the Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve in South Florida. But beyond its colorful cast & humorous asides, it is also brought Orlean, for the first time, face-to-face with true obsession, in this instance, that horticulturist’s quest to find & clone the rare ghost orchid for profit.

Demonstrating how she finds what to write about, her memoir reveals that she happened upon the seeds that became “The Orchid Thief” on an airplane, where a day-old copy of the Miami Herald had been left in her seat pocket. Buried inside was a story about an upcoming trial over some valuable plants. Within days, Orlean was in Miami, at the courthouse.

While she acknowledges that she’s always been open to the thrill of discoveries like this in her story-telling, Orlean acknowledges that there’s also a different kind of writer, namely, “those who have something they want to say to the world.” In other words, it’s not the world as your oyster (waiting for you to discover its delights or ponder its mysteries), but about some internal fire that drives this different breed of writer to tell the world what’s on her (or his) mind..

One or the other of these propensities tends to announce itself early in writers (Updike’s “childhood sense”), and likely in non-writers too. For example, I’m currently working with a physical therapist who’s so in love with the next Broadway musical, golf game or Top 10 list of horror movies that I quickly got him to admit that he’s always (“since I was a little kid”) been open to the delights his slice of the world kept offering up to him. Even more importantly, his pursuit of the next delight always seems to drive him to prescribe whatever will make David better.

As a writer, and before that, as a child, I always had that other kind of perspective, wanting to say something to the world before I ever realized that it might be listening. It was odd, because I’m hardly an extravert. But once “whatever it was” was done percolating, it always had to come out someplace, overcoming any inhibitions or stage fright that might stand in its way.

You’ve probably noticed that many of these posts are driven by that impulse. It’s why when Kyla Scanlon wrote about how a prosperous future no longer seems evident in the broken world that we see and experience every day, I wanted to shout out, “Yes, I agree with you, Kyla!” Since we’re supposedly so rich, I want my streets to be cleaner $ safer, my neighbors to be less anxious & more confident about the future instead of charting America’s prosperity in the cold comfort of data centers, AI chips & invisible wealth, as I wrote on this page last week (“Our Future Will Only Be Better When We Change It.””)

It’s why I wrote about Trump here for several weeks until I convinced myself that he’s effectively done, that are wobbly institutions are still likely to prove resilient enough to blunt his most serious damage. I also kept writing about him because I wanted at least some of you to know that you’re not alone in your alarm at seeing his unprecedented misuse of our nation’s highest office, and (I’m sure) as a kind of reassurance that we (in Susan Sontag’s words) “are not accomplices” to the damage he’s causing, even though we are witnesses to it & citizens with stakes in our governance. In all these regards, Trump is lighting fewer internal fires that I need to vent about.

Yet while many of my posts are still driven by the desire to tell the world something (or to trumpet some other writer who’s doing so), I’ve also learned that I can get tired of hearing my mountain-top voice, and at such times, I try to see the world as my oyster too, like I did recently in my journey to a local gas station framed by reflections of its spiritual past (“Is the Solution a Speed Bump?’), in this summer’s Short Stack posts (here, here and here), and when I escape into the smorgasbords of art, TV & music.

At such times, I’m both surprised & relieved by this bit of counter-programming. It’s like surfer and art critic Dave Hickey wrote in “The Perfect Wave” (another worthwhile read):

When[ever] something that is not your thing blows you away, that’s one of the best things that can happen. It means you are something other than you thought you were.

It always feels like a revelation. New doors seem to open when I’ve nothing left to say.

This post was adapted from my November 30, 2025 newsletter. Newsletters are delivered to subscribers’ in-boxes every Sunday morning, and sometimes I post the content from one of them here, in lightly edited form. You can subscribe by leaving your email address in the column to the right.