The norms that dictate the acceptable use of artificial intelligence in technology are in flux. That’s partly because the AI-enabled, personal data gathering by companies like Google, Facebook and Amazon has caused a spirited debate about the right of privacy that individuals have over their personal information. With your “behavioral” data, the tech giants can target you with specific products, influence your political views, manipulate you into spending more time on their platforms, and weaken the control that you have over your own decision-making.

In most of the debate about the harms of these platforms thus far, our privacy rights have been poorly understood. In fact, our anything-but-clear commitments to the integrity of our personal information have enabled these tech giants to overwhelm our initial, instinctive caution as they seduced us into believing that “free” searches, social networks or next day deliveries might be worth giving them our personal data in return. Moreover, what alternatives did we have to the exchange they were offering?

- Where were the privacy-protecting search engines, social networks and on-line shopping hubs?

- Moreover, once we got hooked on to these data-sucking platforms, wasn’t it already too late to “put the ketchup back in the bottle” where our private information was concerned? Don’t these companies (and the data brokers that enrich them) already have everything that they need to know about us?

Overwhelmed by the draw of “free” services from these tech giants, we never bothered to define the scope of the privacy rights that we relinquished when we accepted their “terms of service.” Now, several years into this brave new world of surveillance and manipulation, many feel that it’s already too late to do anything, and even if it weren’t, we are hardly willing to relinquish the advantages of these platforms when they are unavailable elsewhere.

So is there really “no way out”?

A rising crescendo of voices is gradually finding a way, and they are coming at it from several different directions.

In places like Toronto (London, Helsinki, Chicago and Barcelona) policy makers and citizens alike are defining the norms around personal data privacy at the same time that they’re grappling with the potential fallout of similar data-tracking, analyzing and decision-making technologies in smart-city initiatives.

Our first stop today is to eavesdrop on how these cities are grappling with both the advantages and harms of smart-city technologies, and how we’re all learning—from the host of scenarios they’re considering—why it makes sense to shield our personal data from those who seek to profit from it. The rising debate around smart-city initiatives is giving us new perspectives on how surveillance-based technologies are likely to impact our daily lives and work. As the risks to our privacy are played out in new, easy-to-imagine contexts, more of us will become more willing to protect our personal information from those who could turn it against us in the future.

How and why norms change (and even explode) during civic conversations like this is a topic that Cass Sunstein explores in his new book How Change Happens. Sunstein considers the personal impacts when norms involving issues like data privacy are in flux, and the role that understanding other people’s priorities always seems to play. Some of his conclusions are also discussed below. As “dataveillance” is increasingly challenged and we contextualize our privacy interests even further, the smart-city debate is likely to usher in a more durable norm regarding data privacy while, at the same time, allowing us to realize the benefits of AI-driven technologies that can improve urban efficiency, convenience and quality of life.

With the growing certainty that our personal privacy rights are worth protecting, it is perhaps no coincidence that there are new companies on the horizon that promise to provide access to the on-line services we’ve come to expect without our having to pay an unacceptable price for them. Next week, I’ll be sharing perhaps the most promising of these new business models with you as we begin to imagine a future that safeguards instead of exploits our personal information.

1. Smart-City Debates Are Telling Us Why Our Personal Data Needs Protecting

Over the past 6 months, I’ve talked repeatedly about smart-city technologies and one of you reached out to me this week wondering: “What (exactly) are these new “technologies”?” (Thanks for your question, George!).

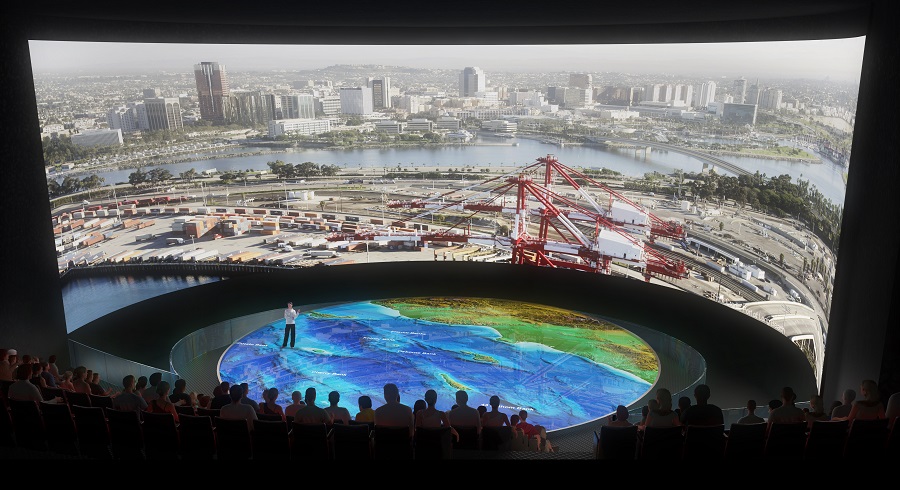

As a general matter, smart-city technologies gather and analyze information about how a city functions, while improving urban decision-making around that new information. Throughout, these data-gathering, analyzing, and decision-making processes rely on artificial intelligence. In his recent article “What Would It Take to Help Cities Innovate Responsibly With AI?” Eddie Copeland begins by describing the many useful things that AI enables us to do in this context:

AI can codify [a] best practice and roll it out at scale, remove human bias, enable evidence-based decision making in the field, spot patterns that humans can’t see, optimise systems too complex for humans to model, quickly digest and interpret vast quantities of data and automate demanding cognitive activities.

In other words, in a broad range of urban contexts, a smart-city system with AI capabilities can make progressively better decisions about nearly every aspect of a city’s operations by gaining an increasingly refined understanding of how its citizens use the city and are, in turn, served by its managers.

Of course, the potential benefits of greater or more equitable access to city services as well as their optimized delivery are enormous. Despite some of the current hew and cry, a smart-cities future does not have to resemble Big Brother. Instead, it could liberate time and money that’s currently being wasted, permitting their reinvestment into areas that produce a wider variety of benefits to citizens at every level of government.

Over the past weeks and months, I’ve been extolling the optimism that drove Toronto to launch its smart-cities initiative called Quayside and how its debate has entered a stormy patch more recently. Amidst the finger pointing among Google affiliate Sidewalk Labs, government leaders and civil rights advocates, Sidewalk (which is providing the AI-driven tech interface) has consistently stated that no citizen-specific data it collects will be sold, but the devil (as they say) remains in the as-yet to be disclosed details. This is from a statement the company issued in April:

Sidewalk Labs is strongly committed to the protection and privacy of urban data. In fact, we’ve been clear in our belief that decisions about the collection and use of urban data should be up to an independent data trust, which we are proposing for the Quayside project. This organization would be run by an independent third party in partnership with the government and ensure urban data is only used in ways that benefit the community, protect privacy, and spur innovation and investment. This independent body would have full oversight over Quayside. Sidewalk Labs fully supports a robust and healthy discussion regarding privacy, data ownership, and governance. But this debate must be rooted in fact, not fiction and fear-mongering.

As a result of experiences like Toronto’s (and many others, where a new technology is introduced to unsuspecting users), I argued in last week’s post for longer “public ventilation periods” to understand the risks as well as rewards before potentially transformative products are launched and actually used by the public.

In the meantime, other cities have also been engaging their citizens in just this kind of information-sharing and debate. Last week, a piece in the New York Times elaborated on citizen-oriented initiatives in Chicago and Barcelona after noting that:

[t]he way to create cities that everyone can traverse without fear of surveillance and exploitation is to democratize the development and control of smart city technology.

While Chicago was developing a project to install hundreds of sensors throughout the city to track air quality, traffic and temperature, it also held public meetings and released policy drafts to promote a City-wide discussion on how to protect personal privacy. According to the Times, this exchange shaped policies that reduced, among other things, the amount of footage that monitoring cameras retained. For its part, Barcelona has modified its municipal procurement contracts with smart cities technology vendors to announce its intentions up front about the public’s ownership and control of personal data.

Earlier this year, London and Helsinki announced a collaboration that would enable them to share “best practices and expertise” as they develop their own smart-city systems. A statement by one driver of this collaboration, Smart London, provides the rationale for a robust public exchange:

The successful application of AI in cities relies on the confidence of the citizens it serves.

Decisions made by city governments will often be weightier than those in the consumer sphere, and the consequences of those decisions will often have a deep impact on citizens’ lives.

Fundamentally, cities operate under a democratic mandate, so the use of technology in public services should operate under the same principles of accountability, transparency and citizens’ rights and safety — just as in other work we do.

To create “an ethical framework for public servants and [a] line-of-sight for the city leaders,” Smart London proposed that citizens, subject matter experts, and civic leaders should all ask and vigorously debate the answers to the following 10 questions:

- Objective– why is the AI needed and what outcomes is it intended to enable?

- Use– in what processes and circumstances is the AI appropriate to be used?

- Impacts– what impacts, good and bad, could the use of AI have on people?

- Assumptions– what assumptions is the AI based on, and what are their iterations and potential biases?

- Data– what data is/was the AI trained on and what are their iterations and potential biases?

- Inputs– what new data does the AI use when making decisions?

- Mitigation– what actions have been taken to regulate the negative impacts that could result from the AI’s limitations and potential biases?

- Ethics– what assessment has been made of the ethics of using this AI? In other words, does the AI serve important, citizen-driven needs as we currently understand those priorities?

- Oversight– what human judgment is needed before acting on the AI’s output and who is responsible for ensuring its proper use?

- Evaluation– how and by what criteria will the effectiveness of the AI in this smart-city system be assessed and by whom?

As stakeholders debate these questions and answers, smart-city technologies with broad-based support will be implemented while citizens gain a greater appreciation of the privacy boundaries they are protecting.

Eddie Copeland, who described the advantages of smart-city technology above, also urges that steps beyond a city-wide Q&A be undertaken to increase the awareness of what’s at stake and enlist the public’s engagement in the monitoring of these systems. He argues that democratic methods or processes need to be established to determine whether AI-related approaches are likely to solve a specific problem a city faces; that the right people need to be assembled and involved in the decision-making regarding all smart-city systems; and that this group needs to develop and apply new skills, attitudes and mind-sets to ensure that these technologies maintain their citizen-oriented focus.

As I argued last week, the initial ventilation process takes a long, hard time. Moreover, it is difficult (and maybe impossible) to conduct if negotiations with the technology vendor are on-going or that vendor is “on the clock.”

Democracy should have the space and time to be a proactive instead of reactive whenever transformational tech-driven opportunities are presented to the public.

2. A Community’s Conversation Helps Norms to Evolve, One Citizen at a Time

I started this post with the observation that many (if not most) of us initially felt that it was acceptable to trade access to our personal data if the companies that wanted it were providing platforms that offered new kinds of enjoyment or convenience. Many still think it’s an acceptable trade. But over the past several years, as privacy advocates have become more vocal, leading jurisdictions have begun to enact data-privacy laws, and Facebook has been criticized for enabling Russian interference in the 2016 election and the genocide in Myanmar, how we view this trade-off has begun to change.

In a chapter of his new book How Change Happens, legal scholar Cass Sunstein argues that these kinds of widely-seen developments:

can have a crucial and even transformative signaling effect, offering people information about what others think. If people hear the signal, norms may shift, because people are influenced by what they think other people think.

Sunstein describes what happens next as an “unleashing” process where people who never formed a full-blown preference on an issue like “personal data privacy (or were simply reluctant to express it because the trade-offs for “free” platforms seemed acceptable to everybody else), now become more comfortable giving voice to their original qualms. In support, he cites a remarkable study about how a norm that gave Saudi Arabian husbands decision-making power over their wives’ work-lives suddenly began to change when actual preferences became more widely known.

In that country, there remains a custom of “guardianship,” by which husbands are allowed to have the final word on whether their wives work outside the home. The overwhelming majority of young married men are privately in favor of female labor force participation. But those men are profoundly mistaken about the social norm; they think that other, similar men do not want women to join the labor force. When researchers randomly corrected those young men’s beliefs about what other young men believed, they became far more willing to let their wives work. The result was a significant impact on what women actually did. A full four months after the intervention, the wives of men in the experiment were more likely to have applied and interviewed for a job.

When more people either speak up about their preferences or are told that others’ inclinations are similar to theirs, the prevailing norm begins to change.

A robust, democratic process that debates the advantages and risks of AI-driven, smart city technologies will likely have the same change-inducing effect. The prevailing norm that finds it acceptable to exchange our behavioral data for “free” tech platforms will no longer be as acceptable as it once was. The more we ask the right questions about smart-city technologies and the longer we grapple as communities with the acceptable answers, the faster the prevailing norm governing personal data privacy will evolve.

Our good work of citizens is to become more knowledgeable about the issues and to champion what is important to us in dialogue with the people who live and work along side of us. More grounds for protecting our personal information are coming out of the smart-cities debate and we are already deciding where new privacy lines should be drawn around us.

This post was adapted from my July 7, 2019 newsletter. When you subscribe, a new newsletter/post will be delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning.