I saw rooms full of models of imagined buildings and cities at the Museum of Modern Art in New York this week. The artist was Bodys Isek Kingelez from central Africa. Pictured above is one of his futuristic building models. They reflect “dreams for his country,” known during his life as the Belgian Congo and later as Zaire. Kingelez said he was envisioning “a more harmonious society” than he saw around him.

Artists are sometimes better at envisioning than the rest of us. It can be even harder for us to bring a better future into our day-to-day work—but when we do, our hopes pull us forward, particularly as we struggle to realize them.

Acting on what we hope for is one of good work’s foundations. So are acting out of our aim for both generosity and autonomy on the job. I’ve been thinking about demonstrations of generosity, autonomy and acting on hope this week from teacher/writer Roxanne Gay, actor/rap artist/omnivore Riz Ahmed, and activist/public intellectual Rebecca Solnit, respectively—3 powerful voices with a lot to say about how we spend our time and talent every day.

Generous Judgment

Generosity is about acknowledging the autonomy or self-determination of others (like co-workers, clients/customers, suppliers, members of your business and non-profit communities) in the course of your work.

You probably know comic Louis C.K. Highly acclaimed, his semi-autobiographical cable TV show Louis and stand-up comedy specials have won 6 Emmy awards, a Peabody, and star-struck interviews at places like Fresh Air. To me, his comedy seemed deep, subtle, smart, and self-aware. Until late last year, when he was “outed” by several women who worked with him, it seemed that Louis C.K. could do no wrong. They accused him of pretty egregious conduct that reminded me of apocryphal stories I used to hear about neighborhood “flashers,” only this time much worse, because he was not the sicko stranger in a trench coat. Instead, several in his reluctant audience had tied their careers to his.

As the story came out (on the heels of Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey, Charlie Rose and others), I was surprised by the “not enough” of his public reactions and the suggestions around them that he had previously tried to bully his accusers into silence. Well this week, less than a year after the revelations first surfaced, Louis C.K. returned to a thunderous reaction “on the come-back trail.” The crowd that felt lucky enough to be at a NYC comedy club for his unannounced performance was reportedly ecstatic.

Clearly, Louis C.K. didn’t know how to handle the “world of hurt” around his abusive conduct when it first came out and was similarly clueless when he concluded “that all had been forgotten” and “it is time for everybody to just move on.” In a New York minute, Roxanne Gay told him otherwise.

It might have been easier for Louis if his comeuppance hadn’t been in the New York Times. But she didn’t just excoriate him. She met him like she acknowledged his intelligence, his talent, his fans who might still learn from what she was about to say. Instead of writing him off as a perverted loser, Gay told him what he (along with others who don’t know but need to hear) what should be done by adults who behave this way. It was a gift he may not have deserved, but it was a judgment that was elevated by the light that she brought to it.

“If Louis C.K. doesn’t know what to do when he’s caused this kind of damage, then I’ll try to explain it,” she seems to say—so he can make it right this time, and others like him can learn what they need to do too. Anger followed by patience in that New York minute was an act of generosity. Indeed, it’s a balance that elevates nearly everything that Roxanne Gay does.

While you should read her entire commentary, this is Gay on Louis C.K.’s “comeback road”:

How long should a man like Louis C.K. pay for what he did? At least as long as he worked to silence the women he assaulted and at least as long as he allowed them to doubt themselves and suffer in the wake of his predation and at least as long as the comedy world protected him even though there were very loud whispers about his behavior for decades.

He should pay until he demonstrates some measure of understanding of what he has done wrong and the extent of the harm he has caused. He should attempt to financially compensate his victims for all the work they did not get to do because of his efforts to silence them. He should facilitate their getting the professional opportunities they should have been able to take advantage of all these years. He should finance their mental health care as long as they may need it. He should donate to nonprofit organizations that work with sexual harassment and assault victims. He should publicly admit what he did and why it was wrong without excuses and legalese and deflection. Every perpetrator of sexual harassment and violence should follow suit.

Moral condemnation is easy but describing the “road someone needs to take back” requires a comprehension of the pain that was caused, the actions that would be necessary to alleviate it, as well as the belief that he could act on your advice. Most judgments fail to include these components, but Gay’s has all of them.

The Christian lesson of the crucifixion is infinitely more powerful because it is followed by the resurrection. We’re expert at crucifying people today—at work, and otherwise—but too often seem to be unconcerned about their ability (and ours) to rise afterwards. It’s not about forgiveness but the hard-won path to change.

The last time I wrote about Roxanne Gay on this page was in January.

Creative Autonomy

Autonomy is actively making the most out of what you have, identifying what is important to you, and putting yourself on the line to achieve it. Autonomy is self-determination.

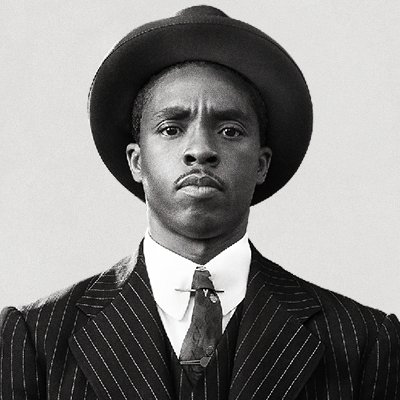

In the limited series The Night Of (on HBO), Riz Ahmed played two roles: the role of a Pakistani student wrongly imprisoned at Riker’s Island for murder and a role beneath his acting that involved you as a viewer in a separate dialogue. You could feel Ahmed’s intelligence, focus and humanity whispering through his role—his interior life giving the 6 episodes counterpoints beyond the writing, directing and acting. (“Whatever he was saying and doing, he was always simultaneously maintaining a second conversation with you about what both of you might be thinking.”)

A profile with that line and additional suggestions about Ahmed’s perspective was this week’s cover story in the New York Times Magazine. You can sense what’s unique about him from the first impressions that Ahmed made on his profiler about his jobs as an actor and musician, pathfinder, role-model and activist.

It’s not that he doesn’t get animated. He does. Talking with Ahmed can be a little like sparring, a little like co-writing a constitution, a little like saving the world in an 11th-hour meeting. He interrupts, then apologizes for interrupting, then interrupts again. He can deliver entirely publishable essays off the top of his head. He pounds the table when talking about global injustices, goes back to edit his sentences minutes after they were spoken, challenges the premises of your sentences before you’re halfway through speaking. This is what happens when you cut your teeth on both prep-school debate teams and late-night freestyle rap battles, as Ahmed has. He is like someone who wants to speak truth to power but now is power — famous enough, at least, to have people listen to his ideas. He is like someone very smart who also cares a lot. He is like someone who doesn’t want to be misunderstood.

Not surprisingly, much of Ahmed’s edge comes from being a Pakistani-Brit, rising from one competitive lower school to another. Along the way, he felt his separateness as a South Asian but always “believed that the flag of Britain should and would obviously include him.” That is, until Al Qaeda’s attack on Twin Towers, which happened the month he matriculated to university and made it even more burdensome to be a Muslim. It was there that he made a critical life choice.

[H]e found himself at Oxford University, just after 9/11 — a brown kid surrounded by the acolytes of seemingly ancient white wealth, who sometimes did have a way of talking to him as if he were a shopkeeper. Rather than retreating into Oxford, he decided to make Oxford come to him. He started organizing parties that celebrated his music and cultural touchstones, parties where he would get on the mic over drum ’n’ bass records. Soon enough, the event he co-founded, “Hit and Run,” moved to Manchester and became one of the city’s leading underground music events.

What could have been angry rejection and a retreat to the company of other South Asian Muslims instead became his invitation for Oxford to join a broader conversation that he was sponsoring. It was a place where he mashed up Pakistani melodies and rhythms with British rap (just as rap was rising to become the most popular music in the world.) As Lena Dunham observed about him, he combined the bravado of someone in the hip-hop world with the intensity of someone who’s mounted a barricade.

Creating this platform was a singular act of personal autonomy (as well as generosity towards others) that has informed Riz Ahmed’s work ever since. He wants to initiate a conversation that’s big enough for him and for everyone else. It’s a theme that shines through every corner of his remarkable story. I hope that you’ll enjoy digging into more of it.

Living Your Vision

Envisioning is living the future that you hope for through your work.

I read Rebecca Solnit’s “Hope in the Dark” traveling to and from New York City. In a nutshell, it’s about living what’s important to you, even though there is no assurance or even likelihood that the better world you’re working for will get any closer as a result. As her title says, it’s hope in the dark.

Americans in particular tend to want more certainty than that. We’re not accustomed to a continuous struggle for a better world or trying to “live our hopes”–particularly when they may never be realized–every day. Instead, we tend to respond to a crisis/problem/challenge, declare victory or defeat, and go home to wait for the next one to demand our attention. Our responses are generally to emergencies that interrupt the normal flow of our lives. We don’t tend to see struggling for what’s important to us as a daily commitment.

Solnit argues that treating struggles for justice, fairness, freedom, for greater opportunity, self-determination or a healthier planet as isolated emergencies results in abandoning our victories while they’re still vulnerable and conceding our defeats too quickly. When we’re committed to achieving what’s truly important to us, Solnit argues: “It is always too soon to go home.”

She illustrates her point by recounting a story she wrote several years back about pay equity for women:

[A] cranky guy wrote in that women used to make sixty-two cents to the male dollar and now we made seventy-seven cents, so what were we complaining about? It doesn’t seem like it should be so complicated to acknowledge that seventy-seven cents is better than sixty-six cents and that seventy-seven cents isn’t good enough, but the politics we have is so pathetically bipolar that we only tell this story two ways: either seventy-seven cents is a victory, and victories are points where you shut up and stop fighting; or seventy-seven cents is ugly, so activism accomplishes nothing and what’s the pint of fighting? Both versions are defeatist because they are static. What’s missing from these two ways of telling is an ability to recognize a situation in which you are traveling and have not arrived, in which you have cause both to celebrate and to fight, in which the world is always being made and is never finished. (italics mine)

It is because the struggle is never easy and never done that Solnit quotes the poet John Keats, who called the world with all of its suffering “this vale of soul-making.” While “Hope in the Dark” is mainly Solnit’s call to continuous political activism, her arguments apply equally to declaring what’s important to you though the work that you do, that is, to any kind of acting on your convictions. To borrow the force of her argument, your jobs become “toolboxes to change things,” places “to take up residence and live according to your beliefs,” and, as Keats would say, “vales” where your soul is made because it is where a sense of meaning, purpose and wholeness (as opposed to partial victories or defeats) can be found.

If you’re unfamiliar with Rebecca Solnit, “Hope in the Dark”‘s 100-odd pages would be a splendid introduction. Her “A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise In Disaster” such as 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina is a beautiful argument that we’re far more and far better than we often think that we are.

Note: This post was adapted from my September 2, 2018 newsletter

This time it was Charlie Gray who came to our rescue. Once inside, we were packed like sardines, the only “out-of-towners,” and the crowd in front of and behind us started getting rowdy about whether we belonged. “What are you doing here?” “Go back where you came from.” It was already loud in The Crib but our being there took everything up a notch and Charlie noticed.

This time it was Charlie Gray who came to our rescue. Once inside, we were packed like sardines, the only “out-of-towners,” and the crowd in front of and behind us started getting rowdy about whether we belonged. “What are you doing here?” “Go back where you came from.” It was already loud in The Crib but our being there took everything up a notch and Charlie noticed.