There is a difference between new technology we’ve already adopted without thinking it through and new technology that we still have the chance to tame before its harms start overwhelming its benefits.

Think about Google, Facebook, Apple and Amazon with their now essential products and services. We fell in love with their whiz-bang conveniences so quickly that their innovations become a part of our lives before we recognized their downsides. Unfortunately, now that they’ve gotten us hooked, it’s also become our problem (or our struggling regulators’ problem) to manage the harms caused by their products and services.

-For Facebook and Google, those disruptions include surveillance dominated business models that compromise our privacy (and maybe our autonomy) when it comes to our consumer, political and social choices.

-For Apple, it’s the impact of constant smart phone distraction on young people whose brain power and ability to focus are still developing, and on the rest of us who look at our phones more than our partners, children or dogs.

-For these companies (along with Amazon), it’s also been the elimination of competitors, jobs and job-related community benefits without their upholding the other leg of the social contract, which is to give back to the economy they are profiting from by creating new jobs and benefits that can help us sustain flourishing communities.

Since we’ll never relinquish the conveniences these tech companies have brought, we’ll be struggling to limit their associated damages for a very long time. But a distinction is important here.

The problem is not with these innovations but in how we adopted them. Their amazing advantages overwhelmed our ability as consumers to step back and see everything that we were getting into before we got hooked. Put another way, the capitalist imperative to profit quickly from transformative products and services overwhelmed the small number of visionaries who were trying to imagine for the rest of us where all of the alligators were lurking.

That is not the case with the new smart city initiatives that cities around the world have begun to explore.

Burned and chastened, there was a critical mass of caution (as well as outrage) when Google affiliate Sidewalk Labs proposed a smart-city initiative in Toronto. Active and informed guardians of the social contract are actively negotiating with a profit-driven company like Sidewalk Labs to ensure that its innovations will also serve their city’s long- and short-term needs while minimizing the foreseeable harms.

Technology is only as good as the people who are managing it.

For the smart cities of the future, that means engaging everybody who could be benefitted as well as everybody who could be harmed long before these innovations “go live.” A fundamentally different value proposition becomes possible when democracy has enough time to collide with the prospects of powerful, life-changing technologies.

1. Smart Cities are Rational, Efficient and Human

I took a couple of hours off from work this week to visit a small exhibition of new arrivals at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

To the extent that I’ve collected anything over the years, it has been African art and textiles, mostly because locals had been collecting these artifacts for years, interesting and affordable items would come up for sale from time to time, I learned about the traditions behind the wood carvings or bark cloth I was drawn to, and gradually got hooked on their radically different ways of seeing the world.

Some of those perspectives—particularly regarding reduction of familiar, natural forms to abstracted ones—extended into the homespun arts of the American South, particularly in the Mississippi Delta.

A dozen or so years ago, quilts from rural Alabama communities like Gee’s Bend captured the art world’s attention, and my local museum just acquired some of these quilts along with other representational arts that came out of the former slave traditions in the American South. The picture at the top (of Loretta Pettway’s Roman Stripes Variation Quilt) and the others pictures here are from that new collection.

One echo in these quilts to smart cities is how they represent “maps” of their Delta communities, including rooflines, pathways and garden plots as a bird that was flying over, or even God, might see them. There is rationality—often a grid—but also local variation, points of human origination that are integral to their composition. As a uniquely American art form, these works can be read to combine the essential elements of a small community in boldly stylized ways.

In their economy and how they incorporate their creator’s lived experiences, I don’t think that it’s too much of a stretch to say that they capture the essence of community that’s also coming into focus in smart city planning.

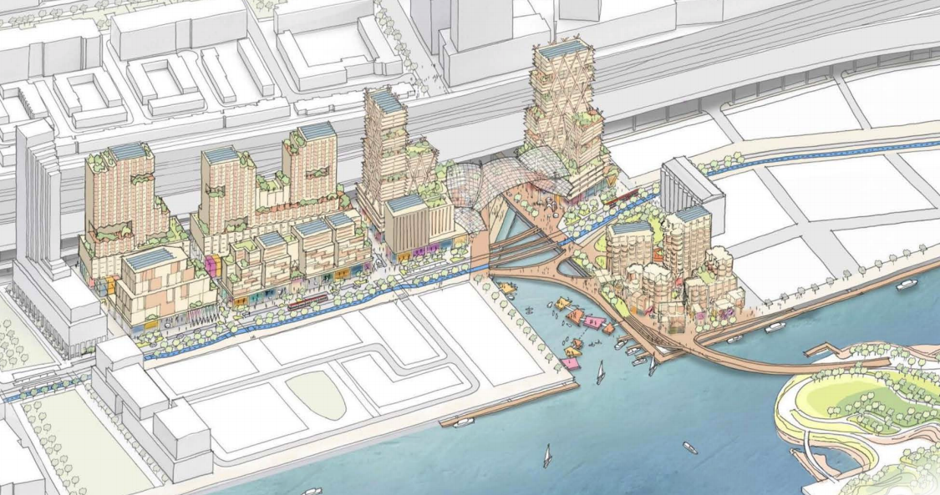

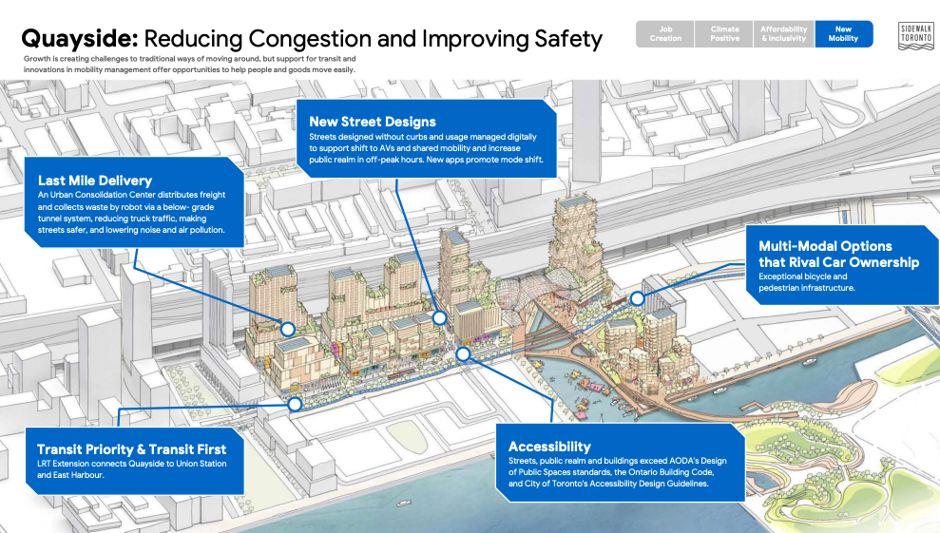

Earlier this year, I wrote about Toronto’s smart city initiative in two posts. The first was Whose Values Will Drive Our Future?–the citizens who will be most affected by smart city technologies or the tech companies that provide them. The second was The Human Purpose Behind Smart Cities. Each applauded Toronto for using cutting edge approaches to reclaim its Quayside neighborhood while also identifying some of the concerns that city leaders and residents will have to bear in mind for a community supported roll-out.

For example, Robert Kitchin flagged seven “dangers” that haunt smart city plans as they’re drawn up and implemented. They are the dangers of taking a one-size-fits-all-cities approach; assuming the initiative is objective and “scientific” instead of biased; believing that complex social problems can be reduced to technology hurdles; having smart city technologies replacing key government functions as “cost savings” or otherwise; creating brittle and hackable tech systems that become impossible to maintain; being victimized as citizens by pervasive “dataveillance”; and reinforcing existing power structures and inequalities instead of improving social conditions.

Google’s Sidewalk Labs (“Sidewalk”) came out with its Master Innovation and Development Plan (“Plan”) for Toronto’s Quayside neighborhood this week. Unfortunately, against a rising crescendo of outrage over tech company surveillance and data privacy over the past 9 months, Sidewalk did a poor job of staying in front of the public relations curve by regularly consulting the community on its intentions. The result has been rising skepticism among Toronto’s leaders and citizens about whether Sidewalk can be trusted to deliver what it promised.

Toronto’s smart cities initiative is managed by an umbrella entity called Waterfront Toronto that was created by the city’s municipal, provincial and national governments. Sidewalk also has a stake in that entity, which has a high-powered board and several advisory boards with community representatives.

Last October one of those board members, Ann Cavoukian, who had recently been Ontario’s information and privacy commissioner, resigned in protest because she came to believe that Sidewalk was reneging on its promise to render all personal data anonymous immediately after it was collected. She worried that Sidewalk’s data collection technologies might identify people’s faces or license plates and potentially be used for corporate profit, despite Sidewalk’s public assurance that it would never market citizen-specific data. Cavoukian felt that leaving anonymity enforcement to a new and vaguely described “data trust” that Sidewald intended to propose was unacceptable and that other“[c]itizens in the area don’t feel that they’ve been consulted appropriately” about how their privacy would be protected either.

This April, a civil liberties coalition sued the three Canadian governments that created Waterfront Toronto over privacy concerns which appeared premature because Sidewalk’s actual Plan had yet to be submitted. When Sidewalk finally did so this week, the governments’ senior representative at Waterfront Toronto publically argued that the Plan goes “beyond the scope of the project initially proposed” by, among other things, including significantly more City property than was originally intended and “demanding” that the City’s existing transit network be extended to Quayside.

Data privacy and surveillance concerns also persisted. A story this week about the Plan announcement and government push-back also included criticism that Sidewalk “is coloring outside the lines” by proposing a governance structure like “the data trust” to moderate privacy issues instead of leaving that issue to Waterfront Toronto’s government stakeholders. While Sidewalk said it welcomed this kind of back and forth, there is no denying that Toronto’s smart city dreams have lost a great deal of luster since they were first floated.

How might things have been different?

While it’s a longer story for another day, some years ago I was project lead on importing liquefied natural gas into Philadelphia’s port, an initiative that promised to bring over $1 billion in new revenues to the city. Unfortunately, while we were finalizing our plans with builders and suppliers, concerns that the Liberty Bell would be taken out by gas explosions (and other community reactions) were inadequately “ventilated,” depriving the project of key political sponsorship and weakening its chances for success. Other factors ultimately doomed this LNG project, but consistently building support for a project that concerned the commmunity certainly contributed. Despite Sidewalk’s having a vaunted community consensus builder in Dan Doctoroff at its helm, Sidewalk (and Google) appear to be fumbling this same ball in Toronto today.

My experience, along with Doctoroff’s and others, go some distance towards proving why profit-oriented companies are singularly ill-suited to take the lead on transformative, community-impacting projects. Why? Because it’s so difficut to justify financially the years of discussions and consensus building that are necessary before an implementation plan can even be drafted. Capitalism is efficient and “economical” but democracy, well, it’s far less so.

Argued another way, if I’d had the time and funding to build a city-wide consensus around how significant new LNG revenues would benefit Philadelphia’s residents before the financial deals for supply, construction and distribution were being struck, there could have been powerful civic support built for the project and the problems that ultimately ended it might never have materialized.

This anecdotal evidence from Toronto and Philadelphia begs some serious questions:

-Should any technology that promises to transform people’s lives in fundamental ways (like smart cities or smart phones) be “held in abeyance” from the marketplace until its impacts can be debated and necessary safeguards put in place?

-Might a mandated “quiet period“ (like that imposed by regulators in the months before public stock offerings) be better than leaving tech companies to bomb us with seductive products that make them richer but many of us poorer because we never had a chance to consider the fall-out from these products beforehand?

-Should the economic model that brings technological innovations with these kinds of impacts to market be fundamentally changed to accommodate advance opportunities for the rest of us to learn what the necessary questions are, ask them and consider the answers we receive?

3. An Unintended but Better Way With Self-Driving Cars

I can’t answer these questions today, but surely they’re worth asking and returning to.

Instead, I’m recalling some of the data that is being accumulated today about self-driving/autonomous car technology so that the impacted communities will have made at least some of their moral and other preferences clear long before this transformative technology has been brought to market and seduced us into dependency upon it. As noted in a post from last November:

One way to help determine what the future should look like and how it should operate is to ask people—lots of them—what they’d like to see and what they’re concerned about…In the so-called Moral Machine Experiment, these researchers asked people around the world for their preferences regarding the moral choices that autonomous cars will be called upon to make so that this new technology can match human values as well as its developer’s profit motives.

For example, if a self-driving car has to choose between hitting one person in its way or another, should it be the 6-year old or the 60-year old? People in different parts of the world would make different choices and it takes sustained investments of time and effort to gather those viewpoints.

If peoples’ moral preferences can be taken into account beforehand, the public might be able to recognize “the human face” in a new technology from the beginning instead of having to attempt damage control once that technology is in use.

Public advocates, like those in Toronto who filed suit in April, and the other Cassandras identifying potential problems also deserve a hearing. Every transformative project’s (or product’s or service’s) dissenters as well as its proponents need opportunities to persuade those who have yet to make up their minds about whether the project is good for them before it’s on the runway or already taken off.

Following their commentary and grappling with their concerns removes some of the dazzle in our [initial] hopes and grounds them more firmly in reality early on.

Unlike the smart city technology that Sidewalk Labs already has for Toronto, it’s only recently become clear that the artificial intelligence systems behind autonomous vehicles are unable to make the kinds of decisions that “take into mind” a community’s moral preferences. In effect, the rush towards implementation of this disruptive technology was stalled by problems with the technology itself. But this kind of pause is the exception not the rule. The rush to market and its associated profits are powerful, making “breathers to become smarter” before product launches like this uncommon.

Once again, we need to consider whether such public ventilation periods should be imposed.

Is there any better way to aim for the community balance between rationality and efficiency on the one hand, human variation and need on the other, that was captured by some visionary artists from the Mississippi delta?

+ + +

Next week, I’m thinking about a follow-up post on smart cities that uses the “seven dangers” discussed above as a springboard for the necessary follow-up questions that Torontonians (along with the rest of us) should be asking and debating now as the tech companies aim to bring us smarter and better cities. In that regard, I’d be grateful for your thoughts on how innovation can advance when democracy gets involved.

This post was adapted from my June 30, 2019 newsletter. When you subscribe, a new newsletter/post will be delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning.