I’ve been re-writing quite a bit since I got back from LA, mostly stories for the book and, in particular, the heart of a central story that I‘d never managed to find before. One of the wonders of “getting away” is the space you reclaim to tackle the problems that were resisting you before you left.

It’s not unlike breaking out of “group-think” by bringing in new energy and perspective to challenge the limitations that were holding you back. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

In thinking about this post, I remembered an observation I’d written down before I left but also didn’t know what to do with. It was made by physicist Geoffrey West in a book he wrote a couple of years back called Scale. Among many extraordinary observations, West noted that one of the reasons cities tend to outperform companies is because cities have more weirdos in them, that is, more people who challenge the prevailing norms or group-think.

Since I’m also still digesting my time in LA, I wondered whether some of the vitality in that city (and maybe in California generally) comes from the fact that there are more contrary voices–more weirdos–participating in the conversation that defines them. After mulling this over for the past couple of days, I’ve concluded that there may be something to it.

A year ago, I wrote two posts: Why Voice Your Dissent? and Dissent That Elevates the Group. In the first, I summarized some of the findings in Charlan Nemeth’s book In Defense of Troublemakers by noting how hard it is to find yourself outside of the mainstream and then to persist, despite your seeming disagreement with everybody else. Summarizing Nemeth’s research, I wrote:

People automatically follow the majority as much as 70% of the time, even when the majority is wrong. People do so because the group ‘works on you’ to conform in blatant as well as subtle ways. Moreover, the remaining 30% are not unscathed by group pressure. In one study, even though the minority disagreed with the group, many reported that the majority was ‘probably correct’ because the group must know something that they didn’t know.

This pull towards conformity is powerful, but there are individual as well as group rewards when dissenters refuse to keep their contrariness to themselves. The courage to persist has three parts:

In addition to your knowledge and experience and what you believe to be true about them, the most productive dissent also contains at least a piece of the future that you are convinced everyone in the group should want. A dissenter’s convictions engage our convictions about what we know and believe, but perhaps neither engage us as much as her hopeful vision about the future we are here to create together.

Cities more than companies listen to its dissenters more, and LA may listen harder than most. It stands on the frontlines of the future because it recognizes the outsized role that its idealists and oddballs have played in getting it there. I also think it’s because dissenting voices are raised less loudly and vindictively on the West Coast than they are on the East. People are more relaxed, or as Emily would say (now that she’s moved there from Brooklyn) they’re way more chill dad. The tenor of LA’s conversation leaves more cooperative energy for when the debate is done. It leaves more space to imagine something better together.

To the hard, gritty realities Los Angelinos confront every day (their tides of homelessness, miles of aging infrastructure, the domination of their cars and roads), they seem to have made room for softness too. They seem to have smoothed the grittier edges but not forgotten them, daring to relax enough to dream with their best dreamers about how to reach a more livable future. They seem to have found ways to remain optimistic in spite of their many challenges. Really, is there any existing option that’s better for the rest of us to follow today?

Here are a few recent experiences in LA that may have caused this question to linger.

1. Grand Central Market

It’s always dicey extrapolating what people are like from their built environments, but how they’ve created new homes and workplaces, shopping centers and entertainment venues (or re-inhabited abandoned ones) always provide clues.

When Emily was younger, we visited the zoo in every place where we traveled. It gave me a lot of anecdotal evidence about how locals thought about wildlife, nature, education, family outings and relaxation. For example, the zoos in London and Barcelona are very different, as you might imagine.

In these and other trips over the years, I’ve also managed to find the central food market wherever am. A benchmark for thinking about these marketplaces has been Reading Terminal Market in my hometown. It may be the most bustling and thriving institution in Philadelphia, regulating the flow of produce, seafood and meat coming in and going out while providing arrays of prepared food in an environment that balances the traditional with the up-to-the-minute. It also looks and feels both effortless and authentic given its time and place.

I could disparage many other cities’ tourist-oriented farmers markets, but I’d rather celebrate LA’s Grand Central Market located in a cavernous old building in the heart of its high-rise downtown. It was where I first started considering the combination of “gritty and soft” in the city.

The cavernous space was dark instead of bright from above. Its inner volumes cascaded down three or four partial levels from one elevation at the Bunker Hill entrance to the Market’s final landing on South Broadway. The building had been hollowed out, with its spine, service lines and ductwork visible, if you looked for them in the dim recesses on walls, ceilings and snaking through lower levels. Inside, it felt like what it was: the shadowy hulk of a re-purposed building.

All of the Market’s establishments—featuring far more prepared food than take-home-and cook—were lit at ground level, glowing like so many individual oases, each inviting exploration while you digested their descending panorama. Food is prepared or assembled in front of you, with seating right there or at tables scattered both inside and out. I made for my recommended breakfast at Egg Slut, whose name and menu perfectly embodied the customer indulgence that seemed to be the goal of every purveyor. Maybe I was too hungry or jet-lagged when I reached the Market, but it seemed like islands of hospitality and surprisingly inventive fare, all of them floating in a multi-tiered, post-industrial space. More friendly and warm than street-level in Blade Runner, but also not unlike it. Gritty and soft.

In succeeding days, I kept detecting this balance. LA is not a beautiful city. Much of it seems yellowed by the sun and little of it has been prettied-up. But everywhere, Los Angelinos seem to have burrowed into their mid-20thcentury sprawl of storefronts and strip malls to create environments that are comfortable, nourishing and full of character. It’s a way that all of us might ride our present into our future if we chose to live within our means while being calmer and less frantic about it.

2. Brunch in Silver Lake

Atmosphere like this invites perspective about what should come next as well as advice for living better right now.

We were at a thoughtfully calibrated outdoor café in Silver Lake when a woman at the next table, who claimed to be 70 but looked 50, volunteered that Emily had beautiful skin and slender, powerful legs. (“I drink water all the time,” Emily said by way of response.) Apparently finding nothing about me to comment on directly, she spent the better part of our meal describing her odyssey as wife, mother, business owner, inventor, personal trainer, author, motivational speaker and yoga instructor and that if she hadn’t changed her life 20 years ago, she wouldn’t be here now. I must have seemed in imminent jeopardy to have aroused her like this.

She then outlined a punishing six-month program of bikram yoga and improved nutrition that made her energetic, hopeful and feeling younger than she had since she was in her twenties. I thought to ask her about her book, whether I could get a motivational tape on-line or see her TED talk but instead I asked her if that was the type of yoga where you sweat your toxins out. Of course it was and based on her apparent diagnosis, of course I said I’d look into it.

This stranger at the next table didn’t complement Emily’s skin and legs because “they looked good” but because of what both of them told her about Emily’s wellbeing. As for me, she didn’t want to sell me anything other than “a choice for me to consider” because taking it had already helped her so much.

LA has been criticized as a shallow and superficial place. I always think of stars or starlets congratulating everyone, thanking God, thanking the orphans of Mogadishu for their award when I hear that. We did see one Academy award-winning actor while we were in a sporting goods store there, but Mahershala Ali is anything but shallow and superficial and neither were most of the locals I met. Admittedly, it was a small random-sample. But those I encountered seemed to have put their health and wellbeing in the present moment closer to the center of their lives and choices than many Americans in other parts of the country.

Being centered like this influences not only how people view the future course of their lives but also the long-term future they tend as custodians for their children and children’s children. When you feel better, get your body and mind under control, there’s more room for optimism and broader responsibility (isn’t there?)

3. The Getty

The Getty Museum sits on heights that overlook Santa Monica Bay and much of the rest of the sprawling city. Locals as well as out-of-towners seemed to dress up to go there. The Persian girls were flamboyant, the Japanese men causally tailored to an extent I’d never seen before and the Japanese women and girls wore complex layers that all seemed part wedding gown and spring raincoat. Everyone at the Getty seemed to understand that they were visiting someplace special to consider treasures from the past. And it was special.

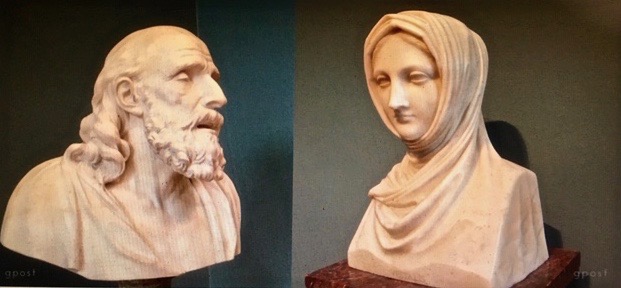

The works of art on display were often as spectacular as the surroundings and visitors. I was particularly dazzled by the collection of marble portrait busts by the West’s greatest carvers, including Bernini and Houdon. Their arrangement was also playful, with curators positioning them so they could interact with nearby paintings or other sculptures. For example, the busts above of Belesarius (a Byzantine general by Jean Baptiste Stouf) and a Vestal virgin (by Antonio Canova) were at opposite corners of a sun-soaked gallery, the goat gazing (longingly and hilariously) into the dove’s eyes.

Like the La Brea Tar Pit Museum chronicled LA’s pre-history (in last week’s post), the Getty seems to serve as a temple to the more recent history of Western art and culture.

It’s where LA says: this is the best of where we have been.

Being at the Getty also reminded me that Philadelphia’s largest foundation (the Pew Charitable Trusts) moved to LA not long ago to support a burgeoning contemporary art scene that has seen major new museums being built (the Broad) and existing ones expanded (LACMA) to celebrate new, experimental artists. LA is championing artistic expression in ways that rival New York, Paris and London.

It’s another way that LA is saying: the future is being envisioned and inhabited here. This is where we are going.

+ + +

The LA I saw offers a perspective that respects the past, striving to live with our history and pre-history and to understand what it is saying to us.

It provides some of the optimism that enables LA to step forward and say to other capitals: we’re not caught in your group-think and grid-lock. Instead, we’re already deciding where we should be going next.

We’re looking back in time for its lessons and encouragements as well as ahead from a center in the present that aims for health and wellbeing.

We’re repurposing our aging, urban sprawl into islands of comfort and hospitality.

We’ve made gritty soft, maybe because we’re more aware than others of what we have left to work with and are simply making the most of it.

Yes, LA was an eye-opener.

This post was adapted from my June 16, 2019 newsletter. When you subscribe, a new newsletter/post will be delivered to your inbox every Sunday morning.