Since writing about Barry Lopez’s new book last week and hearing a lot from you about that post, I couldn’t escape the cry from his heart that we’ll all need to learn more about how to survive as we face the accelerating destruction of the natural world. But then I look outside, where the spring is exploding with life after the rain this morning and it’s hard—no, nearly impossible—to imagine that what I’m seeing has already changed and that I’ll need to get ready for even more troubling changes. Lopez argues that we’ll all need to prepare for life in this increasingly wounded world by learning from people who are already surviving on destruction’s frontlines, even though these battlegrounds are hard for us to see or even comprehend “from our comfortable seats by the swimming pool.” Nevertheless, Lopez invites us to look through his eyes at these “throttled” landscapes and to respond as if they were what we’re seeing around us too.

We need writers like Lopez to help us see what’s coming—like “the before and after” he describes when he travels between a majestic nature reserve, all purples and greens in Western Australia, and the wasted iron-mining sites that border it on three sides. It requires an imaginative leap through his storytelling to mobilize us into living with greater reverence somewhere between these two extremes.

After showing us what we’ve destroyed and continue to destroy—the fragile beauty along with the pain of its loss for those who live there and remember it—Lopez urges on our struggle to strike a new balance before the trade-offs get even worse. It’s his wake-up call from the wilderness. And because first world privilege makes it difficult to accept survival under diminished circumstances, he brings us stories from indigenous communities like the Aboriginal Australians who have learned (over millennia) how to adapt in the aftermath of natural disaster, whether caused by man or by nature itself. When our wisdom is joined with their wisdom, it may be possible for us to imagine new ways of surviving in Earth’s depleted future.

Settling for less. Learning new ways of living from indigenous people. Neither are what we’re accustomed to, particularly when the nature that we see around us lulls us into a false sense of complacency. We need an unusually powerful voice like Lopez’s to counter that complacency before its consequences become even more dire.

Unfortunately, as actively as we’re destroying the planet, we also seem hell-bent on destroying one another.

Understanding a community’s ability to survive in the aftermath of attempts to destroy it also requires an almost impossible leap of the imagination. How can I bridge the gulf between the community I experience around me and those communities struggling to survive the daily “shock wave” of life in Syria and in the ancient communities of western Iraq, or those who have returned to some kind of normal after the “killing fields” of Rwanda, Bosnia and Cambodia? Do the deepening divisions between rich and poor, authoritarian and democratic in the Western world, and the frictions between ethnic communities in much of the rest of it, mean that we have to find ways to bridge this gulf in our imaginations too, before these breakdowns grow even worse? Are diminished returns–and a new kind of survival–the best that we can hope for when it comes to our communities as well?

There are voices today who are crying out from this wilderness too, inviting us:

-to look long and hard into communities around the world that have almost been destroyed so that within our own communities we will hesitate to rip apart what binds us together and become more protective of our fragile connections to one another;

-to consider how political leaders and media outlets can quickly devolve into cheerleaders for murder and even mass murder, enlisting willing executioners from the ranks of the susceptible and the under-employed;

-to learn how communities facing annihilation have not only “come back” but also learned how to co-exist with these same murderers because new political leaders and very old community-building programs have helped them to do so;

-to understand how survivors move beyond grief and despair and can find a level of acceptance (if not forgiveness and reconciliation) after what it happened to them; and ultimately

-to accept that accommodations like this may become our new normal too as the ties that bind our own communities together continue to weaken and fray.

Surviving community destruction has much in common with survival in the wake of environmental destruction. There are voices calling to us from this wilderness too, asking whether the future will be delivered by Enlightenment-based progress–that our global villages will always continue to improve–or that we must instead look to more traditional ways of living to learn how to take care of everyone in a community, refuse to leave anyone behind, and know how to recover when our ties with one another have been broken.

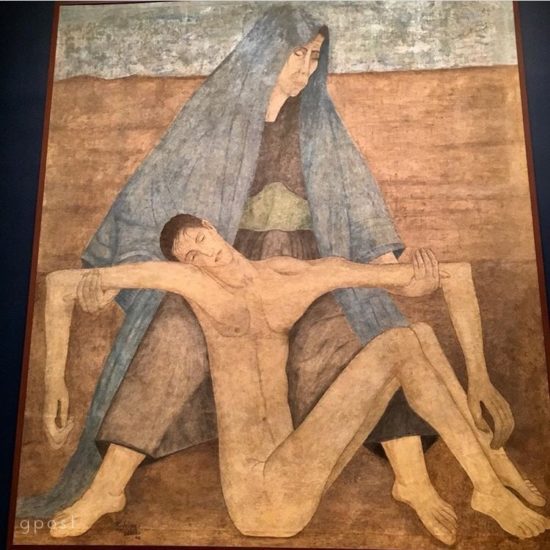

Their message seems timely given the march from destruction to rebuilding that is the seasonal story of winter to spring, brown and dry to lush and green, the death of Good Friday to the life after Easter.

It can be glimpsed in the fresco (above) by Manuel Rodriguez Lozano, painted in a Mexico City prison while he was a political prisoner, its rich symbolism pointing towards his own deliverance.

It is also evident in Philip Gourevitch’s writing about the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, and even more so in how the minority Tutsi tribe that was nearly annihilated by the majority Hutus have built a new future among these same Hutus over the past 25 years.

From this tragedy, many Rwandans (like most survivors) have achieved a quality of being that Finnish people call sisu, a word that has no real equivalent in English. Sisu comes from taking action against the odds and finding courage when it’s difficult to do so. With sisu, you sense that you’re going beyond your capabilities and harnessing inner energy that has never been harnessed before. Something like sisu enables you to move on and not give in to resignation or despair despite the enormity of the challenge.

We’ll all need the endurance of sisu—and other kinds of perspective too—if we’re to survive the destructions of nature and diverse communities that seem inevitable today if we keep our present course.

1. Genocide and its Aftermath in Rwanda

In the spring and early summer of 1994, 800,000 people (mostly Tutsis) were systematically murdered by bands of Hutu génocidaires in what Philip Gourevitch describes a “an unambiguous case” of state-sponsored mass murder. He wrote the book, “We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families” to document the tragedy 25 years ago, and he has been revisiting its consequences ever since.

In a Frontline interview, Gourevich described how the Rwandan government at the time used a pop music station (RTLM or Radio-Television Libre Milles Collines) to rally young Hutus with genocidal propaganda that eventually targeted the resented Tutsi minority with elimination. Over time, it’s directives became shockingly personal.

disc jockeys who would say, “So-and-so has just fled. He is said to be moving down such-and-such street.” And [the genocidaires] would literally hunt an individual who was targeted in the street. And people would listen to this on the radio. It was…a rallying tool that was used… to mobilize the population [into a murderous rage].

The genocide dissipated for several reasons, including an on-going civil war, the involvement of U.N. peacekeepers, and huge numbers of refugees fleeing to camps outside Rwanda. When Gourevich visited the following year:

the country was still pretty well annihilated: blood-sodden and pillaged, with bands of orphans roaming the hills and women who’d been raped squatting in the ruins, its humanity betrayed, its infrastructure trashed, its economy gutted, its government improvised, a garrison state with soldiers everywhere, its court system vitiated, its prisons crammed with murderers, with more murderers still at liberty—hunting survivors and being hunted in turn by revenge killers—and with the routed army and militias of the genocide and a million and a half of their followers camped on the borders, succored by the United Nations refugee agency, and vowing to return and finish the job.

But as he could report just 15 years later in a 2009 New Yorker essay:

Rwanda is [now] one of the safest and the most orderly countries in Africa. Since 1994, per-capita gross domestic product has nearly tripled, even as the population has increased by nearly twenty-five per cent, to more than ten million. There is national health insurance, and a steadily improving education system. Tourism is a boom industry and a strong draw for foreign capital investment.

What accounted for Rwanda’s rise from the ashes? Clearly there were several factors, but one of them was that the Hutus and Tutsis who returned to their lives together had gained a kind of acceptance of their mutual tragedy, and, by doing so, unlocked extraordinary energies that might otherwise have remained buried in grief, despair, revenge or the fear of revenge.

One factor in this turn-around was that a new government vowed to protect all Rwandans and actively promoted local processes that aimed at reconciliation. Paul Kagame, a leader who governed his country with an authoritarian hand through much of this recovery period, was elected in 2003 and immediately repurposed a system of community courts that had previously acted without lawyers to resolve local conflicts called gacaca.

With gacaca, towns and villages would conduct communal, town-hall style trials to hold those who had participated in the genocide accountable and to mete out punishments. Gacaca both encouraged and rewarded confessions, but confessions also had to be verified by other community members. Because the Tutsi and Hutu had usually returned to their homes, people almost always knew one another, the identities of those who had suffered or been killed, and who was likely responsible for the atrocities.

Eventually more than 12,000 gacacas were convened and more than a million cases adjudicated with a remarkable degree of public participation and little violence. Gourevich notes that there “were surely false convictions of those who insisted on their innocence, and …a surprising number of acquittals of those who had probably been falsely accused in the first place. But in many cases…confession was its own reward…[with] sentence[s] for multiple murders reduced to little more than time served.” Gacaca justice, as imperfect as it was, produced a degree of catharsis in their communities and, by allowing these communities to work though the facts and consequences of a shared tragedy, to leave some of its pain, despair and desire for revenge behind. Fifteen years after the genocide, Gourevich:

didn’t see any great hope in the eyes of the people I visited… But as I travelled around Rwanda there was a greater sense of ease among people than I remembered. It wasn’t anything that you’d notice if you hadn’t been there before, because what I was feeling wasn’t so much the presence of strikingly positive energy but, rather, the absence of a mood of wary inwardness. The country was becoming less spooked. At times, it was simply a neutral place to be, like anywhere else. It was normal, which [in itself] was extraordinary.

One of the lessons involved finding this new normal. Gacca courts released the steam from a pressure cooker that could now be reused for rebuilding the country’s injured communities. A remarkable nation-wide recovery in a relatively short-time frame is partly explained by gacca justice. But it was the impact on individual survivors that teaches us the most, a cautionary story with only the faintest traces of hope. In documenting and characterizing what individual Rwandans have said about their recovery, Gourevich shows us how the texture of survival feels when we’ve allowed our communities to be torn apart and are left with no alternative but finding the slow way back.

2. The sisu of survivors

The Rwandans who spoke to Philip Gourevich tell us that community rebuilding from the point of destruction is incomprehensible, cynical, frustrating, taxing, re-traumatizing, but all the while, necessary. For the most part, members of this new community have been unwilling to forgive. Like other kinds of survival, the day in and day out of it is difficult, driven by a tenacious kind of coping instead of the promise of brighter days ahead. The passage of time always erodes pain, but it takes even longer to replace the emptiness with anything that approaches reconciliation.

Here is some of what Gourevich found. The quotes below are from a series of interviews that he gave earlier this month.

-On surviors being re-traumatized: the motto of the gacaca courts was “truth heals,” but the fact is that the truth also wounds all over again. “Every time I come to gacaca with an open mind I get even more upset.”

-On forgiveness: “Pretty much everyone I asked in Rwanda told me the same thing,” Gourevich says. “The most fundamental basis of forgiveness is an internal decision, by the forgiver, to forego revenge—literally to let go of the idea of getting even. I called this modest, a sort of bare minimum, but think about the scale and scope of offenses and injuries we’re talking about, and what it would mean for Rwandans not to forgive [even in this limited sense of the word], and you see it’s no small thing.”

-On the mix of incomprehensibility and necessity in doggedly seeking reconciliation even when you have no hope of finding it:

none of the survivors I spoke with thought that there was any better solution [than gacaca afforded]. Never mind reconciliation, Tutsis and Hutus had to coexist. Sagahutu expressed the sentiment most succinctly: ‘It’s our obligation, and it’s our only way to survive, and I do it every day, and I still can’t comprehend it.’ When I repeated Sagahutu’s formulation to other survivors and to members of Kagame’s Cabinet, it was always met with recognition: Yes, that’s it.

-on accepting the realities and trying to move on from them: There is a kind of “pragmatic civility.” “I know this person did it and am grateful that they’re not denying it anymore.” “We don’t have to be friends, but if we’re not a threat to one another [any longer] then other things can maybe happen.”

-and on how thoroughly Rwanda has attempted to rebuild its communities:

Rwanda’s relentlessness in pursuing genocidaires is unusual. After WWII, some Jews became Nazi hunters and kept at it for the rest of their lives, but they mostly focused on very senior figures. And I don’t know that I’ve ever come across stories or accounts of survivors of the Holocaust who say: I would like to go back, investigate and figure out who did this to my grandfather, who chased him out of his house, who put him on that train, who put him to death, and I want to haul them all into court. It probably wouldn’t be that hard to figure out who those people were in some parts of Germany, but most Jews just said: the hell with it…And of course, now they don’t live where it happened anymore. That’s key. Rwanda is unique, as you say…the most litigated genocide. It’s also the only one where everybody [still] lives intermingled in that way.

In an effort to rebuild its communities, Rwanda has confronted the looming problem that was “both behind and ahead of them” after the genocide in 1994. It’s efforts to find a kind of acceptance about what happened to their country are sobering because sisu makes nearly everyone who embraces it into an adult.

When I listened to Barry Lopez in Philadelphia a week ago, I was struck by how often he described those in the developed West as children (waiting for political saviors, for progress to sweep us along, for technology to solve our problems) instead of as adults who need to rely on ourselves and on one another.

Children also don’t like to be confronted with their own destructiveness, preferring to pretend that they never made a mess of things and therefore that the mess doesn’t exist at all. It’s something like that with the destruction of both nature and our communities today. If I don’t see the evidence of this destruction when I look out my window, it’s not happening, I have not helped to cause it, and I’m hardly responsible for limiting any more of the damage.

Conjurers like Lopez and Gourevich are calling “from the edge” to tell us about the kinds of survival that we can still avoid if we face the on-going destruction and respond to it like adults instead of children.

They’re also telling us that more of humanity’s destructiveness probably lies ahead and something about what our own surviving will look like when that destruction is closer to our doors.

This post was adapted from my April 14, 2019 newsletter. You can subscribe—and receive my newsletter in your in-box every Sunday morning—by providing your email address in the right-hand column.